Early victories of the Great East Asia War, cover wrap for a propaganda postcard series, c. 1942. Black “bomb” markings note the sites of Imperial Army air force and Imperial Navy carrier and submarine attacks; black “ship” markings locate Imperial Navy victories; red and white hinomaru flags mark territories successfully captured in the early months of the Pacific War.

See also:

“Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” propaganda postcard, 1942.

“Do not forget”, Imperial Rescript for the Declaration of War, propaganda postcard, c. 1942.

Attack on Pearl Harbor propaganda postcard, c. 1942.

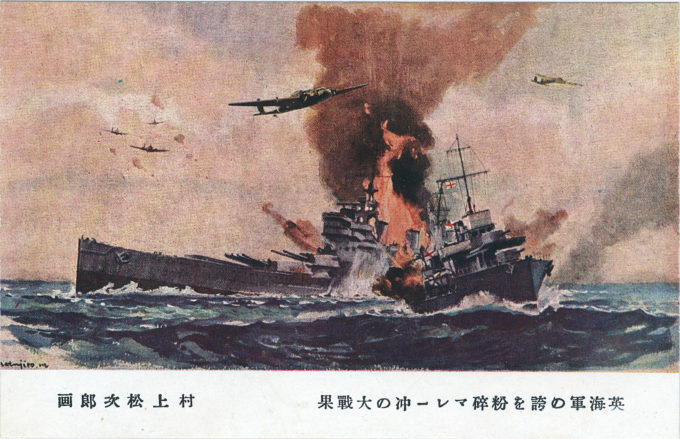

Sinking the HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse propaganda postcard, 1941.

The Battle of Wong Nai Chung Gap (Hong Kong) propaganda postcard, 1942.

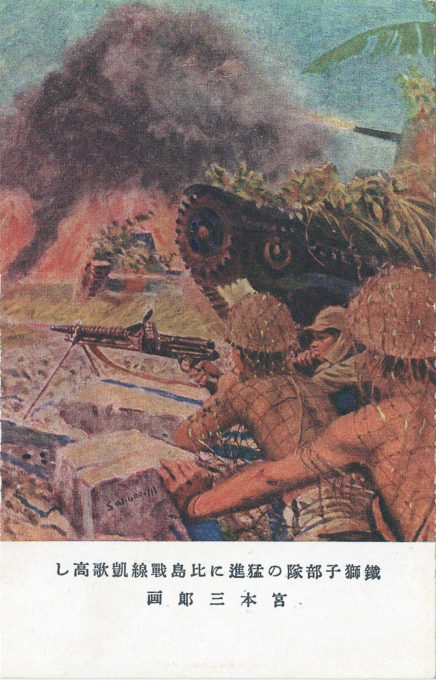

“Imperial marine paratroopers at the Battle of Manado”, propaganda postcard, 1942.

The Surrender of Singapore, 1942.

Indian Ocean raid (“Operation C”), Imperial Japanese Navy, 1942.

“Japan during the 1920s and 1930s pursued a plan that was intended to leave her in complete control of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

“She pursued an expansionary diplomtatic course that would allow her to leverage her limited natural resources to gain the greatest overall advantages withpolitical and military dominance of the Far East as the ultimate reward.

“Knowing she would compete with nations far larger and stronger than herself, Japan seized opportunities for relatively painless expansion at the West’s expense as these opportunities arose. She picked up the pieces of Germany’s lost Pacific Empire, negotiated positional and military advantages with the great Western powers, and developed naval theories that fit the new and evolving Pacific power structure.

“… The legendary raid on the American naval bastion of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, was not a spur of the moment plan. Indeed, it was the outgrowth of the Japanese naval doctrine that had roots going back to the Sino-Japanese of 1894-1895. This doctrine stated, ‘Strike the enemy on the fringes with cheap craft, capable of quick and easy replacement’ – a classic definition of aerial ‘blitzkrieg’.

“… There is no doubt the attack succeeded in its primary mission. The purpose of the Hawaiian operation had been to prevent the U.S. fleet from meddling in the invasion of the Dutch East Indies and Malaya, and it definitely succeeded in this mission … After the attack on the American naval base, the U.S. Navy was unable to advance substatial naval reinforcements into the Western Pacific to affect the desperate fighting there.

“Indeed, for a period of time, after the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor, the Pacific Fleet retired to the West Coast of the United States. The way was open for Japan to pursue its long-cherished dream of advancing into the South Seas.”

– Violet Lightning: A Blueprint for Japanese Victory in the Pacific: 1941-1942, by John Eric Vining, 2020

- “Attack on Pearl Harbor”, Hawaii (U.S.), propaganda postcard, 1942.

- “HMS Repulse and destroyer escort under attack”, propaganda postcard, c. 1942.

- “Army Paratroopers in Action”, Battle of Manado propaganda postcard, 1942.

- “Battle of Surabaya Sea”, Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), propaganda postcard, 1942.

“After the raid on Pearl Harbor, Japan gained more freedom to move south toward the ultimate goals of her expansionist policies – Malaya and the Dutch East Indies – without interference from the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Yet there were other obstacles in her path that had to be considered. The first was the disposition of a U.S. possession directly east of Japan’s route to the south – the Philippine islands.

“The conquest of the Philippines was considered necessary to reduce a major enemy bastion directly on the left flank of the planned move south. Although isolated, the U.S. offensive power in the Philippines (embodied in the long-range B-17 heavy bombers) represented a significant risk to Japanese operations in the South China Sea and the constricted Formosa and Luzon Straits.

“… Although major American forces remained intact in the Philippines until May 1942, the outcome of the battle was hardly in doubt after the initial crippling air raid [against the American Far East Air Force] of December 7, 1941. The Philippines fell, and the Japanese eliminated the danger to the left flank of their southward expansion.

“The Southeast Asia Campaign was actually composed of four operations. The first phase was was a navy-dominated operation to protect [Japan’s] invasion fleet bound for Southern Malaya …[and] to neutralize the British battle fleet based in Singapore, whose main strength was embodied in the battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse.

“… On December 10, Japanese reconnaissance planes reported the British fleet had vacated Singapore. The British commander, Sir Tom Phillips, was under the impression that was sailing out of range of Japanese land-based air power. The British Fleet cruised toward the Malayan invasion force with no air umbrella. The ships were quickly spotted by long-range reconnaissance planes, and the Japanese dispatched ninety-five Betty and Nell bombers … The Repulse, struck by 18 torpedoes and one bomb, sank at 2:20 p.m. The Prince of Wales suffered hits from 2 bombs and 8 torpedoes and sank ten minutes later.

“… The second phase of the Malayan campaign was the air and land battle over and on the Malayan peninsula itself.”

– Violet Lightning: A Blueprint for Japanese Victory in the Pacific: 1941-1942, by John Eric Vining, 2020

“Paratroopers attack Palembang oil refinery”, Sumatra, Dutch East Indies, propaganda postcard, 1942.

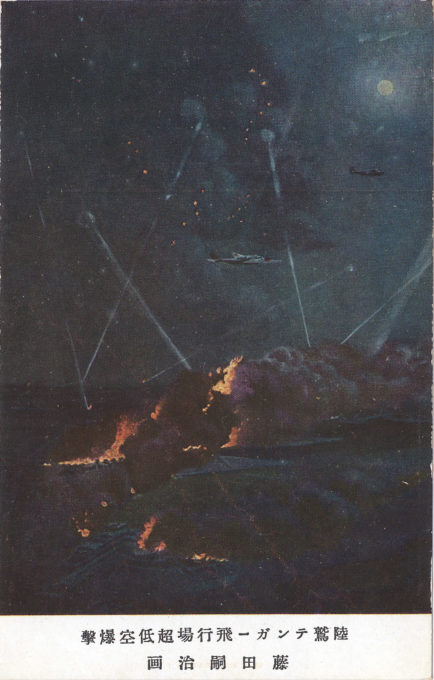

- Tengah Airfield (Singapore) Low Altitude Bombing propaganda postcard, 1942.

- Battle of Hishima, Philippines, propaganda postcard, 1942.