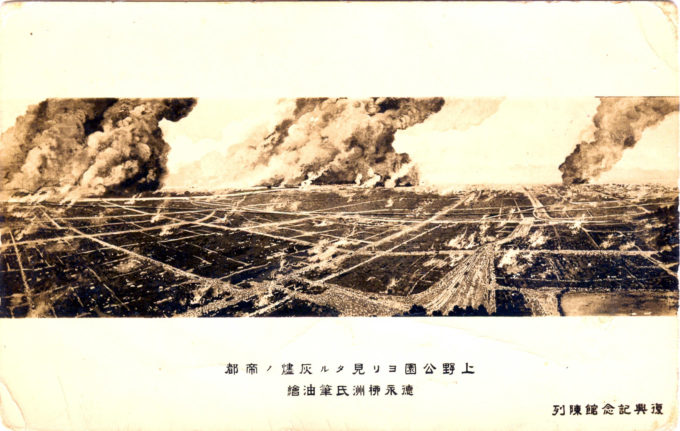

Aerial panoramic view of Tokyo in flames, 1923, looking south from above Ueno Park. Shinobazu Pond and Ueno Hirokoji are seen at lower-right.

See also:

“Earthquake photography”, 1923.

Post-earthquake Bridge Construction, Tokyo, c. 1932.

Earthquake refugee camp on the Imperial Palace plaza, Tokyo, 1923.

Showa Emperor Tours Rebuilt Tokyo, 1930.

“The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 shocked the nation. The magnitude of its destruction was almost beyond imagining. Disaster struck at 11:58 on September 1st, 1923, just as families were gathering around the table for lunch. Most workers went home after a short day at work and for students it was their first day back at school after a long summer break. Although the quake itself measured 7.9 on the Richter scale, the fires that resulted from the overturned cooking stoves in many homes, coupled with high winds caused most of the destruction.

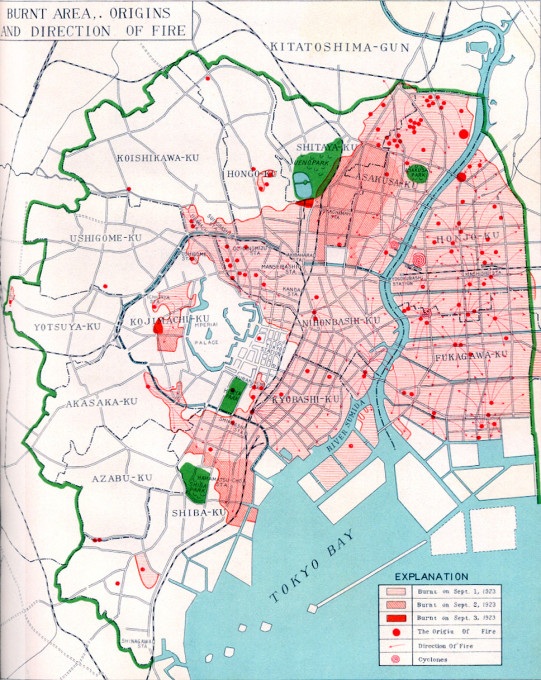

Tokyo, Great Kanto earthquake damage, 1923, illustrating the origins and extent of fire damage. (Source: Tokyo Reconstruction Work, Tokyo Municipal Office, 1930.

“The epicenter of the quake was located near Oshima Island in Sagama Bay (south of Tokyo). The tremors most heavily affected the imperial capital, Tokyo, and left the port metropolis Yokohama in ruins. In total, both the quake and fires that followed claimed the lives of nearly 130,000 people. In Yokohama, 90 percent of all homes were damaged or destroyed while 350,000 homes met the same fate in Tokyo, leaving 60 percent of the city’s population homeless.

“[In the aftermath of the earthquake] in what came to be known as the Korean Massacre, 6,000 Koreans living in Japan and several hundred Chinese and Japanese mistaken for Koreans, were indiscriminately murdered by the Japanese. The massacres were due at least in part to false rumors that the Koreans were planning an uprising. False rumors that the Koreans were: setting fires, poisoning wells, raping and looting, and mobilizing an army first emerged in the Yokohama and Kawasaki areas. When and why did such rumors begin to circulate? It is said that the rumors started mid-afternoon of September 1, spreading across the nation by September 4, reaching even the northernmost island of Hokkaido.”

– The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, Brown University Library Center for Digital Scholarship, 2005

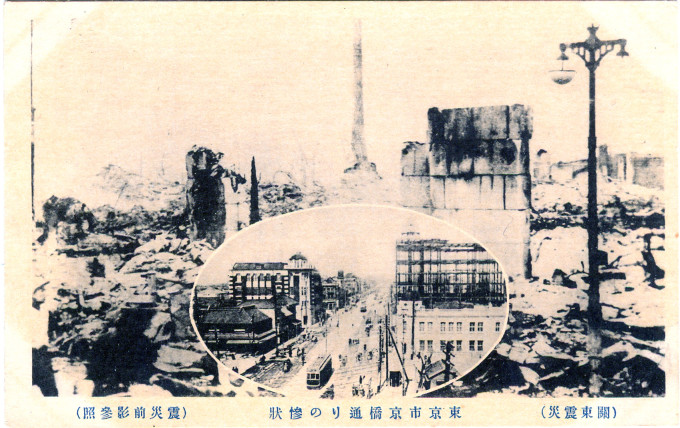

Before & After the Earthquake

- Shimbashi, (Kasumori), c. 1920.

