A couple walk the path around Hibiya Park’s Japanese garden. In the distance, to the west, can be seen the rooftops of the various ministries along Sakuradamon-dori in the neighboring Kasumigaseki government district.

See also:

Hibiya Public Hall, c. 1930

Kasumigaseki (Government District), c. 1910

“In Japan during the Meiji era, as in Europe at the same time, the sense of national unity was stressed as an important moral theme. The state voluntarily used the landscape and its meanings to re-found the national identity. In the plan of Hibiya Koen [park], three essential elements structure the project: a large sport ground, a Japanese garden, and large paths suitable forhorse-drawn carriages.

“The park’s most important space was the grass field in the southwester part; in the original plan called undojo, sport ground … This field provided a space for mass meetings on different occasions, not only sports, but also official celebrations.

“The modern park was clearly meant to contribute to and celebrate a common identity. Rapidly, this ground became used as an urban square for national and official events, and for transgressive uses as well. In 1905, at the end of the Russo-Japanese war, a gathering at Hibiya Park against the peace treaty degenerated into a violent riot in which 300 buildings were destroyed by fire.”

– Performance and Appropriation: Profane Rituals in Gardens and Landscapes, Michel Conan, 2007

Hibiya Park views, c. 1910-1920

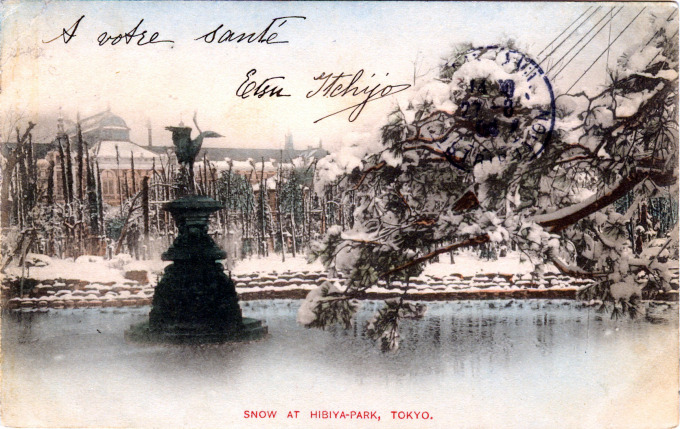

- Snow at Hibiya Park, Tokyo, c. 1910.

- Aviary at Hibiya Park, c. 1910.

- Hibiya Park’s gazebo, c. 1910.

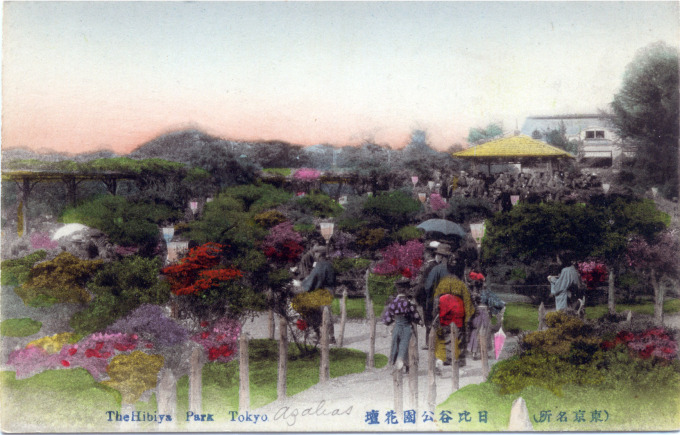

- Viewing azalea’s in the spring, c. 1910.

- Viewing azalea’s in the spring, c. 1910.

- The bronze crane fountain at Hibiya Park, c. 1910.

“Some liked the new park, some did not. Nagai Kafu, on his return from France in 1908, found it repellently formal. It became so favored a trysting place, however, that the Kojimachi police station felt compelled to take action. On the summer night in 1908 when a dozen or so policemen were first sent into the park, they apprehended about the same number of miscreant couples, who were fined.

