Main gate entrance, Yokosuka Naval Base, c. 1949. It was not until the beginning of the Korean War in 1950 that the former Imperial Japanese Navy base began its transformation into a strategic base for the US 7th Fleet. Before then, during the early Occupation era, Yokosuka was an almost-sleepy backwater port for the US Navy, serving primarily as a Marine Barracks, a naval hospital, and a ship repair & maintenance facility for the US fleet in the Pacific.

See also:

Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, c. 1910.

Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, 1936.

“With respect to the allegation that the former Japanese naval base at Yokosuka is being converted into a modern naval base, it may be stated categorically that this is not true. This base has been used from the beginning of the occupation by the United States naval forces supporting the objectives of the occupation – which it is both necessary and proper for them to do. Accordingly, the implication that the Far Eastern Commission decision on the Basic Post-Surrender Policy for Japan is being violated is wholly without foundation.”

– Memorandum by the Assistant Secretary of State for Occupied Areas (Charles Saltzman) to the United States Representative on the Far Eastern Commission (Major General Frank R. McCoy), November 4, 1948

The Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (Christopher Mayhew, 1946-1950) [in testimony before the House of Commons, 10 Nov 1948]: “The former Japanese naval base at Yokosuka has been used since the beginning of the occupation by the naval forces operating in support of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Japan. I am informed that there is no truth in reports that Yokosuka has been converted into a modern naval base, and that such limited modifications as have been made there have been solely for the purpose of maintaining the efficiency of the United States naval vessels and for servicing visiting ships.

“His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom are fully satisfied that there has been no breach of the existing policies regarding the disarmament and demilitarisation of Japan and no special instructions have been issued to our representative on the Far Eastern Commission.”

The best known Commander of Fleet Activities at Yokosuka was the one who served there the longest: Captain Benton W. ‘Benny’ Decker [see below], who was in charge from April 1946 until June 1950. When he assumed command, Captain Decker and his staff were able to devote their time to helping the townspeople economically, politically and socially. Buildings which had once housed war equipment were converted into schools, churches and hospitals for the people of Japan.

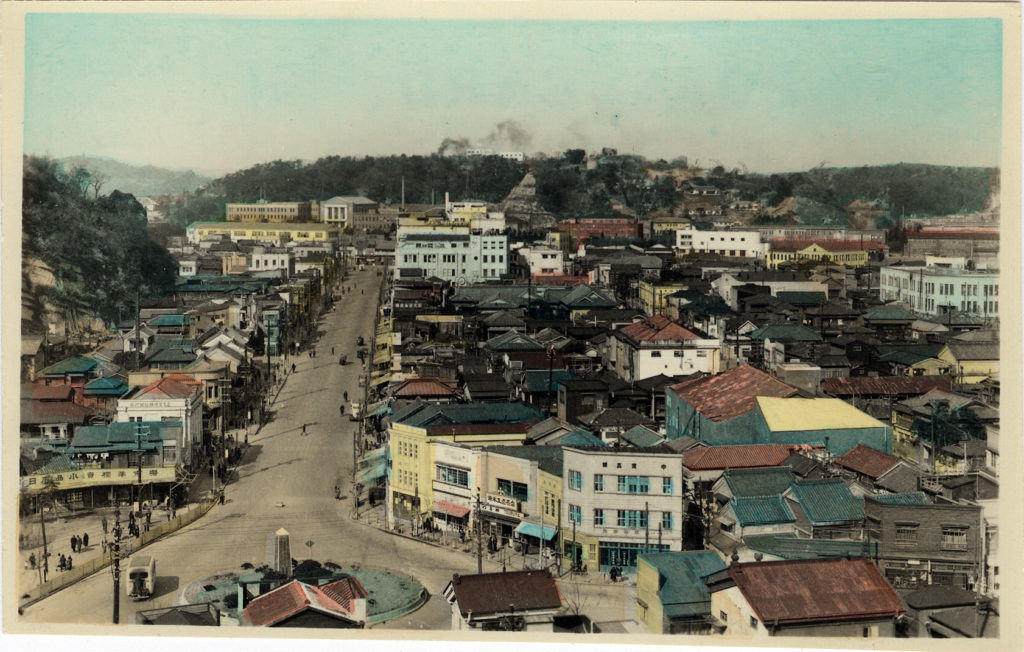

- Yokosuka City, aerial view, c. 1949.

