“[A]fter making great efforts to come up to the government standard , we have at last received the coveted recognition for the [girls’] academy. Not yet are we able to get it for the two departments of the college; the Literary College and the Domestic Science Department are still unrecognized.

“You all understand that we get no money from the government, only permission for our high school graduates to enter any school or college, or to enter any examinations for teachers’ licenses. We must next try for recognition for both colleges and then when we secure this our graduates can be granted teachers’ licenses without examination. Now that we have the lesser recognition, we must press on for the greater.

“As a result of our receiving recognition, we are again getting up in numbers. We are now more than one hundred and seventy strong, numbering all departments of the girls’ school. And next year we hope for more, and as soon as we are justified in doing it, we must make great efforts for recognition for the Literary and Domestic Science Colleges.”

– “The Doshisha Girls’ School”, by Mary Denton, Life and Light for Woman, published by the Women’s Board of Missions, January 1912

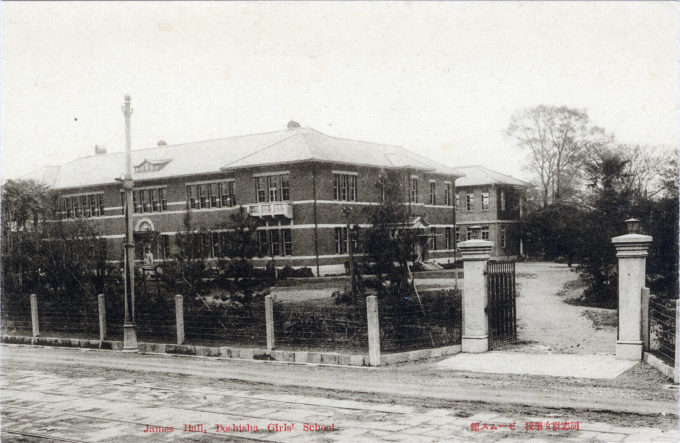

James Hall, Doshisha Girls’ School, Kyoto, c. 1930, founded in 1877 by Niijima Yaeko, wife of Japanese-Protestant missionary and Doshisha University founder Joseph Hardy Niijima (née Niijima Jo). The building was named for Arthur Curtiss James, at one time the largest private owner of railroad stock in the United States. Curtiss was a graduate of Amherst College in Massachusetts – a connection he shared with Yaeko’s husband. James and his wife, Harriet, became benefactors of the girls’ school and of the American Board Missions in Japan after a visit to Japan in 1922.

See also:

Doshisha University, Kyoto, c. 1920.

“Niijima Yae (born Yamamoto Yae), also known as Yamamoto Yaeko, was a Japanese female warrior, educator, nurse and scholar of the late Edo period who lived into the early Shōwa period.

“Skilled in gunnery, she helped defend the Aizu Domain [from the Imperial Army] during the Boshin War, earning Yaeko the nickname of the ‘Bakumatsu Joan of Arc’, defending Aizu-Wakamatsu Castle with her Spencer carbine alongside Aizu warriors. After the surrender of Aizu Domain, she took refuge in nearby Yonezawa Domain in Yonezawa, Yamagata and stayed there for one year.

“Yaeko later served as a nurse during the Russo-Japanese War and Sino-Japanese War, and became the first woman outside of Imperial House of Japan after the Meiji Restoration (1868) to be decorated for her service to the country.

“She was famously known as the wife of Joseph Hardy Niijima (Yaeko converted to Christianity after meeting Joseph), the founder of Doshisha English School – later Doshisha University – in 1875. Yaeko, with the help of the American missionary Alice J. Starkweather, opened a Joshi-juku (young women’s private school) at the former residence of Yanagihara family (a branch of Fujiwara clan) on a site within the grounds of the current Kyoto Gyoen National Garden (Kyoto Imperial Garden).

“In 1877, it was renamed to Doshisha Bunko Nyokoba (Doshisha Branch School for Girls) and soon thereafter renamed to Doshisha Jogakko (Doshisha Girls’ School), and in 1878 it was moved to the current Imadegawa campus into its first self-owned school building built with financial aid from the Women’s Board of Missions for the Pacific.”

– Wikipedia

“Seiwakwan” [Pacific Hall], Doshisha Girls’ School, Kyoto, c. 1930, a gift of the Woman’s Board of Missions for the Pacific and completed in 1919.

“A letter from Miss Denton of the Kyoto Congregational school, written after a visit to Tokyo, indicates the kind of positions which graduates of Christian schools are filling.

‘There are in Tokyo about twenty former students of the Doshisha girls’ school. All are women above the average, of whom we may well be proud. It may be of interest to know what they are doing.

‘Four, as wives of pastors, are doing as much work, perhaps, as their husbands, and another is a real help to her husband in his work as translator of Christian literature. Four are the wives of bankers, three of teachers, and one of a high [government] official. Of the unmarried girls two are in direct Christian work, two in literary work, one studying medicine, another English, one is working in a prominent Christian school, one in the Peeresses’ School, and one in a large kindergarten.’ ”

– The Education of Women in Japan, by Margaret E. Burton, 1914