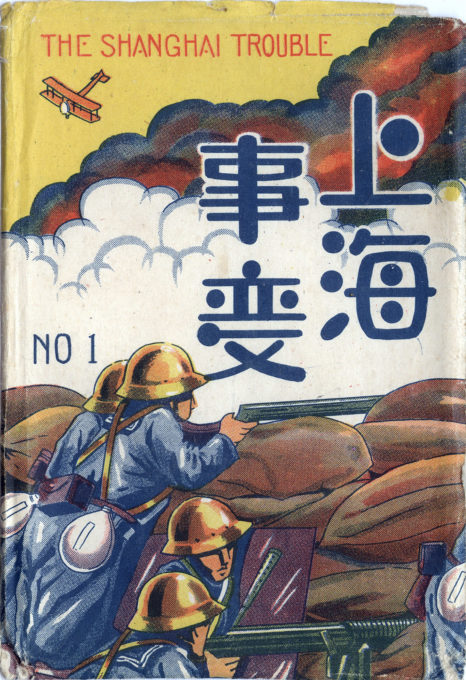

“Shanghai in 1932 was the scene of a fierce thirty-three-day fight between Chinese and Japanese.

“Was this a war or a mere ‘incident’? This bloody struggle that captured world headlines for five weeks in early 1932, followed by a longer period of contentious negotiations, shrank to but a footnote in history once the Sino-Japanese war erupted in 1937 and merged with the global conflagration in 1941. A second huge battle at Shanghai in 1937 further confused the 1932 memories of even the residents.

“Historians of modern China and the 1930s also became content to trivialize Shanghai’s 1932 conflict with a sentence or paragraph based on widely accepted generalizations but little fact.”

– China’s Trial by Fire: The Shanghai War of 1932, by Donald A. Jordan, 2001

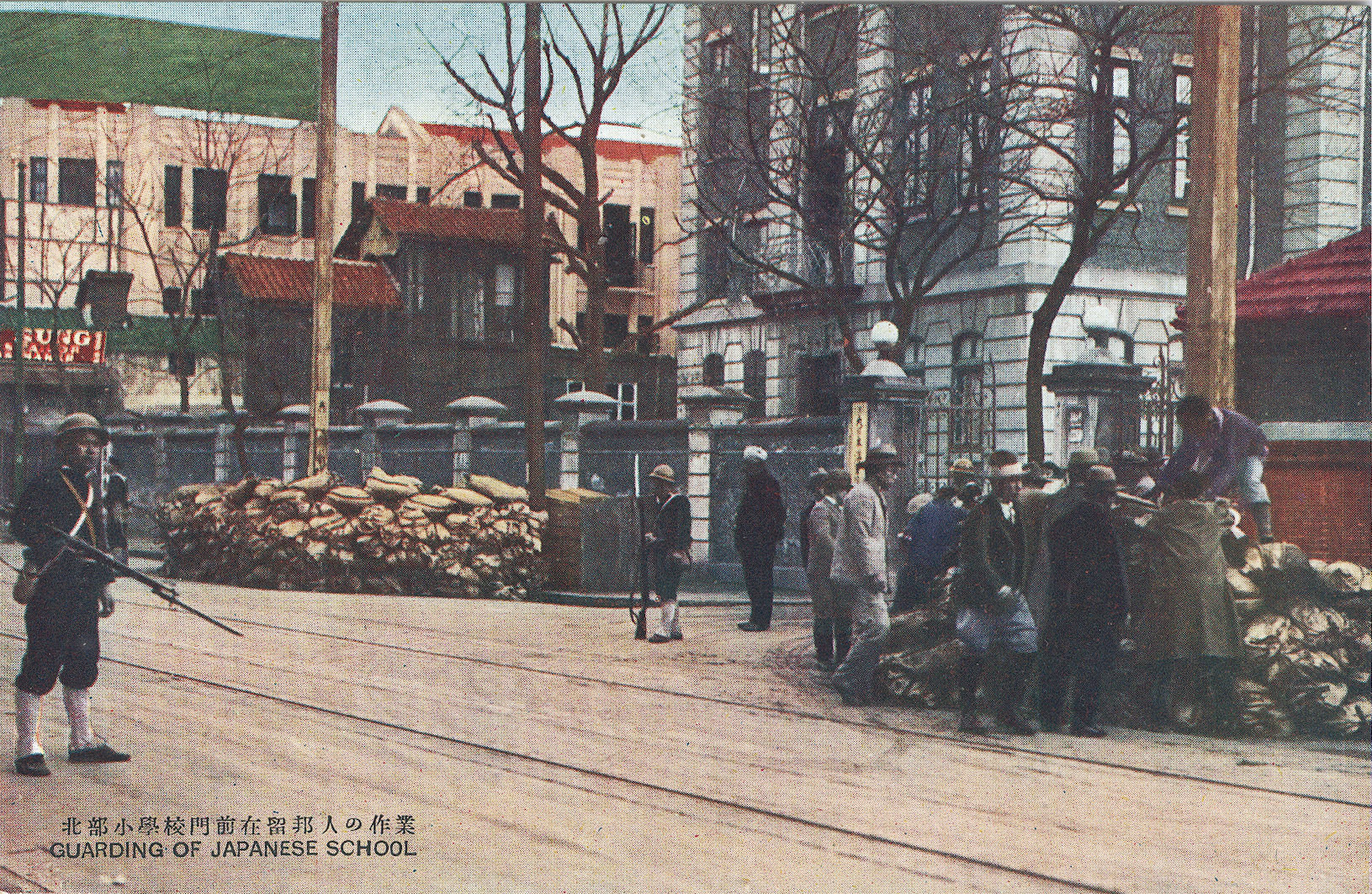

Imperial Japanese Navy Shanghai Naval Landing Force (SNLF) marines “at work completing the wire barricade”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

See also:

Imperial Japanese Navy Shanghai Naval Landing Force (SNLF) Marine, 1932.

“Shortly after New Year [1932], the crisis in China escalated dangerously, even as fighting in Manchuria gradually ceased … The scene was now Shanghai.

“It was China’s largest and most prosperous city, and while most inhabitants were Chinese, its advantageous position at the Yangzte estuary had attracted thousands of foreigners. Many had made Shanghai their home, and two large Western districts, the International Settlement and the French Concession, had emerged in the center of the city. One could walk down streets with names such as Edinburgh Road and Avenue Joffre and easily forget this was not some Europeans capital.

Map: “Shanghai Trouble”, 1932, showing the various districts assigned to foreign military forces by an international consent agreed to in January, 1932.

“Japanese merchants and settlers had also established their own district in Shanghai, in an area that had come to be known among the locals as ‘Little Tokyo’. It was guarded by a small garrison unit, just as American and British soldiers were protecting their nations’ interests in the city.

“… On January 18, 1932, five Japanese monks were attacked by a Chinese mob as they were chanting sutras near the Chinese-owned San Yu towel factory, a known hotbed of anti-Japanese activism. One of the monks died and two were seriously injured. Japanese vigilantes retaliated by burning down the towel factory.

“The situation could no longer be reined in. On the surface it seemed like a clear-cut case of tempers boiling over but, in fact, foul play was involved. The entire incident was precipitated by the Japanese themselves. A military attaché employed at the Japanese diplomatic representation had paid the Chinese mob to carry out the attack on the monks. Japan needed a high-profile, local conflict in the east of China to divert attention from events up north in Manchuria.”

“The tension quickly spiraled, and within days, Shanghai’s small Japanese garrison was involved in intense urban combat with Chinese forces … Initially, 30,000 Chinese soldiers, including battle-hardened veterans from the 19th Route Army, were confronting fewer than 2,000 Japanese. They were from the Japanese Navy’s Special Naval Landing Force, an amphibious unit similar to the American Marines.

“… At times, the battle assumed an almost surreal character. In the International Settlement and the French Concession, people continued their daily business, going to work and school while the war was happening just blocks away … American journalist Hallett Abend described how one of the early skirmishes attracted a crowd watching from the relative security of the foreign district: ‘They stood around the sloppy streets, smoking cigarettes, occasionally drinking liquor from bottles and enjoying sandwiches and hot coffee procured from nearby cafés which had not yet closed their doors.”

– War in the Far East: Storm Clouds Over the Pacific, 1931-1941, by Peter Harmsen, 2018

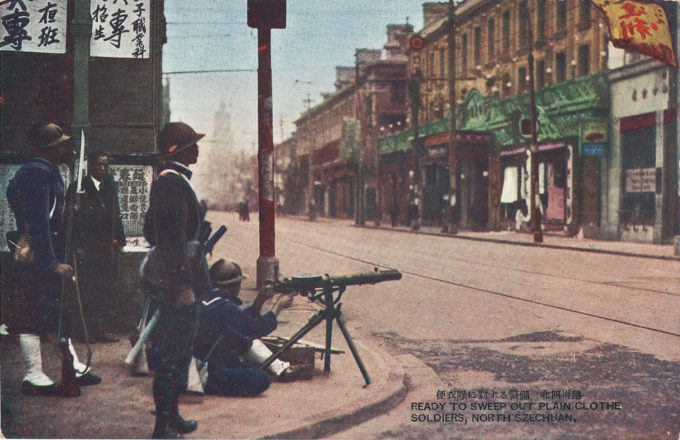

Shortly before midnight on January 28, plainclothed Chinese troops infiltrated the Hongkew district in the Japanese Defense Sector and then fired upon Japanese sailors leaving their headquarters. Three thousand Japanese sailors were mobilized in response, attacking the neighboring district of Chapei and assuming control of the “de facto” Japanese settlement in Hongkew.

