See also:

Iwaya-furo, Kawaji Spa, c. 1920

The Natural Sand Baths and Onsen, Beppu, c. 1910-1930

Hot Spring Tea House [at] Tonosawa, near Miyanoshita, c. 1920

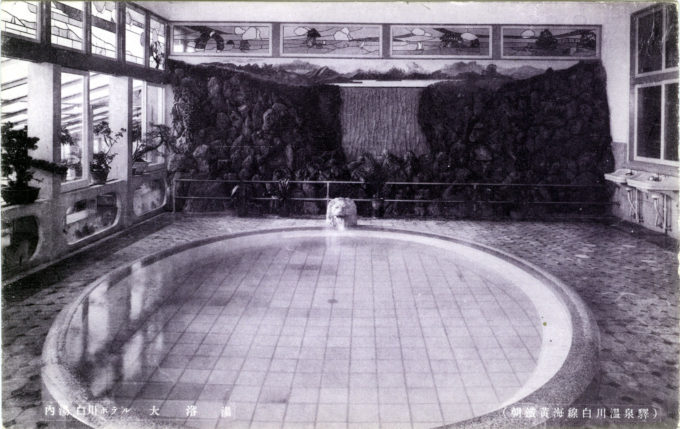

Hot springs swimming pool, Fujiya Hotel, Miyanoshita, c. 1930

“In the beginning, hot springs were managed by nearby temples. But, in the middle ages, feudal domains became involved, too. In the Edo period, the feudal domains took over control of the administration, which was then entrusted to villages or feudal officials.

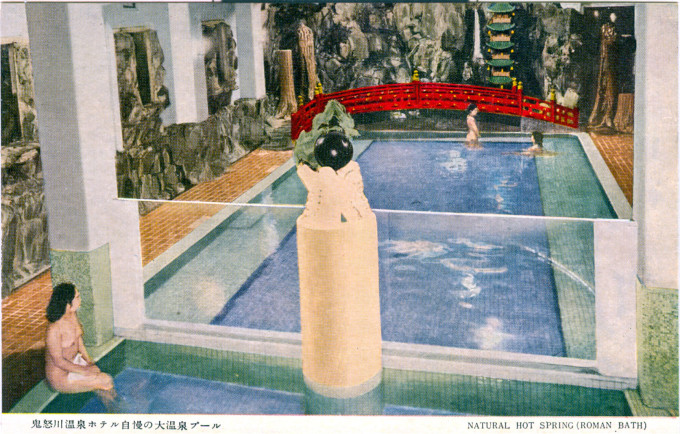

“Basically, spas can be divided into places where a few lodges had a monopoly on the hot water, like Beppu (also used by the Shogunate to assist in the healing of wounded warriors) and Atami, and settlements where the hot spring was provided to visitors in a public bath, as in the case of Arima or Dogo.

“… In the Edo period, visiting hot springs became common not only among feudal lords and samurai but also common people, and the basic structures of today’s spa settlements were completed … in the eighteenth century, medical publications and guidebooks helped to increase the popularity of hot springs … A guidebook from 1810 introduced 292 onsen around the country, listed by province along the major travel routes. By the late Edo period, onsen rankings in the form of pamphlets bought as souvenirs became increasingly popular. The oldest know pamphlet dates from 1817 and lists ninety-six hot springs arranged like a Sumo tournament ranking, with the hot springs of the ‘east’ competing against the ‘west’.”

– Japanese Tourism: Spaces, Places and Structures, by Caroline Funck and Malcolm Cooper, 2013

“We read in the Japanese mythology that the god Izanagi, on returning from a visit to his dead wife in Hades, purified himself in the waters of a stream. Ceremonial purifications continue to form part of the Shinto ritual. But viewed generally, the cleanliness in which the Japanese excel the rest of mankind has nothing to do with godliness. They are clean for the personal satisfaction of being clean.

“Their hot baths – for they almost all bathe in very hot water of about 110° Fahrenheit – also help to keep them warm in winter. For though moderately hot water gives a chilly reaction, this is not the case when the water is extremely hot; neither is there then any fear of catching cold.