- Shimbashi Station, gutted in the aftermath of the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake.

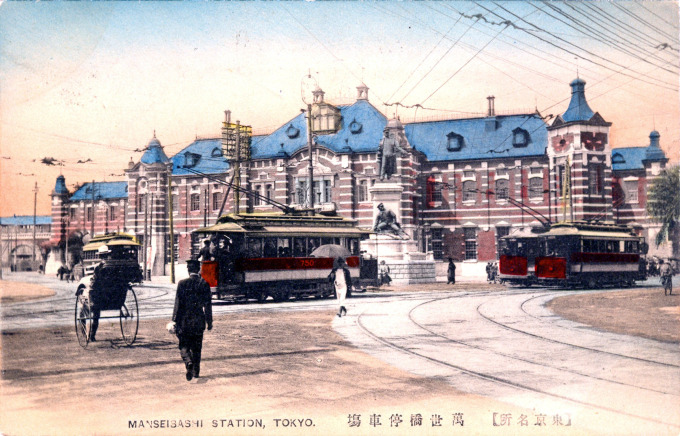

- Manseibashi Station, c. 1910.

- Manseibashi Station, after the earthquake, 1923.

“In the course of three days … Tokyo had become a fire-blackened, rubble-strewn, corpse-filled, stinking wasteland of a once vibrant city.

“Initial comparisons between Tokyo’s catastrophe and the one that had struck San Francisco in April 1906 – the last major urban earthquake disaster on the Pacific Rim of Fire – ended abruptly when the true scale of Japan’s calamity emerged. Fukuda believed that only the war that had ravaged the European continent less than ten years earlier provided an apt comparison with what Japan had recently experienced.”

– The Great Kantō Earthquake and the Chimera of National Reconstruction in Japan, by J. Charles Schencking, 2013

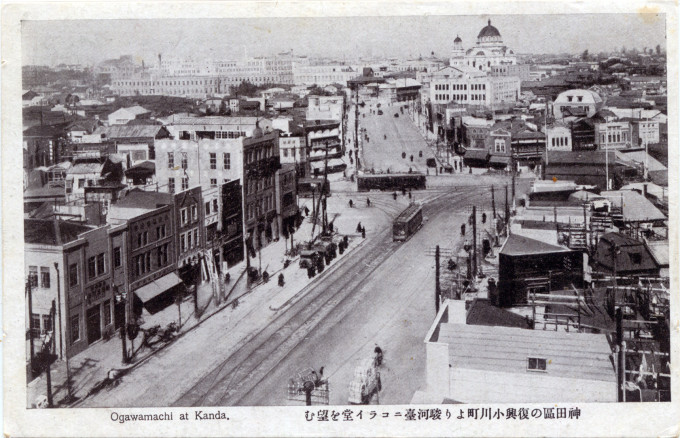

- The Kanda Ogawamachi business district, c. 1920.

- Kanda Ogawamachi, after the Great Kanto earthquake, 1923.

- Dai-ichi Sogo building (right), at Kyobashi, c. 1920.

- Kyobashi, in the aftermath of the Great Kanto earthquake, 1923.

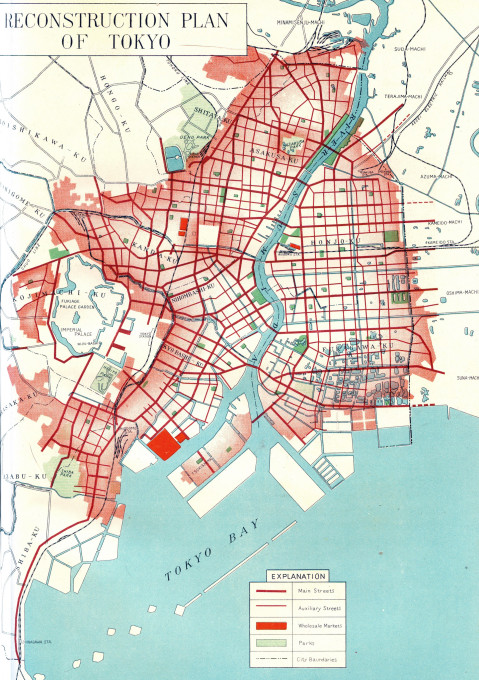

Tokyo Reconstruction Plan in the aftermath of the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake. (Source: Tokyo Reconstruction Work, Tokyo Municipal Office, 1930.)

“Individuals from across the political spectrum, from all class backgrounds, and from a gamut of professions embraced the notion that the civilization-upturning calamity could be manipulated artfully to secure a transformative Taisho restoration. ‘When on earth,’ urban planner Anan Joichi rhetorically asked, ‘will we have another opportunity to construct a modern imperial capital to our heart’s content if we miss this one? Never!’

“Others argued that the social, political, ideological, and economic problems that had manifested themselves with intensity following the First World War – hedonism and decadence, extravagance and luxury-mindedness, flippancy, frivolity, and laxness, political extremism, disunity, social agitation, inflation, and excess – could be not only arrested but also reversed through a project of national renewal.”

– The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Chimera of National Reconstruction in Japan, by J. Charles Schencking, 2013

Pingback: Manseibashi Station (1912-1936). | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Showa Emperor Tours Rebuilt Tokyo, 1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Post-earthquake Bridge Construction, Tokyo, c. 1932. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: "Earthquake photography", 1923. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Earthquake refugee camp on the Imperial Palace plaza, Tokyo, 1923. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo