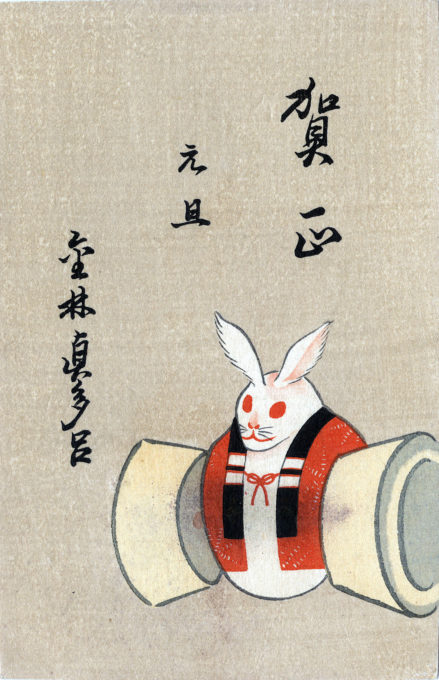

“Year of the Rabbit (Hare)” propaganda postcard, 1939. The postcard is captioned: “Pray for the longevity of the Imperial Army’s martial fortunes” with a very abstract representation of the zodiac critter. People born in the year of the Rabbit (or Hare) are the most fortunate. They are smooth talkers, talented, ambitious, virtuous and reserved. They have exceedingly fine taste and are regarded with admiration and trust. Born 2023, 2011, 1999, 1987, 1975, 1963, 1951, 1939, 1927, 1915.

See also:

Seven Lucky Gods of Japan, c. 1920.

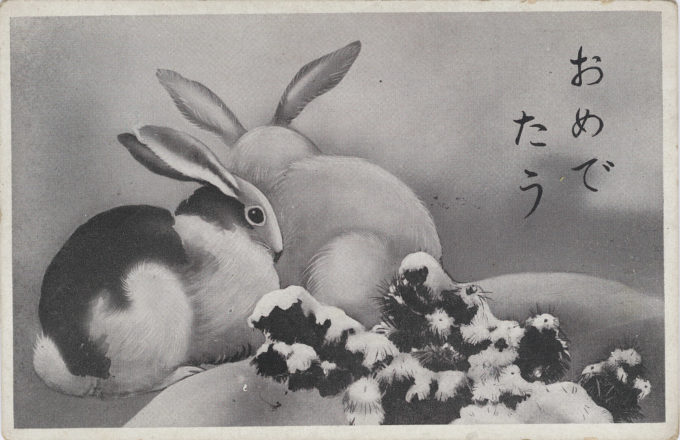

“People born in the Year of the Rabbit are the most fortunate. They are smooth talkers, talented and ambitious. Virtuous and reserved, they have exceedingly fine tastes, and other people regard them with admiration and deeply trust them. Rabbit people are always financially lucky. They have a fondness for mild gossip, but they are tactful and do not speak out willingly if they have to say something bad about someone.

“Rabbit people have to be goaded for quite a while before they lose their tempers, for by temperament they are placid. They are very clever at business, and if someone signs a contract with a rabbit person, there can be no backing out of it.

“Rabbit people would do well to marry persons born in either the Sheep, the Boar, or the Dog year. A bad marriage would be with someone born in the Dragon year, and the worst would be with someone from either the Rat or the Cock year.”

– Japanese Fortune Calendar, Reiko Chiba, 2011

- “Year of the Rabbit (Hare)”, New Years postcard, 1939.

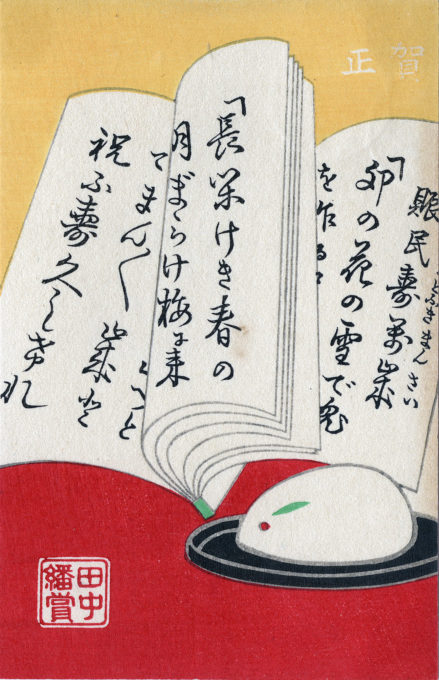

- “Year of the Rabbit (Hare)”, New Years postcard, 1939.

“In Japan, the hare is especially connected with the moon. The Sanskrit word for ‘moon’ means, literally, ‘one who carries the hare’ – which accounts for its association with the full moon for ages past in every quarter of the globe, except where the hare becomes ‘the man in the moon.’ Commonly, the hare with his mortar and pestle, is pictured as pounding the mochi, of which rice cakes are made.

“The hare appears early in Japanese tradition, or folklore, as is shown in the tale The White Hare of Inaba in the Kojiki (‘Record of Ancient Matters’), the earliest work in Japanese literature, dating from the year 712 – which contains the mythology and the earliest history of the nation.

“… ‘Hare Day’ also figures in folklore and customs. Thus the mayu-dama, a sort of Christmas tree decorated with cakes in honor of the silkworm, makes its appearance on whatever date in January may happen to be the ‘First Day of the Hare’ (Hatsu U), at which time a celebration is held at the Kameido Temple, Tokyo.

“And, on the first ‘Hare Day’ of the 10th month, there is a singular celebration at Wasa, Kishu province, called the ‘Laughing Festival of Wasa.’ The 10th month (October) is often called the ‘godless month’ because all the deities are supposed to repair to the great shrine in Izumo. It is said that, when this conclave was first convened, one deity mistook the date and did not appear until the conference was over, and, naturally, he was laughed at by the other deities. The Wasa festival commemorating that mistake, is a time of ‘merriment from morning till evening.’

“A number of heraldic designs utilize the hare, one or more, in various poses. Only a few proverbs center around the hare. ‘There’s not even the hair of a rabbit means that there is not even a small particle of a thing. ‘He who runs after two hares will not catch either’ has its counterpart in an Italian or English proverb. The ‘Hare Hour’ is the time between 5 and 7 a.m.”

– We Japanese, published by the Miyanoshita Fujiya Hotel, 1950