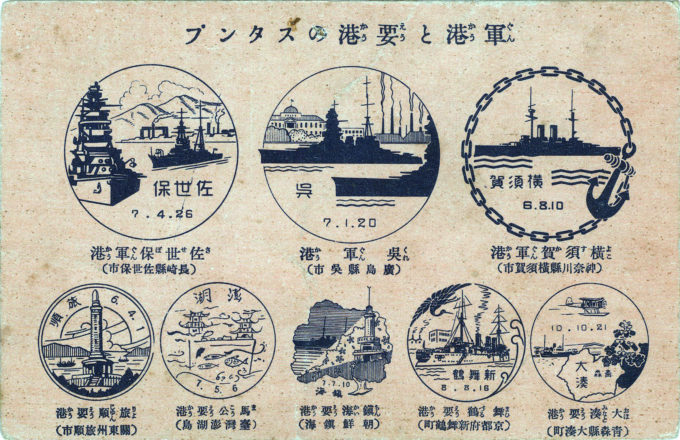

Imperial Japanese Navy bases, c. 1935. Souvenir tourist stamps from the IJN’s Naval Districts and Important Ports within the Empire. See map below. Top row (Naval Districts): Sasebo, Kure, Yokosuka; Bottom row (Important Ports): Ryoujyun (Port Arthur), Makou (Penghu, Pescadores, Taiwan Straits), Chinkai (Jinhae, Korea), Mahizuru/Maizuru (Kyoto), Ohaminato (Ominato, Northern Honshu). The status of Maizuru changed as a result of the 1922 Washington Naval Conference, when it was “demoted” from its original status as a “Naval District” (major naval base) to that of “Important Port”.

See also:

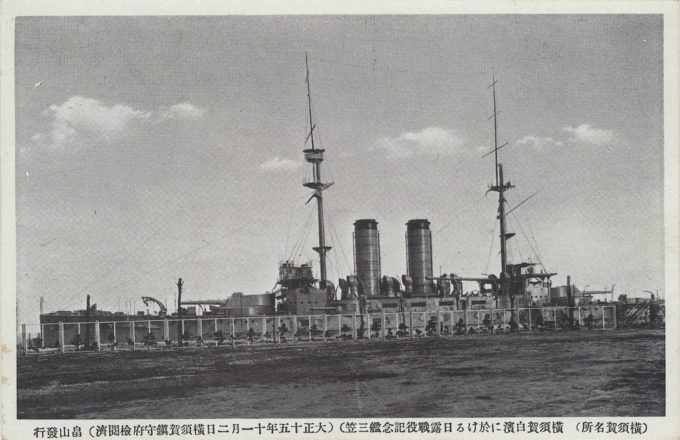

IJN armored cruiser Azuma, c. 1910.

Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, c. 1910.

Kure Kaikokan (Port of Kure), c. 1920.

IJN battleship “Mikasa”, c. 1910.

“Before its rapid urbanization after the establishment of the district base for the Imperial Navy, Shin-Maizuru was a scattered collection of houses along a coastal road. The other three naval cities [Sasebo, Kure, and Yokosuka] also developed from small villages. Unlike cities that grew out of castle towns (jōka machi) or post towns (shukuba machi), Japan’s naval port cities were complete products of modernization.

Map: Imperial Japanese Navy naval districts & bases, c. 1920. The status of Maizuru would be downgraded to ‘Important Port’ following the 1922 Washington Naval Conference.

“… At the 1922 Washington Naval Conference, the major naval powers agreed to reduce armaments. The Imperial Navy duly reduced the scale of Maizuru port drastically, demoting it from the status of district naval base to that of ‘important port’ (yōkōbu) … Fortunately for [city leaders and residents], Maizuru had become a transportation hub by this stage, through which train lines to Kyoto and the Japan Sea intersected. In addition, restrictions that had been strictly enforced while Maizuru was a district navy base were eased, enabling commercial vessels to enter the port.19 With the aim of transforming the shape of the city, leaders, like the navy before them, made the most of Shin-Maizuru’s qualities as an outstanding natural port, and utilized the transportation network that initially had been formed due to the presence of the district naval base.

“The 1923 Shin-Maizuru exposition held between 1 April and 10 May to commemorate the opening of the Japan Sea coastal railway and Shin-Maizuru port provided the city with an opportunity to publicize this new vision of Maizuru. The exposition’s first day was also the day that Maizuru officially changed status to that of ‘important port’. In other words, the exposition marked Maizuru’s shift from a naval to an industrial site. The exposition included approximately sixty-seven thousand exhibits from thirty-two Japanese prefectures, as well as from Korea, Taiwan, South Manchuria, and China. The most popular attractions were naval exhibits and facilities within the navy base that were opened specifically for the occasion. Visitors could observe warships and weaponry in action, board the warship Azuma, ride a large 38-class submarine underwater, and watch a show featuring flying boats and mine detonations. As shown in souvenir postcards, the city used navy-related display pieces to promote the event. From the Meiji period through to prewar Showa, a multitude of different expositions were held all over Japan, but only an erstwhile naval city could stage an event of this type.

“The cruiser Azuma, first deployed during the Russo-Japanese War, was used for practice drills at the time of the exposition. Reflecting tourist interest in warships, the caption describes a ‘group of visitors flooding’ onto the vessel. The postcard is stamped ‘Maizuru Important Port. Commemorating visit to warship Azuma‘, which indicates that it was purchased as a souvenir of its owner’s visit. A postcard with the same commemorative stamp shows the items displayed on the Azuma during the exhibition: a range of artillery shells; the overcoat and short-sword worn by Fujii Kōichi – when he captained the ship during the Russo-Japanese War; a submarine’s weaponry and periscope; and photos of an admiral’s office. Postcards also depict junior high school students on Azuma learning how to operate a warship. Thus, the navy utilized postcards to promote the Azuma as a tourism resource, in order to glorify Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War and train future recruits.

Battleship Mikasa, Yokosuka, c. 1930, an example of a “museum ship”, on display at Yokosuka Naval Yard. The only surviving pre-dreadnaught battleship in the world, Mikasa was decommissioned following the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 and scheduled for destruction. However, at the request of the Japanese government, each of the signatory countries to the treaty agreed that Mikasa could be preserved as a memorial ship with her hull encased in concrete.

“Postcards also depicted the tourist sites of Shin Maizuru. ‘Shin Maizuru fūkei’, an eight-postcard set, which passed navy screening on 10 July 1924, includes photographs of a city modernized through the support of the navy, as well as the images of the naval fleet entering the port (figure 8). Such images demonstrate the unique tourism resources of a naval port city.

“Accompanying naval recruitment efforts, and the industrialization of the city following its demotion to the status of ‘important port’, Shin-Maizuru, a city of little immediate tourist appeal, began to attract tourists through its port, weaponry, and status as a naval city. Promotional postcards were produced at least until 1939, when Maizuru regained its status as district naval base, and these demonstrate inter-linkages between the navy, the naval city, and tourism.

“After the war, Maizuru port and facilities were repurposed for the repatriation of Japanese returning from the former empire and battlefields. Initially, several ports served this role, but these were reduced as the number of returnees decreased. Maizuru — well-situated for the many Japanese returning from internment in Siberia — remained a port of reentry for thirteen years following the war. From 1950 to 1958, it was the sole port of repatriation. During this thirteen-year period, 346 ships carrying a total of 655,583 repatriates entered Maizuru port.”

– “Selling the Naval Ports: Modern-Day Maizuru and Tourism”, by Uesugi Kazuhiro, Japan Review: Journal of the International

Research Center for Japanese Studies, Vol. 33, 2019