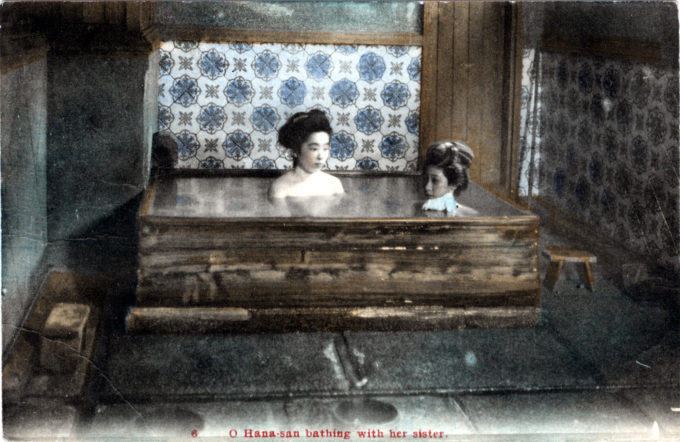

“Both sexes are very partial to bathing, and consequently public baths are numerous. In large towns they may be counted by hundreds. Until lately, men and women, boys and girls, bathed together indiscriminately. But now, in Tokio and other large towns, a railing divides the males from the females. This is only sufficient to prevent the mixing of the sexes, but not to screen them from being seen by each other. The hot water is contained in oblong wooden vats, 8 to 10 feet in length, 3 or 4 feet wide and 3-1/2 feet deep. These are heated from behind, by burning wood in large brass cylinders, the closed end of which communicates with the water.

“There are two of these vats in every bath-house, one being used by men, and the other by women. The water has a temperature between 100° and 113° Far. The women do not enter the bath at once, after disrobing; but throwing a few pailfuls of hot water over the body, squat on a low square flooring, and scrub themselves well with bran, contained in a little cotton bag. This being done, they again throw hot water over themselves, and enter the bath. This is performed twice or thrice. The operations of the male bathers are of shorter duration.”

– Keeling’s Guide to Japan, by W.E.L. Keeling & A. Fasari, 1890

“[A] bath in a Japanese house adds considerably to the joy of living.

“It is not much to look at; mainly an oval, but deep, wooden tub, in one end of which there is a little furnace to heat the water. A tin pipe carries the smoke of the charcoal or coal out of doors.

“My Japanese bathroom has wood-paneled walls and a cement floor. Above the floor, a raised platform made of wooden slats makes it convenient to descend into the depths of the water; also, the platform provides an outlet for the overflow from the tub. There is nothing to spoil so the bather, porpoise-like, may splash about, heedless of the consequences. Along one entire side of the bathroom, there is a frosted-glass window.

“… I sit on a stool, with a small tub of hot water in front of me, and armed with soup and towel and a wooden hand dipper, being to wash and rinse to my heart’s content. Meanwhile, if the window is open, I can see a flourishing pine tree, with blue-green fluffy branches, as in a Japanese painting. It is a sentinel tree of the shrine that adjoins my house.

“After the cleansing has been carried out, it is time to step down into the brimming tub. My entrance causes a displacement, and it is a truly luxurious feeling of having more than enough hot water and to spare – even sufficient to waste – that I hear it pouring riotously over the rim of the tub. Sitting down in the depths, with only my head out of water, I feel a sense of pleasure that may have been inherited from some amphibious ancestor.

“… Never again shall I be content with a western bath, its cold porcelain surface, coffin-like shape, and only one part of my anatomy immersed at a time! Give me the sensible wooden tub of the common people of Japan, in which I can soak up to my ears while I commune with nature outside my window!”

– Tokyo Vignettes, by Zoe Kincaid, 1933