“Hibya is usually referred to as the first genuinely Western park in the city and in Japan. That is what Kafu disliked about it – he did not think Westernization worked in any thing or person Japanese but himself.

“In fact a good deal of the park is fairly Japanese, and it contains relics of all the eras – trees said to be as old as the city, a fragment of the castle escarpment and moat, a bandstand that was in the original park, a bronze fountain only slightly later.”

– Tokyo from Edo to Showa 1867-1989: The Emergence of the World’s Greatest City, by Edward Seidensticker, 2011

Looking south across the Hibiya Park athletic ground at Hibiya Public Hall, c. 1930.

” Hibiya Park was begun and completed in a wonderfully short time, and, thanks to the skill which Japanese gardeners possess in moving trees, it already has lost its very new appearance. A Japanese gardener will remove a big tree, in bloom, and at any season, and plant it in a new soil, without doing it any apparent injury, and the new trees in Hibiya Park only drooped for a few days and then plucked up heart to- bloom as vigorously as ever.

“I think I am right in saying that the first great occasion on which the park was used for a public demonstration was when the citizens celebrated the safe arrival from Italy of the cruisers Kasuga and Nisshin, which had been bought just before the commencement of hostilities with Russia. There have been many jovial demonstrations since.

“Tokyo has here celebrated all the great victories of the war. It was here that Togo and Oyama were welcomed on their safe return from the scene of battle; it was here that Japanese sailors first learned to fraternise with British tars (there had been a little shyness, I am told, up till then); it was here that the citizens welcomed Prince Arthur of Connaught when he came to bring the Garter for the Emperor.”

– Every-day Japan, by Arthur Lloyd, M.A., 1909

- Geisha posing under an arbor, Hibiya Park, c. 1910.

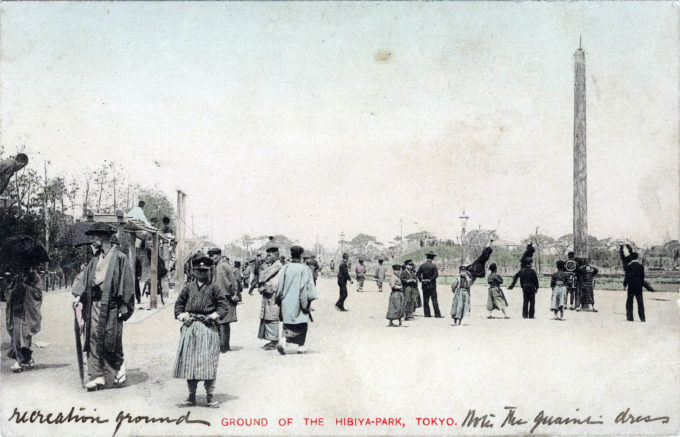

- “Ground of the Hibiya Park”, Tokyo, c. 1910. “Recreation ground. Note the quaint dress.”

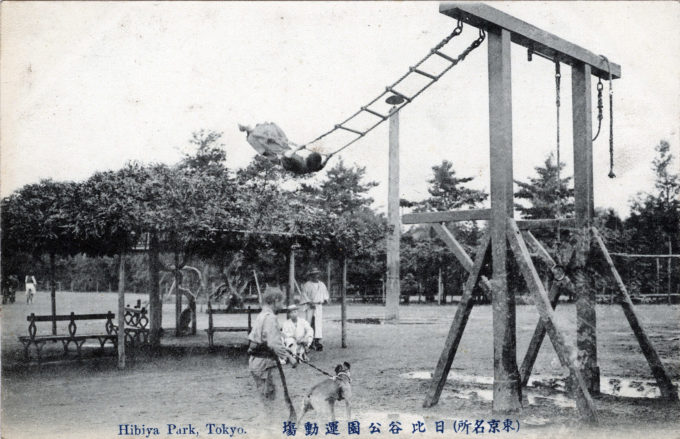

- Hibiya Park playground, c. 1910.