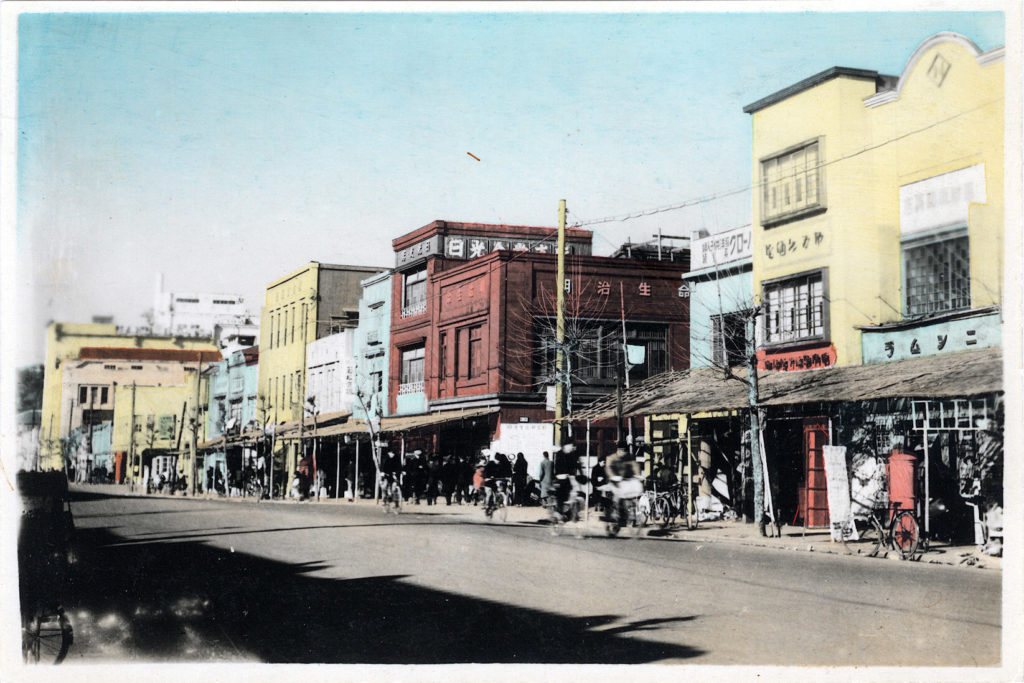

- Yokosuka City, street view, c. 1949.

“Before the occupation, the Japanese naval base of Yokosuka, ten miles south of Yokohama, was a huge secret armament center, a forbidden city surrounded by an eight-foot wall. For 26 years, no foreigner had been permitted inside it. The mysterious city symbolized authority-ridden, feudal Japan.

“Today, Yokosuka is a pilot plant for democracy. Its citizens elect their own officials, have formed Japan’s first postwar Red Cross, a Parent-Teachers Association, and the largest women’s club in the world.

“The man chiefly responsible is Captain Benton Weaver Decker, USN. Captain Decker fought most of the war in the South Pacific, emerging as skipper of the battleship Maryland. When he arrived at Yokosuka in June 1946 he found what had become the most important U.S. naval base in the Far East shockingly inefficient and demoralized. A freight car on the base was the happy home of a number of sailors and their Japanese girl friends. They were coining money on the black market by selling electric coffee pots, radios, sleeping bags and other goods from the navy exchange (BX). One steward in a single deal had sold a ton of sugar stolen from the officers’ mess.

“Although the success of the base depended largely on the cooperation of thousands of Japanese workers, garish American posters depicted ferocious, buck-toothed Japanese soldiers with swords drawn. Officers cursed Japanese to their faces, arrogantly race through crowded city streets with sirens roaring. The Japanese community was demoralized by suffering and starvation. Thousands of civilians prowled the streets. Sanitary conditions were appalling; there was no sewage system; clouds of flies blackened the skies; deserted buildings were infested with rats. Patients with contagious diseases filled the hospital wards. Cholera and typhus were common.

“Decker went in with fists flying. ‘This isn’t a U.S. Navy base; it’s a junk pile!’ he roared, at a general staff meeting. ‘We want a taut ship.’ Decker separated the sailors from their shacks and sweethearts. He tore down offensive posters. He arranged to have fliers spray the city with DDT. Seamen demolished rotten, rat-infested buildings. The lumber was dumped in a vacant lot where the Japanese lined up by the thousands to collect firewood for the cold winter months.

“… Decker knew that the city’s good health depended ultimately upon its economic well-being. Scattered over the naval base were scores of deserted buildings which once housed armament machinery. Japanese businessmen were invited to make proposals for the use of the buildings. Many of them are now thriving factories turning out products desperately needed by the Japanese.

‘… More than 80 new peacetime industries have come to Yokosuka – among them a furniture factory, a pulp paper plant, a whale-processing industry, seven textile factories, a glass works, a bicycle assembly plant, two sawmills and a food refrigeration plant. Helping rebuild Japan, they also reduce the cost of occupation for the United States.

‘… Recently, when word got around that the Captain might be sent off on a tour of duty elsewhere, the Yokosuka Municipal Assembly petitioned General MacArthur to permit Captain Decker, ‘adored and respected by each citizen of Yokosuka,’ to remain ‘for the sake of the city’s progress.’ A committee called on Decker. ‘In case you are not retained,,’ said the spokesman, ‘we want you to resign from the Navy, become a Japanese citizen and run for mayor.'”

– “Adored By Each Citizen of Yokosuka”, by Blake Clark, The Reader’s Digest, September 1948

Enlisted Men’s Club, Yokosuka Naval Base, c. 1949. From around 1947 to 1980, Club Alliance was the largest U.S. Navy enlisted club in the world. Some sources say that before the end of the war it was an IJN enlisted club. The club was located in the city of Yokosuka about one quarter mile from the main gate of the Yokosuka Navy Base. Sometime in the early 1980’s, the Club Alliance was returned to Japan. It is now the site of a large department store.

During the 20-th century, the base at Yokosuka became one of the most important facilities of the Imperial Japanese Navy. It is the place where some of the most famous Japanese machines were built, including Yamashiro, Shokaku or Hiryu. These are just some of the names that scared the entire world during World War II. The base reached its peak during that war. It was a very crowded place. More than 40,000 inhabitants were working on 1,1 square kilometers.

In the summer of 1945, the base officials surrendered in front of the American forces. The base was taken over by the US Marines, the US Navy and the British forces. In the end, only the US Navy remained on site. Soon after being taken over, the installation was renamed to Fleet Activities Yokosuka. Some of the facilities on site were modified according to the Americans’ needs.