“The dispatch of British capital ships to Singapore had been part of the Admiralty’s strategic planning since the naval base had been expanded and fortified beginning in the early 1920s. The scale of this planned deployment had been reduced during the 1930s, since Germany and Italy presented new threats to British interests in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. Nevertheless, it was still assumed that a significant force of capital ships would deter Japanese expansion. Churchill’s plan presumed that the United States would agree to send its Pacific Fleet, including eight battleships, to Singapore in the event of hostilities with Japan [which, as the result of the Pearl Harbor attack, became an impossibility], or that the British force would add to the deterrent value of the US fleet, should it stay at Pearl Harbor.

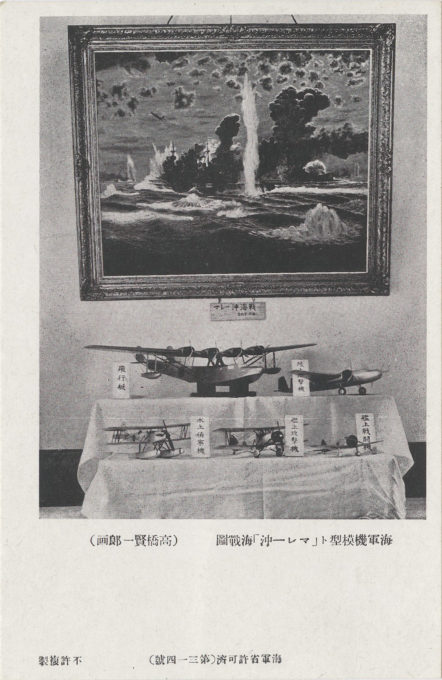

A display of the aircraft types participating in the sinking of the Prince of Wales and Repulse in December, 1941. Top row: Kawanishi H6K flying boat, Mitsubishi G3M medium-range bomber. [The more modern G4M was also used.] Bottom row: Aichi E13A seaplane, Yokosuka B4Y torpedo bomber, Nakajima Ki-27 fighter plane.

“The objective of Force Z, which consisted of one battleship, one battlecruiser and four destroyers, was to intercept the Japanese invasion fleet in the South China Sea north of Malaya. The task force sailed without air support. Although the British had a close encounter with Japanese heavy surface units, the force failed to find and destroy the main convoy. On their return to Singapore they were attacked in open waters and sunk by long-range torpedo bombers. The commander of Force Z, Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, elected to maintain radio silence and an alert was only sent (by the Repulse) one hour after first Japanese attack.

“After Winston Churchill publicly announced Prince of Wales and Repulse were being sent to Singapore to deter the Japanese. In response, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto … reinforced the existing Kanoya Air Group and Genzan Air Group [in Thailand], whose pilots began training for an attack on the two capital ships.

“… [The] Japanese were jubilant. ‘No greater victory than this will be won,’ enthused Admiral Ugaki Matome, the Chief of Staff of Combined Fleet, as he pondered what to call the battle … As for Yamamoto himself, one of the Combined Fleet staff officers recorded his reaction: ‘The Admiral was smiling, with both cheeks flushed. For the first time I saw a bright smile on his face, which usually was almost expressionless.’ He had bet ten dozen bottles of beer that both British ships would be sunk.

“The ‘Battle Off the Malay Coast’, as the Japanese quickly named the sinking of Force ‘Z’, was more important than [the attack on] Pearl Harbor. It extinguished British sea power in the Far East and it was the precise moment in the history of warfare where air power overtook the battleship.

“Admiral Phillips made some poor decisions, but the British were also unlucky. Had Prince of Wales and Repulse arrived in Singapore a couple of weeks earlier, or a couple of weeks later, they might have avoided their fate. Phillips had the misfortune to arrive as war broke out. The defeat, ultimately, was the result of poor British intelligence, a fatal underestimation of the Japanese, and a failure to coordinate the operations of the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force.

“… ‘In all the war I never received a more direct shock,’ Churchill wrote in his memoirs. ‘As I turned over and twisted in bed the full horror of the news sank upon me … We everywhere were weak and naked.'”

– December 1941: Twelve Days that Began a World War, by Evan Mawdsley, 2011

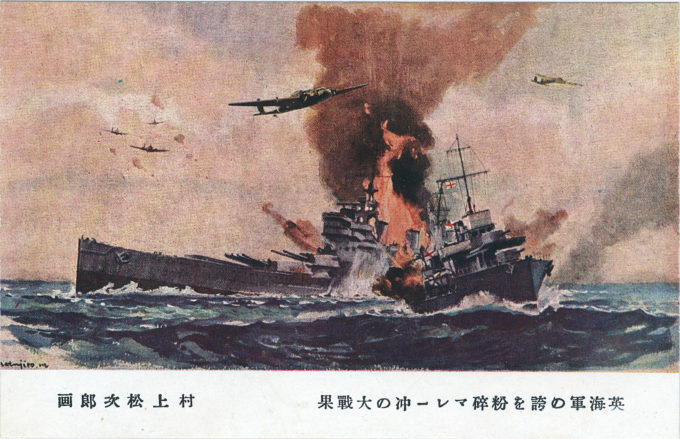

Sinking the HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse propaganda postcard, 1941.

1940s • Historic Events • Patriotism/Military

Tagged with: Aircraft, Imperial Japanese Army, Imperial Japanese Navy, Kawanishi aircraft, Mitsubishi aircraft, Nakajima aircraft, Propaganda, Singapore, Southeast Asia, World War II, Yamamoto Isoroku (Admiral)

Please support this site. Consider clicking an ad from time to time. Thank you!