“Perry’s seven-ship fleet entered Shimoda harbor. As the shogunate limited Japanese vessels to a maximum displacement of around 100 tons, these enormous metal steamships — Perry’s flagship, the Powhattan, was 2,415 tons — appeared as menacing, three-masted hulks to the townsfolk, belching smoke from their funnels and bearing cannons that boasted formidable firepower.

“On April 21, Perry and a few men stepped ashore, the first foreigners to set foot in Shimoda. They were received by a Japanese delegation at Ryosenji Temple.

“The Shimoda Treaty was signed on June 20, 1854, its 13 articles supplementing the Kanagawa Treaty. The new treaty allowed Americans free movement within a 28-km. radius of Shimoda, established a procedure for trade in basic supplies, and designated Ryosenji and Gyokusenji as a resting place for American officials, with the latter temple also providing a last resting place for deceased foreigners.

“Neither of the 1854 treaties established formal trade relations between the two nations. However, in 1856, Townsend Harris, the first American consul in Japan, took up lodging at Gyokusenji and pressed the shogunate to open the country to commercial exchange. Eventually, he succeeded, and the Harris Treaty was signed in 1858.”

– “Shimoda Black Ships Festival: A special weekend in Izu to remember and enjoy”, by Alex Zabusky, The Japan Times, May 14, 2004

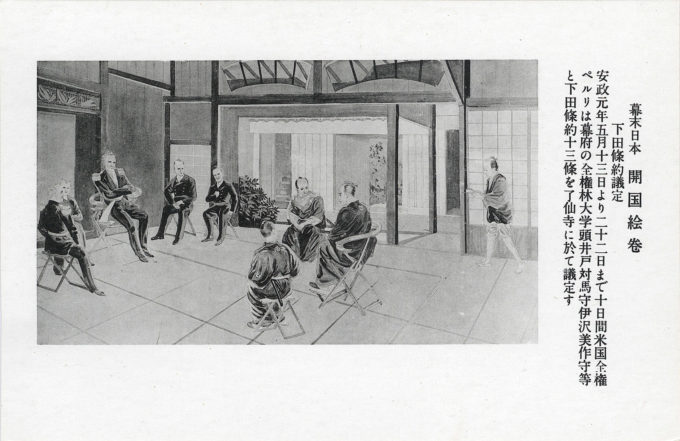

Commodore Perry negotiating at Ryosenji Temple in 1854, Shimoda, commemorative postcard, c. 1930. The caption reads: “In the first year of the Ansei Era [1854], for ten days from May 13 to May 22, the U.S. government’s supreme authority was exercised at Ryosenji temple in Shimoda concerning the 13 articles of the Shimoda Treaty.” The articles of the Shimoda Treaty further supplemented the terms of the Kanagawa Treaty (officially the “Japan–US Treaty of Peace and Amity”) agreed to two months prior, in March 1854, which ended Japan’s self-imposed policy of national seclusion. The Treaty of Shimoda stipulated details for the usage of Shimoda port by Americans, who were now officially allowed to walk freely in Shimoda and officially allowed to communicate with Japanese commoners for the first time in Japanese history. Ryosenji is now memorialized as “the Hall of Opening the Nation.”

See also:

Matthew C. Perry Landing Memorial, Kurihama, c. 1949.

“There are no less than nine Buddhist temples, one large Mia, or Sintoo temple, and a great number of smaller shrines. Those devoted to the worship of Buddha have strange fanciful titles: the largest is called Rio-shen-zhi, or Buddha’s obedient monastery; and there are the Dai-an-zhi, or great peace monastery; the Hon-gaku-zhi, or source of knowledge monastery; the Too-den-zhi, or rice field monastery; the Fuku zhen-zhi, or fountain of happiness monastery; the Chio-raku-zhi, or continual joy monastery; the Ri gen-zhi, or source of reason monastery; and lastly, the Chio-me-zhi, or long life monastery.

“The nine Buddhist temples are all situated in the suburbs, back of the town; and on the acclivities or summits of the hills, which bound them in the rear, there are shrines and pavilions erected within groves of trees, which are approached by flights of stone steps. In the interior of these pavilions and shrines are rude images, or merely inscriptions, dedicated to the tutelary deities of the spot.

“Their purpose is to afford facility to those living near, or to the passer by, of appeasing and imploring the good and evil spirits which are supposed to visit the neighborhood. At the door and before the shrines there are always bits of paper, some rags, copper cash, bouquets of flowers, and other articles, which have been placed there as propitiatory offerings by the different devotees.

“The Rio-shen-zhi , the largest of the nine Buddhist temples, was set apart by the government authorities for the temporary use of the [Americans] during the stay of the squadron. It is situated on the south side of the town, and has quite a picturesque aspect, with a precipitous rock of over a hundred feet on one side, and a burial ground on the other, extending up the acclivity of a thickly wooded hill. Connected with the temple is a kitchen garden, which supplies the priests with vegetables, and pleasure-grounds with beds of flowers, tanks containing gold-fish, and various plants and trees.

“A small bridge, neatly constructed, leads from the gardens to a flight of steps, by which the hill in the rear is ascended. Adjoining the ecclesiastical part of the establishment there is a hall used for lodgers, which is so constructed with sliding doors, that it may be separated into several rooms for the accommodation of many persons, or left as one apartment.

“The officers of the squadron were comfortably provided for here, and with an abundant supply of mats to sleep upon, good wholesome rice and vegetables to eat, plenty of attendants, and everything clean, there was very little reason for complaint on the score of the material necessities of life.”

– The Americans in Japan: An Abridgement of the Government Narrative of the U. S. Expedition to Japan under Commodore Perry, by Robert Tomes, 1857

Pingback: Commodore Perry and the “Expedition to Japan” (1853) souvenir postcards, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Naval Battles of Miyako Bay and Hakodate (May 1869), Boshin War commemorative postcards, c. 1930. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo