See also:

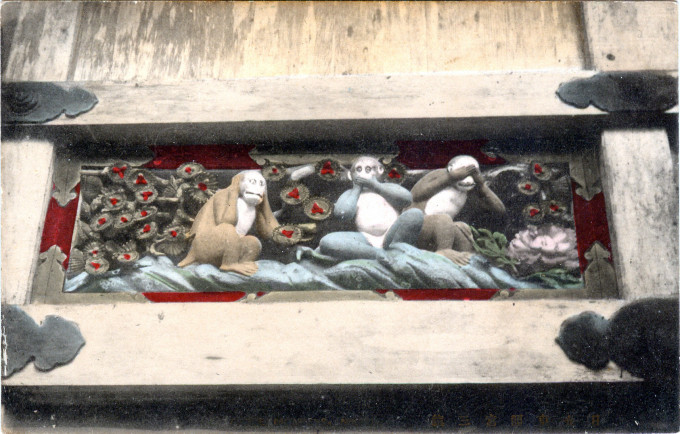

Mizaru, Kikazaru & Iwazaru (See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil), c. 1910.

Nikko Hotel, Nikko, c. 1910.

Kanaya Hotel, c. 1920.

A View of Lake Chuzenji, Nikko, c. 1910.

Ice Skating at Kanaya Hotel, Nikko, c. 1930.

“While at Tokyo you should by all means visit Nikko, only five hours’ ride by rail, upon which city nature has showered beauty with a lavish hand.

“Of Nikko more has been written and spoken by foreigners than any other place in Japan. And the Japanese will tell you if you have not visited Nikko you have not seen Japan at all.

“From its magnificent slopes and mountain tops, covered with evergreens and adorned with temples, one looks down upon a landscape which no artist could hope to adequately portray, and which should not be missed by those fortunate enough to have set foot on the shores of the Mikado’s Kingdom.”

– Travels from the Grandeurs of the West to Mysteries of the East, Charlton Bristow Perkins, 1909

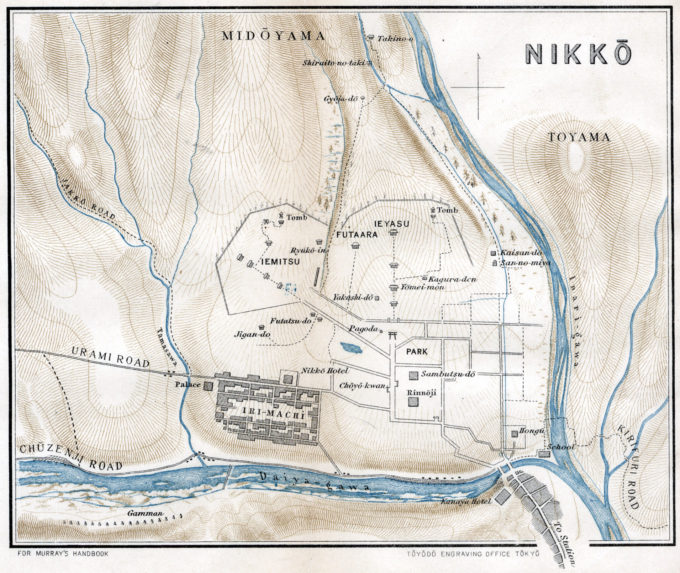

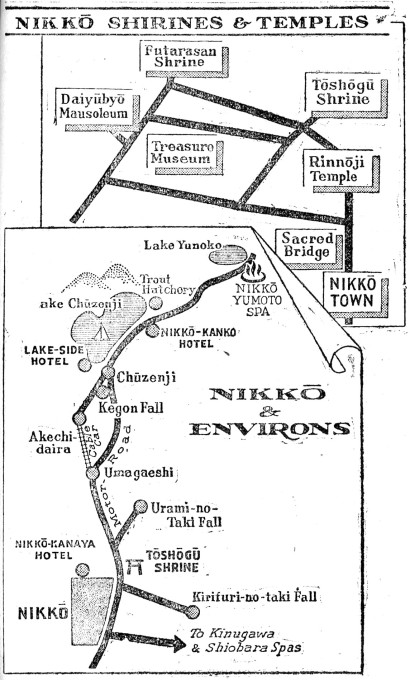

“Nikko (Sun’s brightness) is celebrated for its mountain scenery, its lake of Chiuzenji and for the many cascades to be found within easy travelling distance. The ‘Sacred Ground’ forms its greatest attraction.

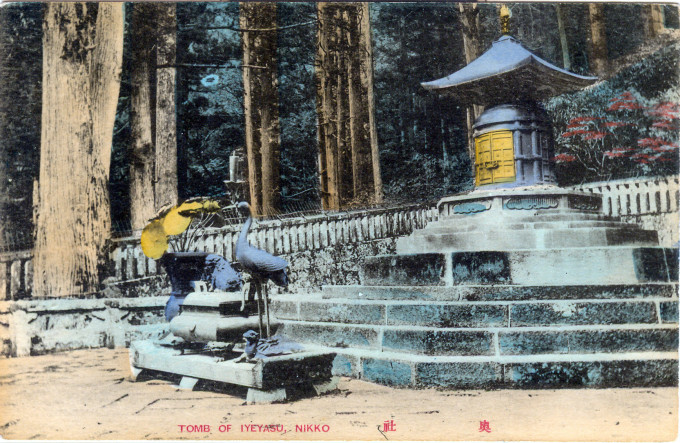

“Here is gorgeously entombed Iyeyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa dynasty of Shogun and his illustrious grandson Iyemitsu. The temples, although entirely of wood, are to all appearance as free of decay or deterioration as when they were built. The marvelously brilliant decorations of gold and lacquer, the exquisite carvings of birds and flowers, so realistic in conception and expression, are a surprise to those who have looked upon the elaborately wrought temples of Shiba, built at a later period.

“It would take many pages to enter on a detailed description of the many beautiful structures clustered on the sacred grounds of Nikko, and tell of the birds and trees, of the flowers and vines, the dragons, tigers, monkeys, lions, unicorns, phoenixes, elephants and fabulous beasts, conceived by the brains of enthusiastic devotees of the doctrines of Buddha, or of the gods that are chiseled for the contemplation of the devout – gods in blue, in green, and in vermilion; gods with fat bellies and big ears; gods with three toes and three fingers only; and one, the god of thunder, with only two toes and two fingers.

“To see the two mausolei only, one whole day is required, two days being lost going and returning.”

– Keeling’s Guide to Japan, A. Farsari, 1890

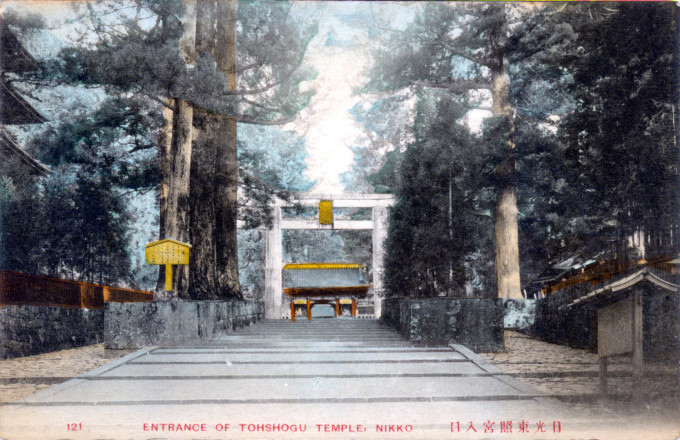

Toshogu Shrine

Tōshō-gū is dedicated to Tokugawa Iyeyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate. Initially built in 1617, during the Edo period, while Ieyasu’s son Hidetada was shogun, it was enlarged during the time of the third shogun, Iyemitsu. Iyeyasu is enshrined there, where his remains are also entombed.

Famous buildings at the Tōshō-gū include the richly decorated Yōmeimon, a gate that is also known as higurashi-no-mon. The latter name means ‘one could look at it until sundown, and not tire of seeing it’. The next gate is the karamon decorated with white ornaments. Nearby, a carving of the sleepy cat, Nemuri-neko, is attributed to Hidari Jingorō – a possibly fictitious early Edo period artist, sculptor and carpenter. Although various studies suggest he was active in the early Edo period (around 1596-1644), there are controversies about the historical existence of the person. Jingorō is believed to have created many famous deity sculptures located throughout Japan, and many legends have been told about him.

- Three Wise Monkeys, Sacred Horse Stable, Nikko, c. 1910.

- Nemuri-no-neko (Sleeping Cat) Shrine, Nikko, c. 1910.

