See also:

Kamuro (attendant) at Yoshiwara, c. 1910

“By the 1760s … the tayo and koshi had disappeared in Yoshiwara and had been supplanted by the oiran, the highest ranking courtesans.

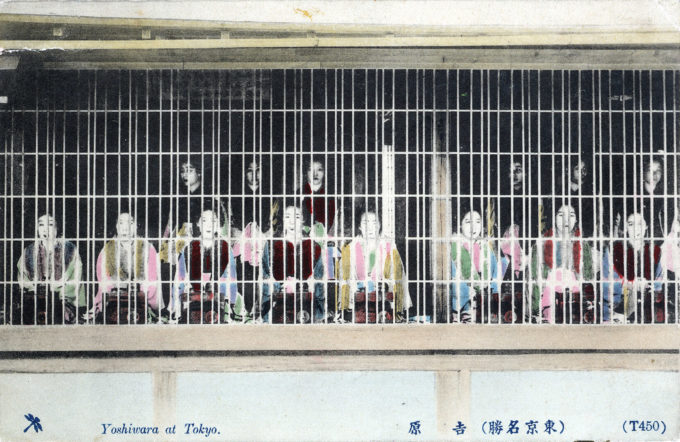

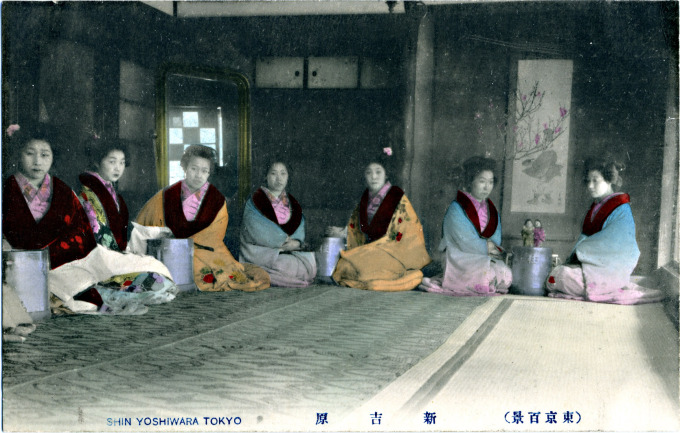

“The highest oiran were the yobidashi (literally, persons on call), who could be seen only be making an appointment through a teahouse. The next level of oiran was the chusan, who were displayed for selection in the latticed parlors.

“The third level, originally below that of an oiran , was the zashikimochi (parlor holder), who had her own parlor and anteroom, and the heyamochi (room holder), who had only one room, where she lived and met her clients.”

– Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900, edited by Haruo Shirane, 2008

- Yoshiwara prostitutes behind a brothel grate, c. 1910.

- Yoshiwara prostitutes behind a brothel grate, c. 1910.

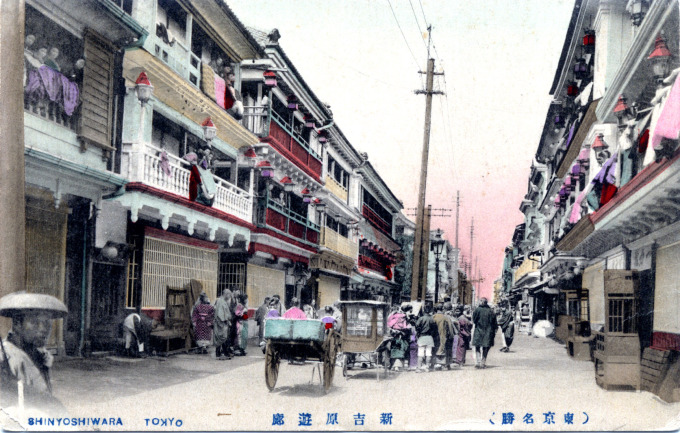

If any one area of Tokyo was able to hold on the longest to the mystique and charms of feudal Edo it was Yoshiwara [good luck meadow], the city’s most famous “licensed quarter.” Tokyo Yoshiwara was the most famous, most refined and most cultured of the city’s licensed quarters.

