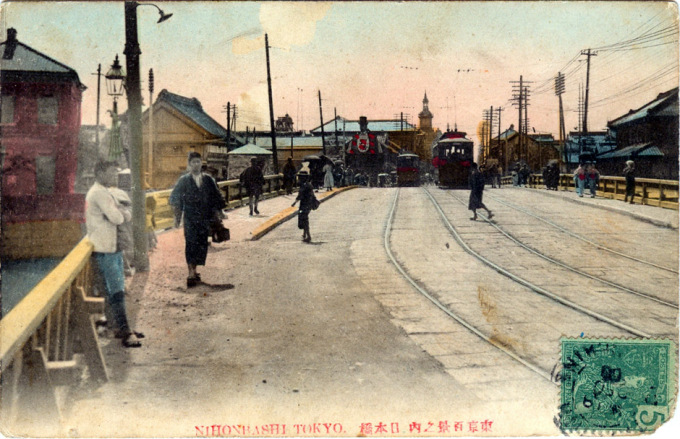

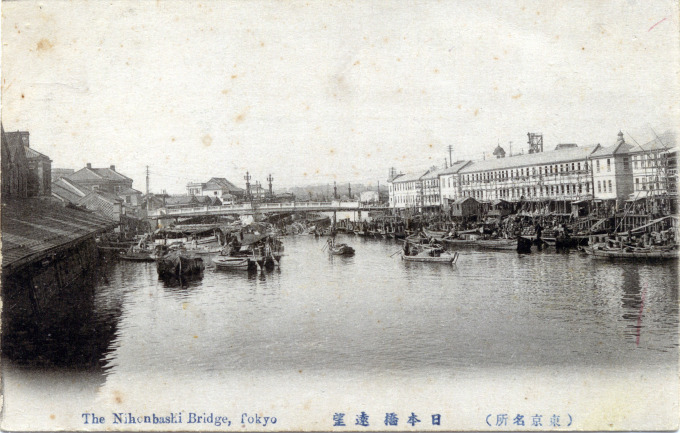

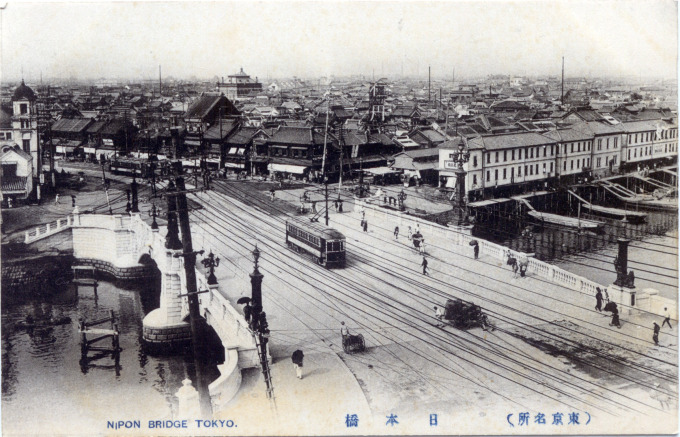

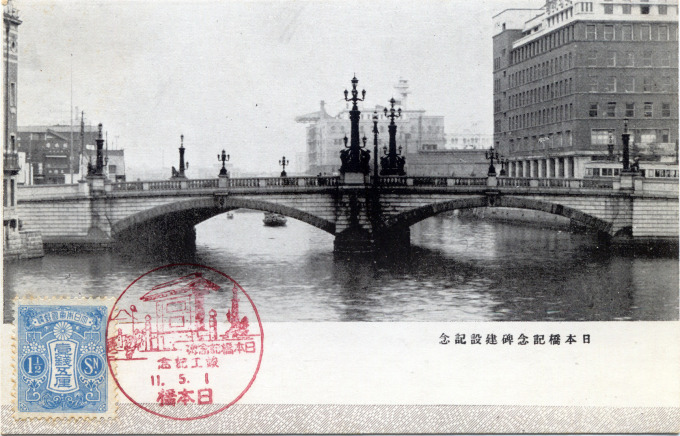

Nihonbashi (sometimes spelled ‘Nihombashi’), c. 1905, an all-wood span erected in 1872 (that replaced a similar Tokugawa-era span dating back to 1603) and which was updated at the turn of the century to accommodate street cars, stood until replaced in 1911 with the more majestic bridge made of stone and brass that still spans the canal today.

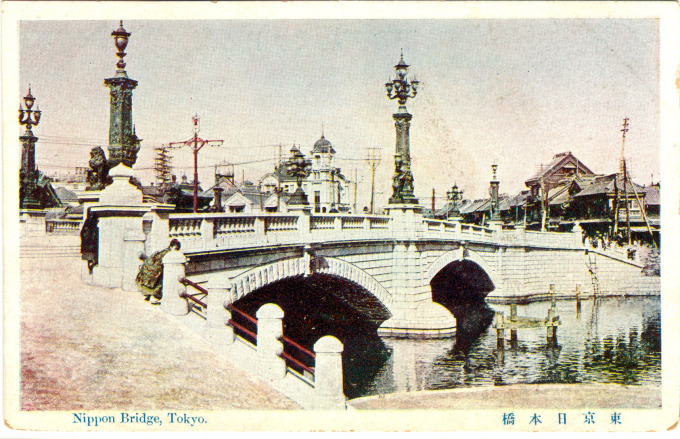

“The creative destruction of modernity was the background to Tekiko’s picture of Nihonbashi Bridge in the print series [‘Woodblock Prints of the Taisho Earthquake’, 1924]. Although the Nihonbashi district had been a flourishing center of Edo commercialism in Tokugawa times, the place Tekiko depicted instead spotlighted the landmark Renaissance-style stone bridge that was built there in 1911 and that still stands today.

“The lion-like sculptures adorning the ends of the bridge are kirin (Chinese-inspired chimerical animals) that were thought to be auspicious. Here, somewhat ironically, surrounded by the debris of the quake, they celebrate Tokyo’s prosperity and symbolize defense of the city. The sculpted figures themselves were symbols of Japan’s modernity, as they were fashioned by artists affiliated with the new Western-style academy, the Tokyo School of Fine Arts [Tokyo Bijutsu Gakko].”

– Imaging Disaster: Tokyo and the Visual Culture of Japan’s Great Earthquake of 1923, by Gennifer Weisenfeld, 2010

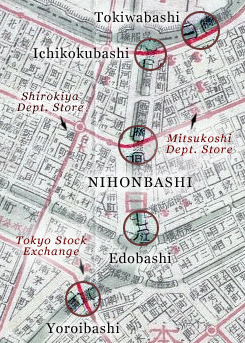

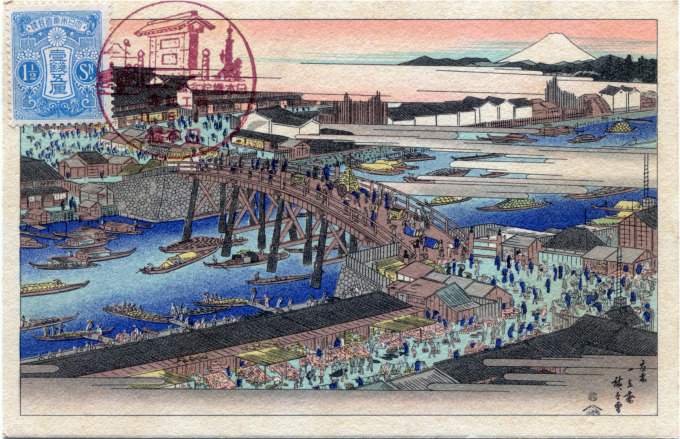

Japan’s most famous bridge, Nihon-bashi [Japan bridge], served two primary roles in feudal Japan: 1) It was the point from which all distances in the country were measured, and 2) the bridge marked the start of the Go-kaido [five town-roads], the five famous post roads – the To-kaido, Koshu-kaido, Nakasendo, Oshu-kaido and Nikko-kaido– connecting Edo, the Shogun’s administrative capital, with the country’s outlying provincial realms and the Imperial capital at Kyoto. (Highway signs of the period noting the distance to Tokyo actually state the number of ri to Nihonbashi.)

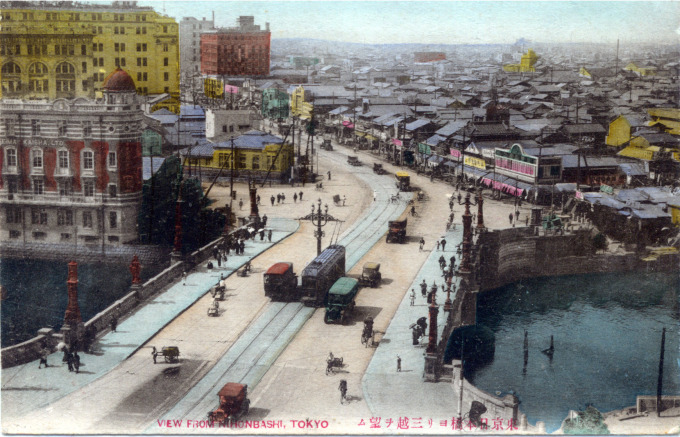

The wooden span erected in 1872 to replace one first erected in 1603 was replaced in 1911 by the larger present-day stone bridge adorned with cast bronze lions.

- Nihonbashi Bridge, c. 1920, looking east..

- Nihonbashi Bridge (left), Imperial Hemp Bldg. (center), Ichikokubashi Bridge (right), c. 1920.

Auspicious kirin sculptures adorn modern Nihonbashi. From a commemorative 25th anniversary postcard set.

- Ukiyo-e reproduction of the Hiroshige woodblock print “Nihonbashi”, from 53 Stations of the Tokaido.

- Nihonbashi Bridge, looking west past canal-side warehouses, c. 1914.

- Nihonbashi, looking north, c. 1914.

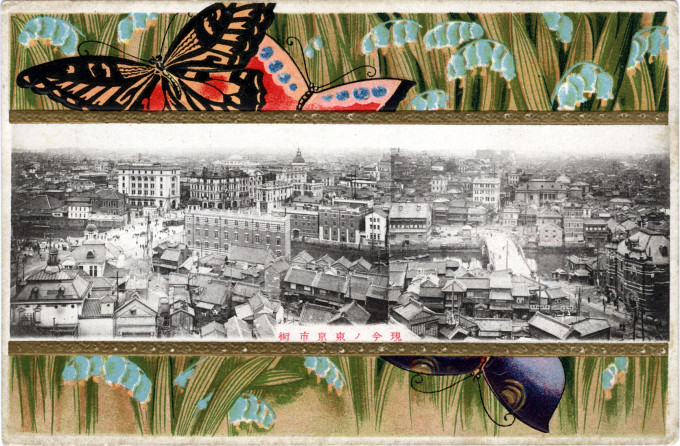

- Nihonbashi, the Imperial Hemp building, and Mitsukoshi department store, c. 1920.

- Nihonbashi, looking north, and the Imperial Hemp building (left) and Mitsukoshi department store (with the tower) in the distance, c. 1920.

- Nihonbashi Bridge tinted elevated view, c. 1930.

The calligraphy cast into the base of Nihonbashi’s two lion-adorned light posts, located mid-bridge, connects the bridge and the district to its feudal origins. The fifteenth, and last, Shogun [general], Tokugawa Yoshinobu, was an accomplished calligrapher and it was decided by the Meiji government to adorn Nihonbashi with his artistic strokes as an act of ritual obligation.

- Commemorative reproduction of Hiroshige Utagawa’s ukiyo-e tri-panel print “True View of Nihonbashi Bridge, Together with a Complete View of the Fish Market” (ca. 1834). (Series: Famous Places in the Eastern Capital.)

- From a commemorative 25th anniversary postcard set.

Now 100 years old, Nihonbashi is still considered first among Japan’s bridges. It is the one of only two surviving Meiji-era spans in the city — the other being the Tokiwa bridge. Nihonbashi today stands obscured and (literally) overshadowed by the elevated Shuto Expressway that follows the old canal.

Pingback: Futagawa, Mikawa, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Horse-drawn trolley, Nihonbashi, Tokyo, c. 1900. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Nihonbashi District. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Yorozuyobashi (Bridge), Tokyo, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Claire Béranger, créations textiles, sculptures » Japon, février 24 (5/ 8) Tokyo 1

Pingback: Claire Béranger, créations textiles, sculptures » Japon, février 24 (5/ 8) Tokyo 1

Pingback: Claire Béranger, créations textiles, sculptures » Japon, février 24 (6/ 8) Tokyo 2