“… Generally, but not always, a barrier separates the sexes from each other. Where there are neither bathing establishments nor private bath-rooms, the people take their tubs out-of-doors, unless indeed a policeman, charged with carrying out the modern regulations, happen to be prowling about the neighbourhood. For cleanliness is more esteemed by the Japanese than our artificial Western prudery. As the editor of the Japan Mail has well said, ‘The nude is seen in Japan but is not looked at.’

“… At Kawara-yu, a tiny spa not far from Ikao in the province of Joshu – one of those places of which there are many in Japan which look as if they were at the very end of the World, so steep are the mountains shutting them in on every side – the bathers stay in the water for a month on end, with a stone on their lap to prevent them from floating in their sleep.”

– Things Japanese: Being Notes on Various Subjects Connected with Japan for the Use of Travellers and Others, by Basil Hall Chamberlain, 1902

“Japan is peppered with volcanic hot springs, known as onsen. Communal bathing in these has been a custom for centuries, as a religious ritual (from the Shinto emphasis on purification) for health cure, or just for pleasure. Many spa baths tap into natural volcanic activity, taming the thermal waters; some artificially heated and enhanced with therapeutic herbal concoctions. A visit to an onsen is an antidote to the hectic pace of urban life, a chance to recuperate after sightseeing or business, and an insight into a soothing and companionable side of Japan.

“The variety of onsen is phenomenal. They come in every format: natural and man-made; indoors and outdoors; as small as bath and as large as a swimming pool; lobster-hot and lukewarm, milky and clear; sulfurously foul-smelling and sweetly earthy. Certain chemical compounds in the waters are said to help different ailments, such as arthritis, hypertension, and skin problems.

“Etiquette at onsen is similar to that of communal baths in ryokan. Pools are usually single-sex; women rarely use mixed pools, except perhaps at night, when mixed bathing is more acceptable. Occasionally people in outdoor pools (rotenburo) wear swimsuits, but mostly everyone is naked. Nonetheless, the atmosphere is not sleazy, and visitor need have no qualms.

“As with any Japanese bath, wash and rinse yourself thoroughly at the showers and taps provided outside the bath and take great care not to get any soap or shampoo in the bath itself. The small towel provided can be used as a washcloth, draped across strategic parts of your body, placed on your head while in the pool (said to prevent fainting), or used to dry yourself when you emerge.”

– DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Japan, John Turp, 2000

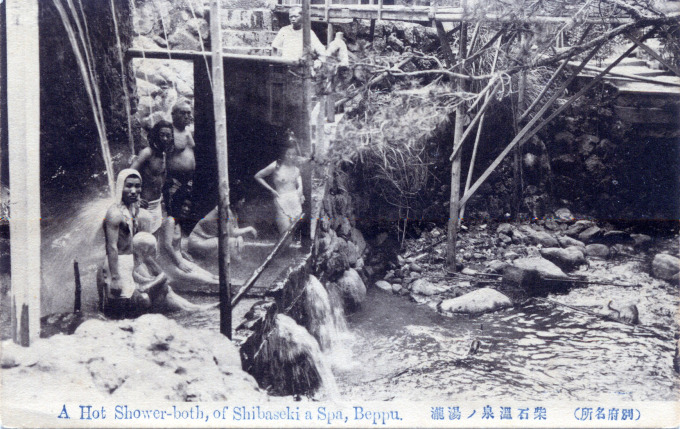

![Outdoor <em>onsen</em> [hot spring], c. 1910.](https://www.oldtokyo.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/scan0003-680x447.jpg)

Pingback: The Natural Sand Baths and Onsen, Beppu, c. 1910-1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Iwaya-Furo, Kawaji Spa, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Ofuro (bath) culture, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Kinosaki Hot Spring, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: "Sea Water Bath of Kaomega-saki", Tsuruga, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Matsudaya Hotel, Yuda Spa, Yamaguchi Prefecture, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo