See also:

Yedogawa, Tokyo, c. 1910

Cherry Blossoms at Mukojima, c. 1910.

Ueno Park, 1910.

Shiba Park

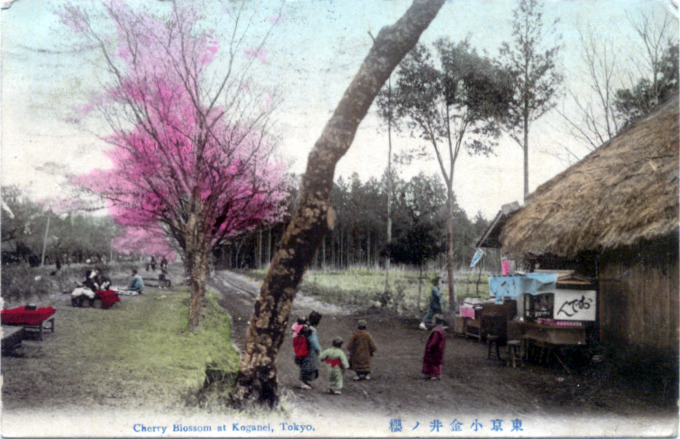

Koganei Cherry Blossoms, c. 1910.

“‘Without wine, how can one enjoy the view of the blooming cherry?’ sang the Emperor Richiu fifteen hundred years ago, when a petal fell into his wine-cup.”

– The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Vol. 79, Elizah Ruhamah Scidmore, 1910

What roses are to the West, cherry blossoms are to Japan. Cultivated for its blossoms, because it bears no fruit, the luscious canopies of delicate pink Prunus serrulata bring forth crowds all over Japan every spring for viewing in a ritual colloquially known as O-hanami [cherry blossom viewing].

In the Kanto Plain, where Tokyo is located, blossom-viewing is usually any time from late March to early April depending on the weather. There are thousands of cherry tree varieties planted throughout Japan. Most in Tokyo are of the somei yoshino and yamazakuea varieties.

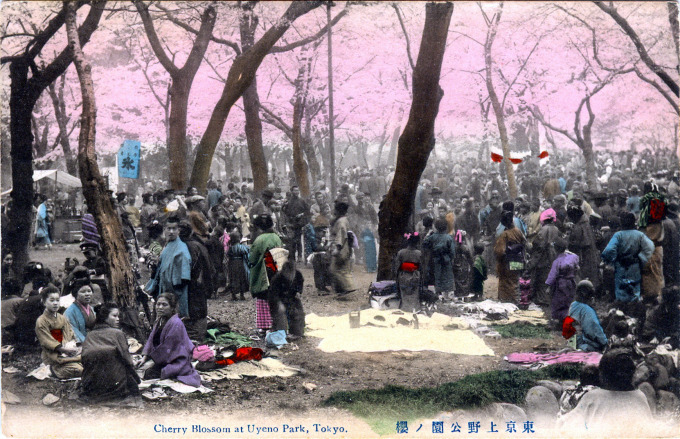

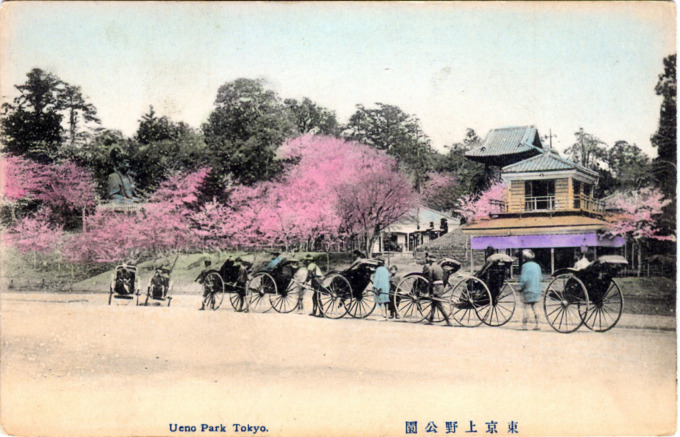

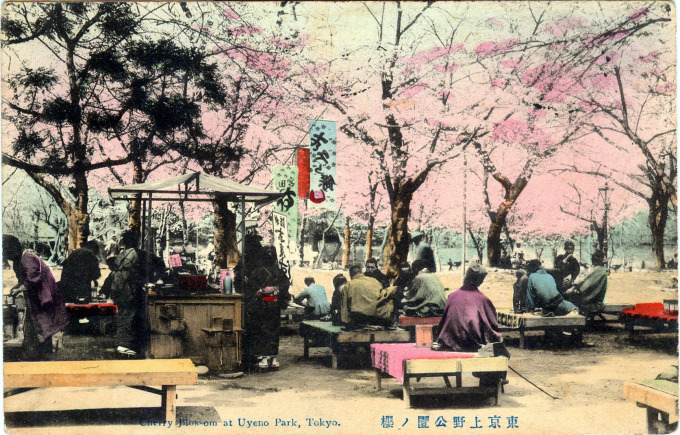

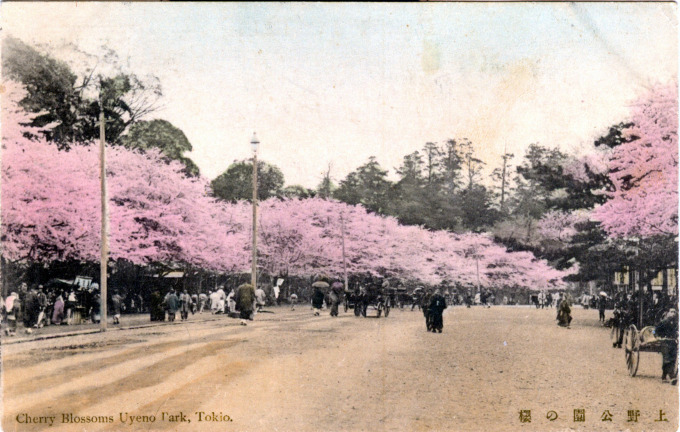

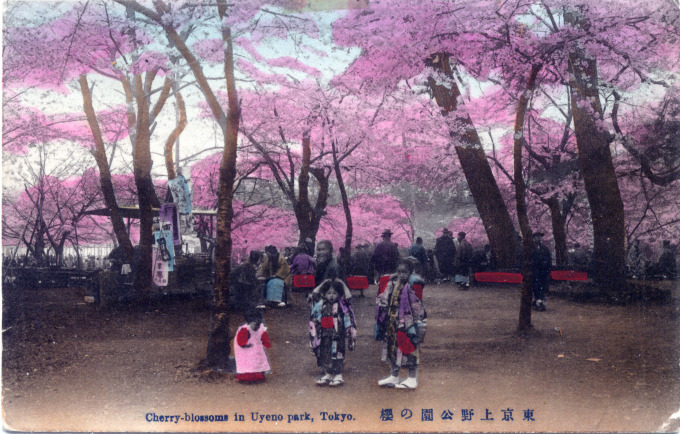

By far, the most popular destination in Tokyo (if not the whole of Japan) for O-hanami each spring is Ueno Park. More than 1000 cherry trees burst forth with blossoms and fill the park with their delicate pink presence. Much the same viewing ritual as today prevailed a century ago at Ueno Park. Scores of admirers — numbering into the tens of thousands at any one time — would gather on tatami mats beneath the flowering canopies, and imbibe in great quantities of sake [rice wine] and umeboshi [dried plums]. The evening hours are an especially popular time to view the blossoms.

さまざまの

事おもひ出す

櫻かなHow many, many things

They call to mind

These cherry-blossoms!– Matsuo Basho (1644–1694)

“The first characteristic of the hanami period is its brevity, like a sudden emergence: only a few days, between the end of March and the beginning of April in Tokyo. It is short but, even today, it is one of the most intense and festive moments in the year.

“First of all, hanami has an important collective meaning: it marks reentering. Actually, in Japan, the year starts in April for schools, universities, businesses, companies, the Parliament, new TV programs with new hosts and newscasters, the baseball championship, and so on. This social and cultural passage happens in a specific atmosphere, attuned to the growing rhythm of nature. Thus, it impresses the natural order on society, and anchors the social order in nature.

“New employees, who were recruited in autumn or winter and graduated in March, start work on 1 April, and one of their first tasks may concern hanami: they go to the park, choose a good place under cherry trees, mark it with vinyl sheets and cardboard. Although some are buying drinks and foods, others guard the place for the whole day, under very changeable weather, waiting for all the colleagues to come in the evening to eat and drink for part of the night.”

– Performance and Appropriation: Profane Rituals in Gardens and Landscapes, Michel Conan, 2007

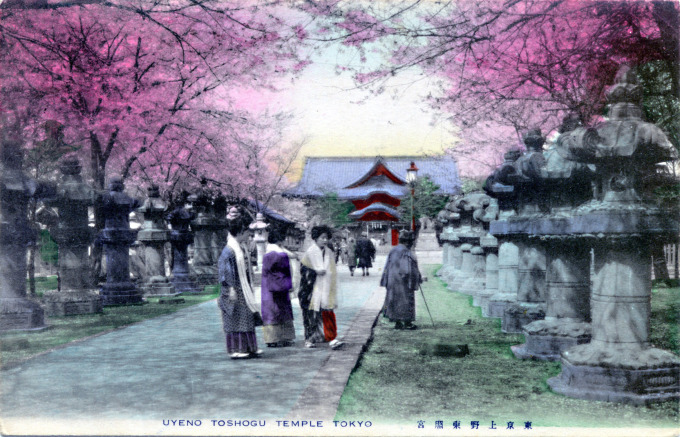

Ueno Park Cherry Blossoms

“Ueno is ideal for hanami; even I, a complete outsider, can see that.

“The nearly bare black boughs, fringed in pink blossoms, arch over the paved lanes. Vendors plants their wooden pushcarts and raise their roofs against the rain. Red and white banners line and sometimes cross the avenues. Everywhere there are men in suits and expensive full-length rain coats sloshing right and left, and mothers with children. Some of the kids are dressed up in holsters and toy guns, chaps and boots – American cowboys.

“A dozen men sit on a blue sheet under a transparent rain tarp anchored to the branches of a cherry tree, drinking and laughing, their shopping bags and unsheathed umbrellas at their sides, their shoes removed.

“A man sits alone on the tiniest lawn chair we have even seen, a foot off the ground, hunched over a comic book, the square he is guarding outlined in white twine weighted down at the four corners with rocks. The pigeons circle.”

– The Sudden Disappearance of Japan, by J.D. Brown, 1994

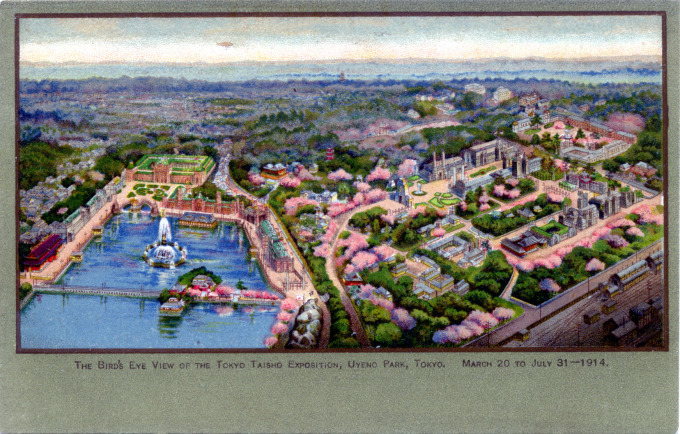

- Aerial view of Uyeno Park cherry blossoms, 1914.

- Cherry Blossoms at Uyeno Park, c. 1910.

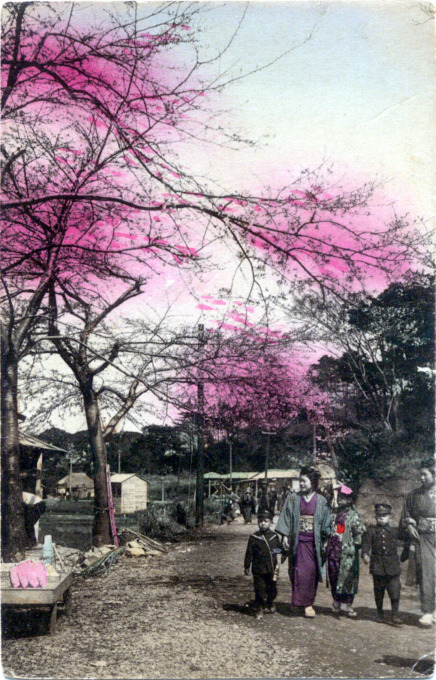

- Uyeno Park cherry blossoms, c. 1910.

- Tatami mats and refreshments during O-hanami at Uyeno Park, c. 1910.

- Canopies of sakura at Uyeno Park, c. 1910.

- Cherry blossoms and Saigo statue at Uyeno Park, c. 1910.

- Toshogu shrine under a canopy of cherry blossoms, Uyeno Park, c. 1910.

- Canopy of cherry blossoms at Uyeno Park, c. 1910.

- Children and cherry blossom viewing, Uyeno Park, c. 1910.

- Cherry blossoms at Uyeno Park, c. 1910.

In Japan, cherry blossoms can symbolize an enduring metaphor for the ephemeral nature of life. The transience of the blossoms – extreme beauty, then quick death – has often been associated with mortality; for this reason, cherry blossoms are richly symbolic in the Japanese arts. During World War II, cherry blossom imagery and symbolism was used in Japan to motivate workers, to stoke nationalism and militarism among the populace. The government even encouraged the people to believe that the souls of downed warriors would be reincarnated in the blossoms.

Blossoming now,

Tomorrow scattered in the winds,

Such is the flower of life,

So delicate a perfume,

Cannot last long.– Takajiro Onishi, Vice-Admiral, Imperial Japanese Navy, 1944

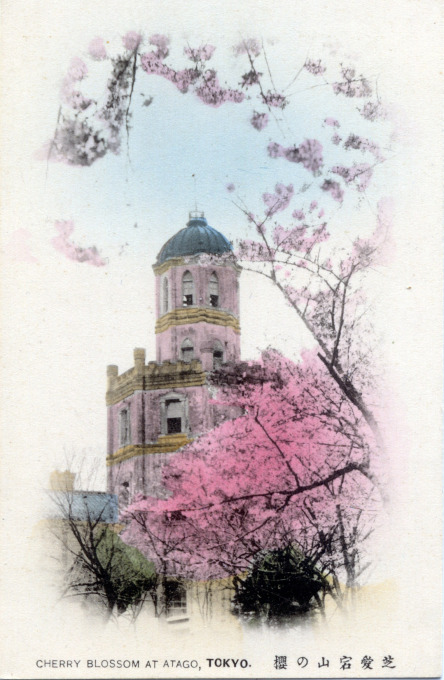

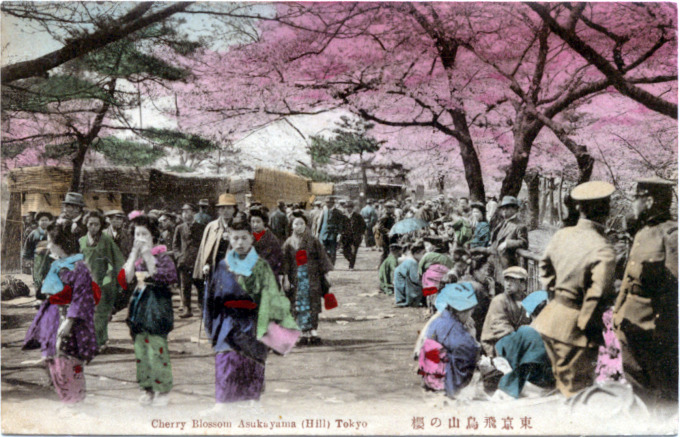

Atago Hill, Asukayama, Koganei, Mukojima, Edogawa & Yoshiwara O-hanami

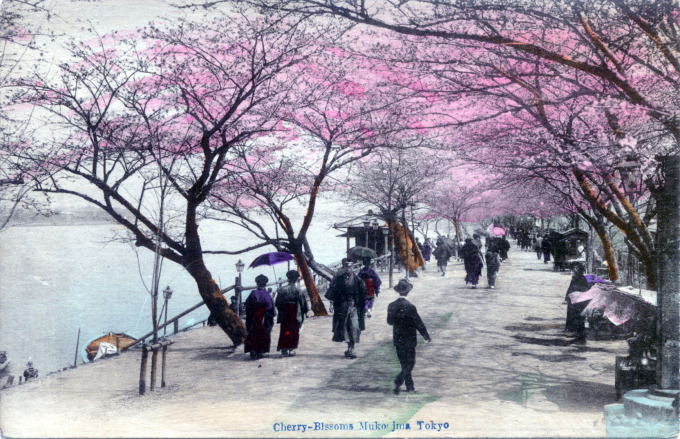

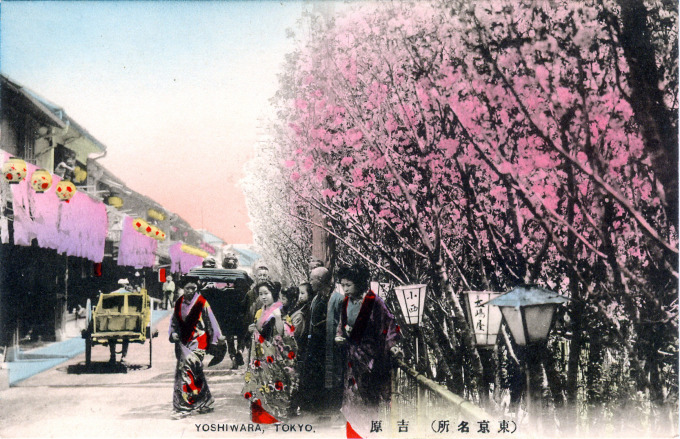

“Cherry-blossoms (Sakura) – Ueno, Mukojima, and Shiba, early in April ; Koganei, middle of April. So many avenues of cherry-trees have been planted in Tokyo during the last twenty years [ca. 1880], that for a brief space in spring the whole city is more or less it show of these lovely blossoms.”

– A Handbook for Travellers in Japan, Basil Hall Chamberlain & W.B. Mason, 1901

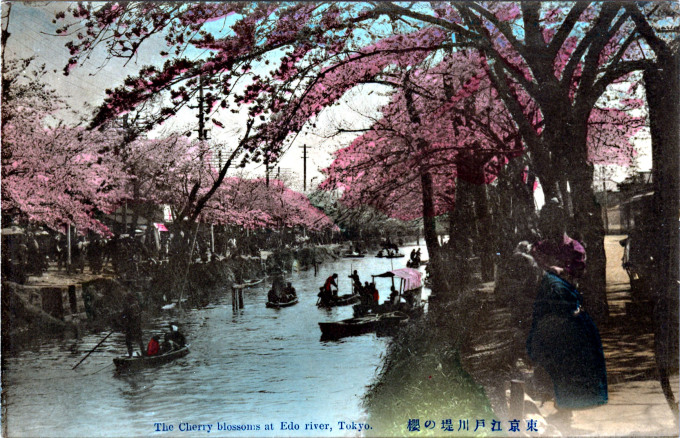

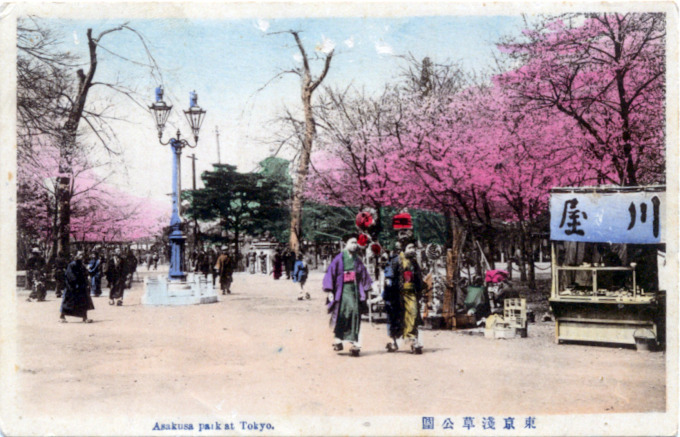

Other popular and scenic turn-of-the-century O-hanami locations included Mukojima, stretching along a picturesque bank of the Sumida River, Shiba Park, and along the canals of urban Edogawa and the not-too-distant rural Koganei in the western suburbs. Smaller clusters of blossoms could also be found at Benkeibashi, and atop Atago and Asuka hills.

- Cherry blossoms at Asukayama, c. 1920.

- Asukayama cherry blossoms, c. 1910.

- Oden [fish cake stew] stand at Koganei, c. 1910.

- Koganei cherry blossoms, c. 1910.

- Mukojima cherry blossoms, along the Sumida River, c. 1910.

- Cherry-Blssoms [sic] Mukojima, Tokyo, c. 1910.

- Cherry blossoms at Edogawa, c. 1910.

- Cherry blossoms at Edogawa, c. 1910.

- Cherry blossoms at Yoshiwara, c. 1910.

- Asakusa Park cherry blossoms, c. 1910.

Pingback: Ueno Park, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Atagoyama (Atago Hill), Tokyo, c. 1910-30. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Koganei Cherry Blossoms, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Children playing under cherry blossoms, c. 1960. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Cherry Blossoms at Mukojima, c. 1910. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo