Nihonbashi district, Great Kanto Earthquake, 1923, looking south toward Kyobashi. In the right far-distance can be seen the dome-capped Dai-ichi Sogo (Insurance) building.

See also:

1923 Great Kanto Earthquake

Post-earthquake Bridge Construction, Tokyo, c. 1932.

Showa Emperor Tours Rebuilt Tokyo, 1930.

Earthquake refugee camp on the Imperial Palace plaza, Tokyo, 1923.

“Newspapers provided recent information on the disaster, and magazines were able to explore issues in more depth, but their poor durability made them less desirable as permanent momentos of the earthquake. Postcards were an accessible commodity through which people could own a material record of the earthquake, and as such were immensely popular.

“… Mitsumura Printing Company, one of only two lithography printers lucky enough to escape damage, made enough from postcard sales to repay all debts and still have plenty of capital for expansion. The popularity of earthquake postcards stemmed from the already established practice of postcard collection.

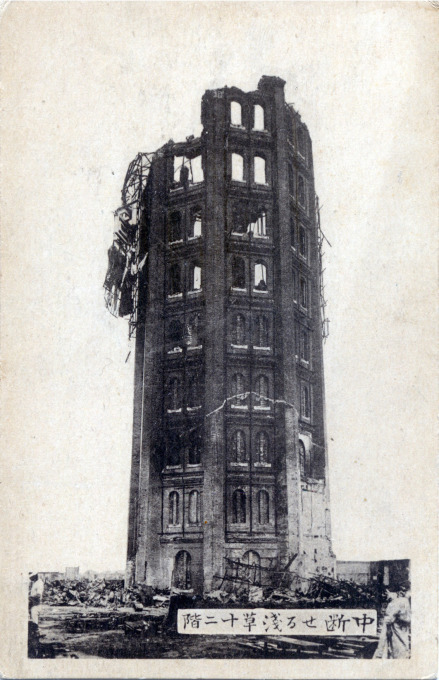

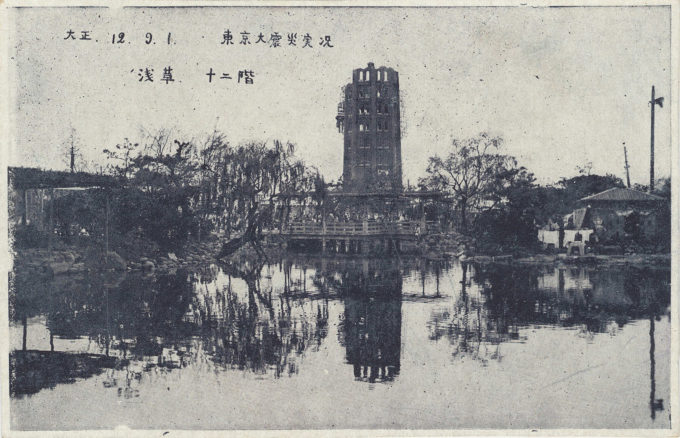

“The Kanto earthquake postcards were part of a larger commercial trend in photojournalistic postcards that began with the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 and continued to cover major events, including natural disasters such as the earthquake in Shiga (1910), the Yoshiwara fire (1912), and the Tokyo floods (1917). Many earthquake postcards focused on the destruction of famous landmarks. The dramatic remains of the twelve-storied Ryounkaku, broken at the eighth floor, were often featured. Others focused on famous districts transformed into burnt wastelands with recognizable landmarks.”

– The Culture of the Quake: The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Taisho Era, by Alex Bates, 2015

- Refugee camp, Imperial Palace plaza, 1923.

- Earthquake refugees in Ueno Park, 1923.

- Great Kanto Earthquake (1923), Nihonbashi.

- Great Kanto Earthquake (1923), Asakusa.

“Photographic images of the Kanto earthquake quickly went from be indexical to iconic through their repeated reproduction and circulation in the mass media, inflecting visual responses in other media such as prints and paintings.

“More than just instruments that mediated between an event and viewership, visual imagery acquired a degree of cultural agency when tropes crystallized and, appearing to take on a life of their own, eclipsed competing portrayals of the disaster.

“In this regard, the photographic eye was profoundly influential in shaping general perceptions of the event, having an impact beyond its memetic capabilities … These visions also communicated the immense and historic scale of the catastrophe that accorded Japan the dubious distinction of premier status in the global theater of earthquake nations.”

– Imaging Disaster: Tokyo and the Visual Culture of Japan’s Great Earthquake of 1923, by Gennifer Weisenfeld, 2012

- “Full view of misery”, Ginza, Tokyo, Great Kanto Earthquake (1923).

- Looking from the Shirokiya department store site at Nihonbashi toward Tokyo Station, 1923.

- Manseibashi Station, after the earthquake, 1923.

- Kanda Ogawamachi, after the Great Kanto earthquake, 1923.