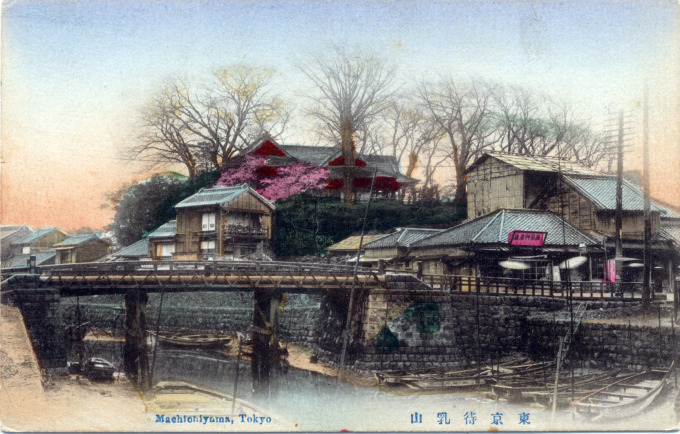

The location of Yoshiwara, walking distance north of the Asakusa temples, accessible by road or canal from Machiyama where trysts were arranged.

More so than at Shimbashi or Akasaka, Yoshiwara’s customers crossed all manner of social class; the itinerant and the noble were given equal access to Yoshiwara’s charms. (Samurai, however, had to remove their swords before entering the gated district.)

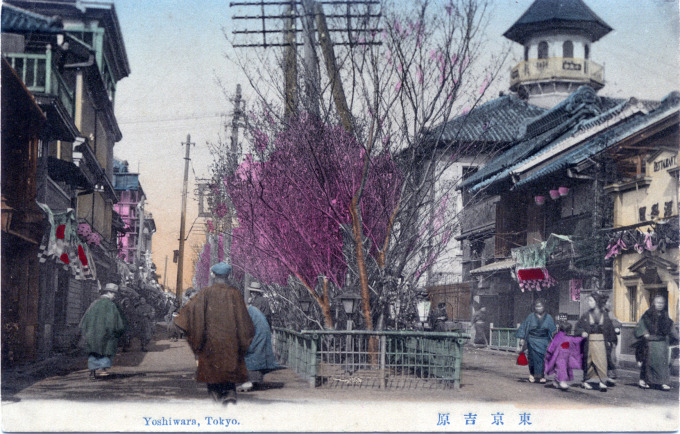

Upon the O-mon [Great gate], through which the district’s clientele would pass, was inscribed the Fukuchi poem above. Outwardly oblique, the stanzas referred to the custom of viewing in springtime (the “morning”) the many blossoming cherry trees planted down the middle of Yoshiwara’s main street, Nakano-cho, while the nighttime hours were alight with thousands of lanterns mimicking the appearance of fall foliage (the “autumn”). Business in Yoshiwara was so brisk it was sometimes referred to as the “Nightless City”.

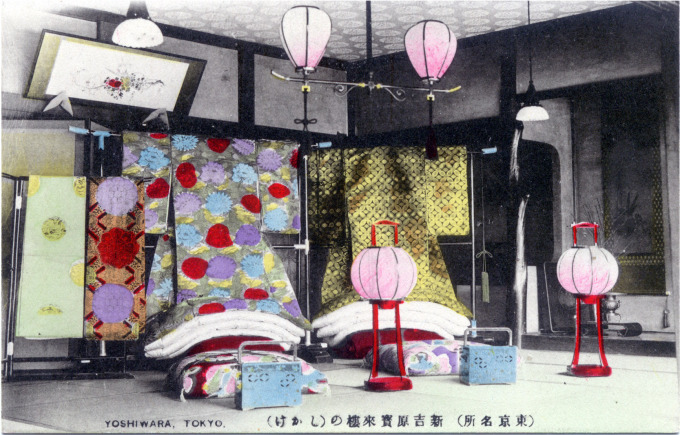

A Yoshiwara brothel, Tokyo, c. 1910. Chusan, the second level of oiran, were placed on display in latticed parlors visible from the street.

The name “Yoshiwara” was liberally applied throughout the country to many of Japan’s prostitution districts even after the Restoration. (Yokohama and Osaka both had Yoshiwara red-light districts.)

Edo-era Yoshiwara was originally a district found within the city limits but was, in the aftermath of the famously disastrous Furisode kwaji [Fire of the long-sleeved garment] in 1657, relocated outside the city-proper by puriant authorities to paddy fields north of Asakusa.

Fire and earthquakes would continue to change the outward appearance of Yoshiwara over the years but it would not be until 1958 — 300 years after it was first incorporated — when prostitution was officially abolished nationwide before the bloom finally fell from Yoshiwara’s blossom.

- Machi-chi-yama tea houses, Tokyo, c. 1910, where Yoshiwara trysts were arranged.

- Main Gate (Omon), Yoshiwara, c. 1910.

“About 1 m. to the N. of Asakusa Park lies the world-famed Yoshiwara, the principal quarter inhabited by the licensed hetairte of the metropolis.

“Many of the houses within this district are almost palatial in appearance, and in the evening present a spectacle probably unparalleled in any other country, but reproduced on a smaller scale in the provincial Japanese cities.

“The unfortunate inmates, decked out in gorgeous raiment, sit in rows with gold screens behind, and protected from the outside by iron bars.

“As the whole quarter is under special municipal surveillance, perfect order prevails, enabling the stranger to study, while walking along the streets, the manner in which the Japanese have solved one of the vexed questions of all ages.

“Their method, though running counter to Anglo-Saxon ideas, preserves Tokyo from the disorderly scenes that obtrude themselves on the passer-by in our western cities.”

– A Handbook for Travellers in Japan, by Basil Hall Chamberlain & W.B. Mason, 1901

- Yoshiwara oiran and kamuro (attendants), c. 1910.

- Yoshiwara oiran (prostitutes), c. 1910.

“In Japan it is not the wedding-ring which is the sign-manual of a married woman, but the dressing of her hair and the length of her kimono sleeves. A moosme [sic] must not have such long sleeves as a matron, and her hair is less elaborately dressed.

“The tying of an obi in front of the waist instead of behind is a sign that a woman belongs to the ‘oldest profession in the world,’ but such a sight is seldom seen outside the limits of the Yoshiwara, or on the stage, where the heroines of the popular drama, as I have already mentioned, are mostly low women.

“Gay hairpins, of enormous length and variety, standing out from a woman’s head like the pegs of a fiddle, are also the signs by which ye shall know the women who are compelled to live in the ‘city of no night.’

“Women of the higher classes only adorn their heads with veritable works of art in dull-gold lacquer, carved tortoise-shell, and coral; they are careful never to wear the skewer like ornaments, with which all the world is familiarised in the paintings on battledores and fans, of their less fortunate sisters.”

– More Queer Things About Japan, by Douglas Brooke & Norma Lorimer, 1905

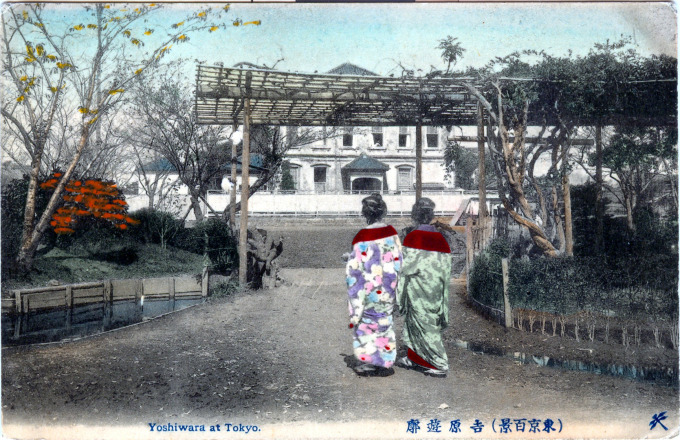

Views of Yoshiwara, 1900-1930

- Nectarine No. 9 brothel, c. 1910.

- Brothel bedding, Yoshiwara, c. 1910.

- Yoshiwara brothels, c. 1910.

- Yoshiwara Nakanocho shops, c. 1910.

- Yoshiwara oiran and attendants, c. 1910.

- Yoshiwara street scene, c. 1910.

- Arbor and gardens at Yoshiwara, c. 1910.

- Yoshiwara street scene, c. 1930.

![The Yoshiwara Prostitute House's [sic], c. 1910.](https://www.oldtokyo.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/yoshiwara-prostitutes-display-300-1024x6571-680x436.jpg)

Pingback: Shimbashi District, Tokyo. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Kamuro (attendant) at Yoshiwara, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Tokaido, Shinagawa, Tokyo, woodblock reprint c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Ryounkaku (Twelve-Storeys Tower), Asakusa | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Metropolis (1927): Blueprint for Urban-Dystopic Cinema | PlanetDystopia.net

Pingback: Metropolis (1927): Blaupause Urban-Dystopischen Kinos | PlanetDystopia.net

Pingback: SAKI & Bitches returns with Hana Machi an exhibition focusing on the lives of the Yujo of Imperial Japan - Inspiring City

Pingback: "A procession of oiran at Yoshiwara", c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Tokyo letteraria: sulle tracce di Higuchi Ichiyō

Pingback: "Maruyama-machi" (Licensed quarter), Nagasaki, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Asahi Rou “House of the Rising Sun” by Chiaki Naomi Lyrics – Translation – My Mahoroba

Pingback: ทำความรู้จัก “ย่านโยชิวาระ” พื้นหลังดาบพิฆาตอสูร ย่านเริงรมย์ – Social Multiculious Forum