- “Ready to sweep out plain clothe(d) soldiers, North Szechuan”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

- “In action to make a dash at plain clothe(d) soldiers, North Szechuan Road”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

“The January 28 Incident or Shanghai Trouble (January 28 – March 3, 1932) was a conflict that took place in the Shanghai International Settlement between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan.

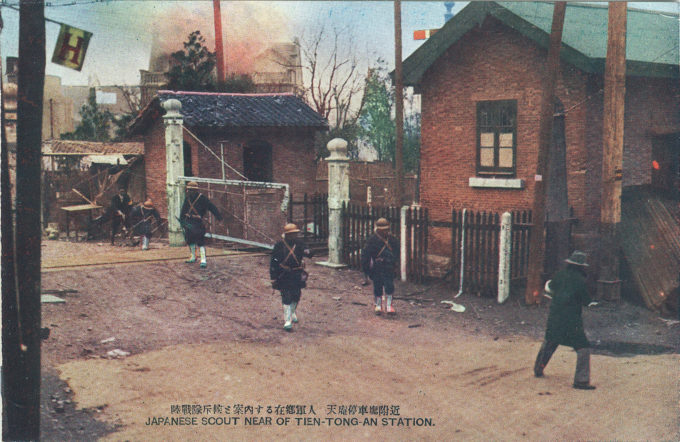

“Japanese army officers, defying higher authorities, had provoked anti-Japanese demonstrations in the International Settlement following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria … Heavy fighting broke out, and China appealed with no success to the League of Nations. A truce was finally reached on May 5, calling for Japanese military withdrawal, and an end to Chinese boycotts of Japanese products.

“Internationally, the episode intensified opposition to Japan’s aggression in Asia. But, the episode also helped undermine civilian rule in Tokyo; Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi would be assassinated on May 15, 1932, effectively marking the end of civilian political control over government decisions until after the Pacific War.”

– Wikipedia

- “Japanese scout near Tien-Tong-An Station”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

- “Blue jackets ‘Dare to Die'”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

- “Firing from San-Yi-Lee”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

- “Landing force in the near of Isis Theatre”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

- “Cha-Pei District after battle”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

- “Navy plane dropped bomb(s)”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

- “Landing force sweep out Chinese troops, Range Road”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

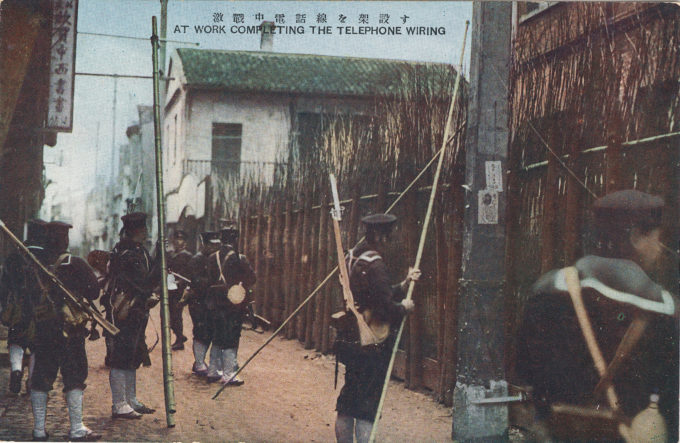

- “At work completing the telephone wiring”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

- “Landing force in front of Ju-Kong Road”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

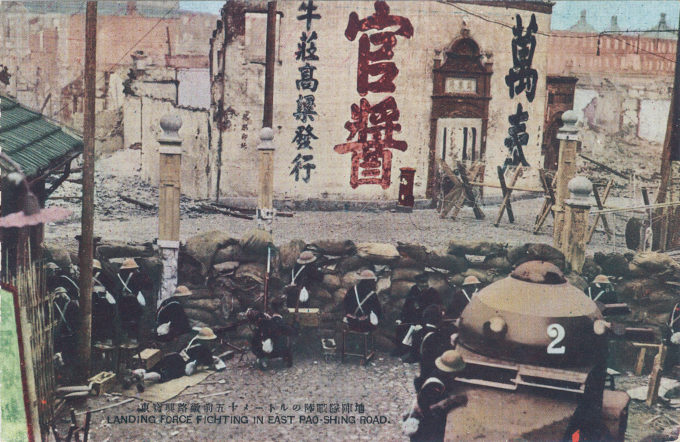

- “Landing force fighting in East Pao-Shing Road”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

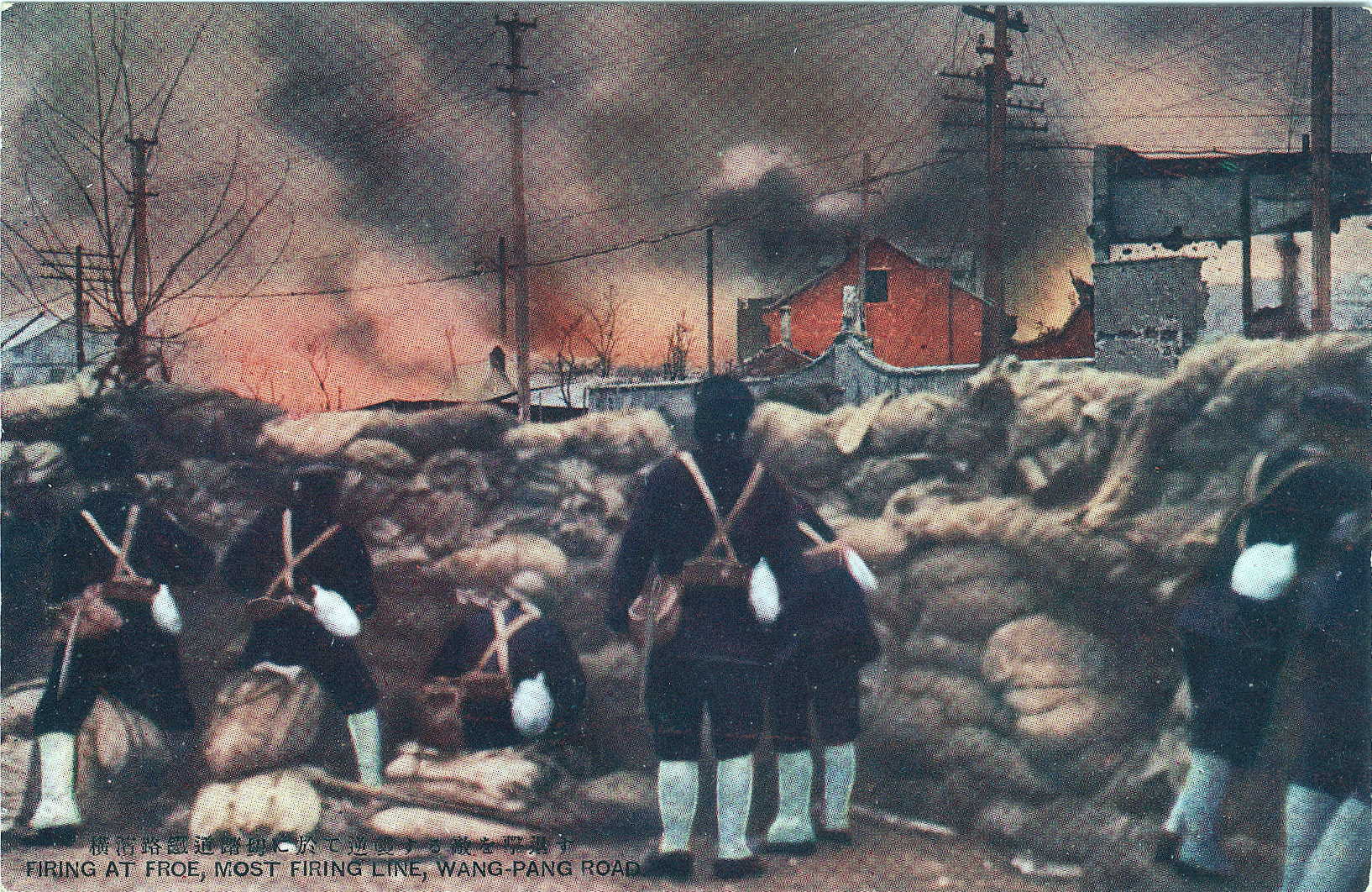

- “Firing at foe, Wang-Pang Road”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.

- “Firing from Ju-Kong Road”, The Shanghai Trouble postcard series, 1932.