The stable of the shrine’s sacred horses bears a famed carving of the three wise monkeys, who hear, speak and see no evil, a traditional symbol in Chinese and Japanese culture. The original five-story pagoda was donated by a daimyo [provincial lord] in 1650, but it was burned down during a fire, and was rebuilt in 1818. Each story represents a different element – earth, water, fire, wind and aether or void – in ascending order.

Futarasan Shrine & the Sacred Bridge

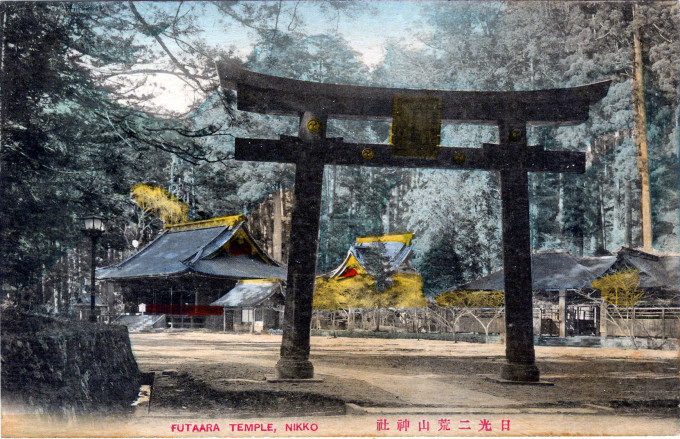

- Futarasan Shrine, Nikko, c.1910.

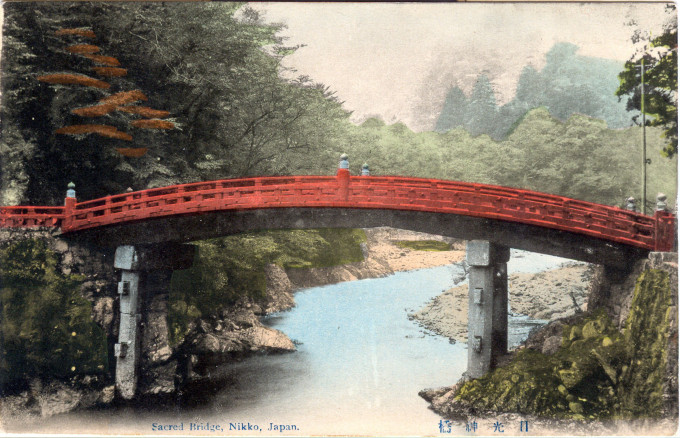

- The Sacred Bridge, Nikko, c. 1910.

From the wiki: “Futarasan jinja is a Shinto shrine in the city of Nikkō,. It is also known as Nikkō Futarasan Shrine, to distinguish it from the shrine in nearby Utsunomiya. Futarasan enshrines three deities: Ōkuninushi, Tagorihime, and Ajisukitakahikone. The Sacred Bridge crossing the Daiya River belongs to the Futarasan Shrine. The vermilion-lacquered structure is known as one of the three most beautiful bridges in Japan and was registered as a World Heritage in December 1999. According to legend, a priest named Shōdō and his followers climbed Mt. Nantai in the year 766 to pray for national prosperity. However, they could not cross the fast flowing Daiya River. Shōdō prayed and a 10 foot tall god named Jinja-Daiou appeared with two snakes twisted around his right arm. Jinja-Daiou released the blue and red snakes and they transformed themselves into a rainbow-like bridge covered with sedge, which Shōdō and his followers could use to cross the river. That is why this bridge is sometimes called Yamasugeno-jabashi (‘Snake Bridge of Sedge’).”

Pingback: Ice Skating at Kanaya Hotel, Nikko, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Tosho-gu Shrine, Ueno Park | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Kanaya Hotel, Nikko, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Nikko Hotel, Nikko, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: A View of Lake Chuzenji, Nikko, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Iwaya-Furo, Kawaji Spa, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Mizaru, Kikazaru & Iwazaru (See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil), c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Meiji Jingu (Shrine). | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Oumaya (Sacred Horse Stable) of Toshogu, Nikko, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Cryptomeria Road, Nikko, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Lake Chuzenji, Nikko, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Nezu Kaichiro, Chairman of the Tobu Railway, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Kegon Waterfall at Nikko, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: “Three Monkeys carving at Iyeyasu Temple”, Nikko, c. 1920. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo