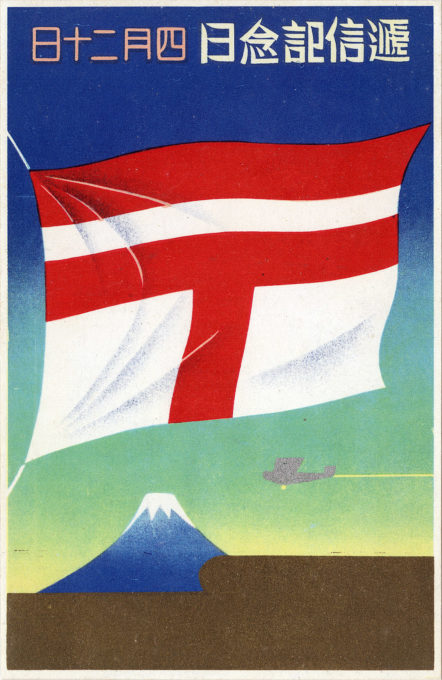

“Communications Day” commemorative postcards, 1937. The day was inaugurated in 1934 to celebrate the founding of the modern Japanese Postal Service on April 20, 1871. (Since 1950, the day has been known as Post Office Day.)

See also:

Teishin-sho (Ministry of Communications), Tsukiji, c. 1900.

Japan Postal Service 50th Anniversary commemorative postcard, 1921.

50th Anniversary of Japan’s entry into the Universal Postal Union commemorative postcard, 1927.

Japan’s first modern postal service got underway in April 1871, with mail professionally traveling between Kyoto, Osaka and Tokyo. Prior to that, Western nations maintained foreign post offices in the major ports as an extraterritorial right. After the formation by Baron Maejima Hisoka of a modern postal system, the treaty right under which the foreign post offices operated was renegotiated, resulting in the first cancellation of any ‘unequal treaty’ between Japan and the Western powers.

Maejima’s postal service began with 65 post offices between Tokyo and Osaka. When he left office in 1881, there were 5,900 post offices throughout the country. Maejima also took the lead in organizing postal savings and money order systems, revising weights and measures, and would, later in life, found Tokyo Senmon Gakko (renamed Waseda University in 1901) and served as its second president (1886-1890).

“Communications Day” commemorative postcards, 1937, illustrating the various means at the time of domestic and international postal transport and delivery, from bicycle to airplane and radio telegraphy.

On December 22, 1885 the Ministry of Communications was established, combining the Bureau of Posts and Post Station Maintenance and Shipping Bureau formerly under the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce with the Telegraph Bureau and Lighthouse Management Bureau formerly under the Ministry of Industry. On August 16, 1891, the ministry was also placed in charge of the nascent Japanese electric power industry. On July 21, 1892, the Railway Bureau was transferred to the Ministry of Communications from the Home Ministry (later separated into its own cabinet-level bureau in 1908 upon the nationalization of private railways). In April 1923, responsibility for civil aviation supervision was transferred to the ministry from the Army Ministry.

After the surrender of Japan in 1945, the American occupation authorities briefly reestablished the Ministry of Communications on April 1, 1946; however it was in charge of only posts, telecommunications and the security of aerial navigation. The Ministry was formally abolished on April 1, 1949 and its responsibilities divided between the new Ministry of Postal Services and Ministry of Telecommunications.

“Communications Day” commemorative postcards, 1937. The Lighthouse Management Bureau fell within the purview of the Ministry of Communications beginning in 1885.

“Japan’s postal service owes an incalculable debt to Samuel Magill Bryan. He created her international postal service. Moreover, he negotiated Japan’s first ‘equal treaty’ with another country.

“… In 1869, again with Congressman [John A.] Bingham’s assistance, young Bryan obtained a fortuitous position. He was transferred to the Sixth Auditor’s Office in the Treasury Department. This agency audited the financial records of the Post Office Department and was housed in the Post Office Department building. Bryan’s salary was $1,400 annually. Specifically he audited the accounts of mail exchange between the United States and Great Britain. There he gained much knowledge about the international mail service which would be of great help in his future plans.

“… On February 29, 1872, a special embassy to America and Europe arrived in Washington, D.C. Consisting of Japan’s most influential leaders and led by Prince Tomomi Iwakura, it aimed to solicit revision of treaties imposed on Japan by the powers. It was escorted by Charles E. DeLong, U.S. Minister Resident to Japan. Bryan immediately became interested in the Japanese delegation and DeLong because, having learned that the Japanese government was employing foreign advisors in various fields at excellent salaries, he determined to seek one of those positions.

“… [A]s a U.S. Treasury Department auditor of the British mail accounts, Bryan had an opportunity to acquire a broader and more detailed understanding of the foreign mail service than many clerks actually on the Post Office Department staff. Moreover, he came to Japan armed with current and historical statistics on the American postal service, and in Japan he obtained more data — concerning the revenue and expenses of the British, French, and American post offices in Japan. The latter information was not available to the Japanese government, and Bryan no doubt obtained it through Charles DeLong.

“To support his application for appointment as chief of a still-to-be-created foreign mail section of the new Japanese postal service, Bryan submitted a proposal based on statistics of the British, French, and American post offices in Japan. By his reckoning, Japan could created its own foreign mail service, employ him at an annual salary of $4,800 (four times what he had been paid in Washington), hire four other foreigners to assist him at an additional cost of $10,000 a year, and still make an annual profit of $47,299.

“Maejima concluded that Bryan’s postal knowledge could be the key to his dream of abolishing the foreign post offices in Japan … [O]n February 14, 1873, [Maejima] gave him a three-year contract to negotiate postal treaties not only with the United States, but also with Britain, France, and Germany. His starting salary was $5,400 a year ($600 more than he had originally asked for).

“… On February 24, 1873, Bryan left Yokohama for Washington to negotiate the postal treaty. On August 6, 1873, the treaty was signed. This was the first treaty in which a Western nation treated Japan like an equal. Also it was the first treaty in which a Western nation agreed to relinquish one of the privileges of extraterritoriality in Japan. Moreover, it was a treaty wherein Japan gained preferential treatment. It required the United States to close all American post offices in Japan, nothing being required in return.

“… The American-Japanese treaty had important ramifications. It convinced many Japanese officials that the U.S. was the friendliest of nations with which it was bound … Furthermore, the treaty led to a Japanese foreign mail service which, under Bryan’s leadership, quickly proved to be more efficient than the limited American service it replaced.”

– “Samuel Magill Bryan: Creator of Japan’s International Postal Service”, by Erving E. Beauregard, Journal of Asian History, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1992)