- Playground at Hibiya Park, Tokyo, c. 1910.

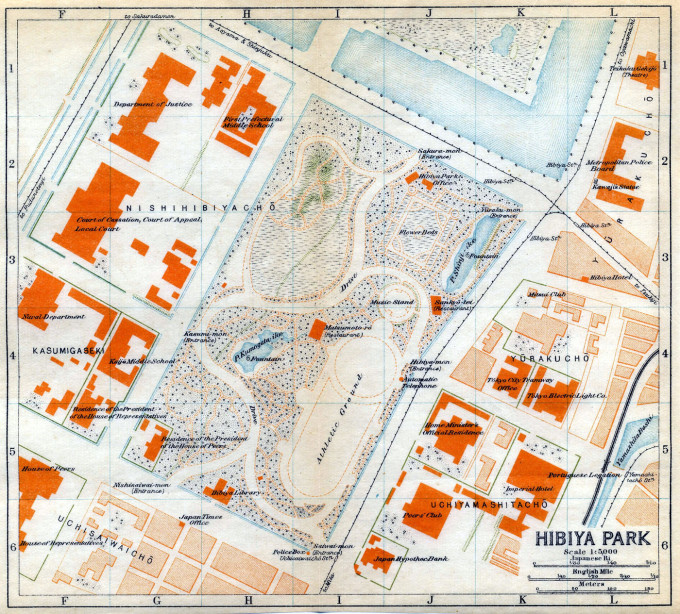

Hibiya Park, c. 1940. Directly across from the park, at right, was located the famous Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Imperial Hotel (1923-1968).

Hibiya-koen [sun match valley park] opened on June 1, 1903. Said to be Japan’s first Western-style park, and viewed as Tokyo’s first proper public park, Hibiya Park was meticulously planned by the national government as yet another display of Japan’s modernization after 1868.

The park grounds were developed from land originally owned by feudal daimyo, the Tokugawa-era provincial lords, whose grand estates occupied the neighborhoods immediately surrounding Edo castle. After the Restoration, the estates were appropriated by the Meiji government, the residences leveled, and the grounds turned over for use by the Imperial army as military drill grounds.

City planners drew up plans to convert the army grounds into the capital’s ministerial and bureaucratic district but were thwarted by the underlying soft subsoil. (The area had once been an inlet of Tokyo Bay but was reclaimed in the 17th century with debris from the Kanda canal project.) The government construction project was then moved slightly west from Hibiya to more solid ground at Kasumigaseki.

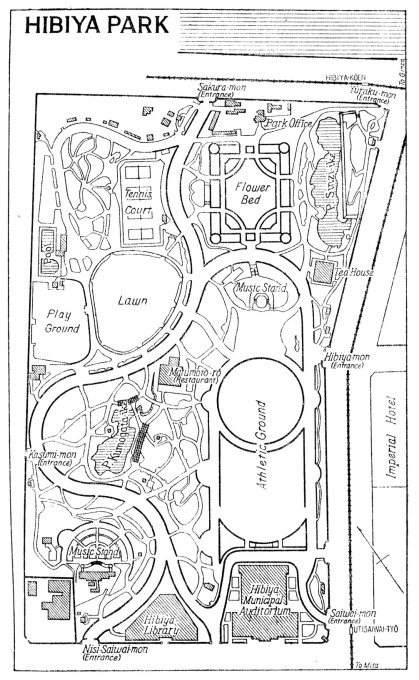

Hibiya Park, c. 1920 in proximity to the Kasumigaseki government district (left) and Yurakucho (right) where the original Imperial Hotel (1890-1923) was sited, on the opposite side of the block where the Wright-designed hotel would be sited (and where the present-day hotel is located). facing the elevated railway instead of Hibiya Park.

Pingback: Akasaka Mitsuke, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Imperial Hotel (1890-1922). | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Hibiya Public Hall (Kokaido), c. 1940. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Tokyo Kaikan, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Azaleas in Hibiya Park, Tokyo, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo