See also:

How Faubion Bowers saved Kabuki, c. 1950

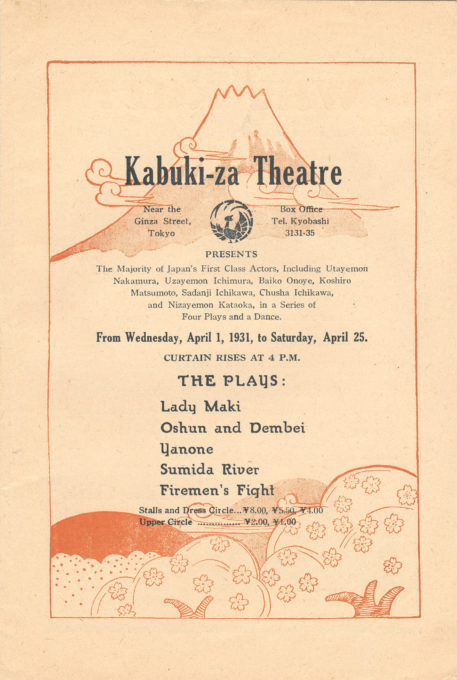

Kabuki Theatre, Tokyo, 1911-1951.

“The Japanese theater is the only place left in which one can study the ways of Old Japan. Though it retains many of the ancient and grotesque traditions of its early days, it is accurate in presenting customs that else long since would have passed from memory. Its language, too, is formal and archaic, and the intonation of the actors almost terrible. You will not find such language or such voices anywhere off the stage.

“A half-minute’s attempt to imitate the sounds the native actors produce would give a Westerner bronchitis. The throat is contracted, the veins swell, and the blood seems ready to burst from every pore of the tragedian’s face. Then the eyes roll, individually and independently, one up, the other down, one to the east and the other to the west, or only one gyrates and the other rolls, until only the white shows.”

– The Heart of Japan: Glimpses of Life and Nature Far from the Travellers’ Track in the Land of the Rising Sun, by Clarence Ludlow Brownell, 1903

As theater, Kabuki [song dance skill] is best-known to many Westerners for its reliance on male actors for the portraiture of both male and female roles [onnagata (woman form alternative)]. The term Kabuki itself is formed of three words — ka [song], bu [dance] and ki [skill] — and is a literal description of its stage form.

Opposite the aristocratic appeal of Noh, Kabuki was a ‘peoples’ drama.’ Considered to be avant-garde at its beginnings (and, hence, morally corrupt according to feudal Tokugawa culture), Kabuki borrowed much from Japan’s puppet theater traditions: its plays, stagings, costumes and even puppet-ish movements. Like Western opera, much dialogue is given with musical accompaniment; Kabuki orchestras [debayashi] consist of various percussion instruments (including taiko [drum]), a Noh flute, samisen [three-stringed banjo], and shakuhachi [bamboo flute].

“So it was a play with very few actors. Nevertheless, when I think of it now, I feel as if there has never been such a great Kabuki … I watched it from a corner near the hanamichi of the great Kabuki-za, so I saw the hanamichi right in front of me. In time the play began, and a mysterious person emerged on the hanamichi.

“It was Lady Kaoyo. Lady Kaoyo comes out barefoot, that’s the rule; she isn’t supposed to wear tabi socks. For some reason she must come out barefoot; it’s always been that way. So the barefoot Lady Kaoyo passed right before my eyes. And the feet were all wrinkled. And you couldn’t imagine that she was the beauty who would touch off the event called Chushingura. Besides, she suddenly voiced an utterance, and I was shocked. How could a man utter such a voice; I was simply amazed as I watched.

“And I think, though I was still a young boy, I felt that Kabuki had an indescribably mysterious flavor. Like the dried fish of Kusaya, it has a strong smell but has a strangely delicious taste.”

– My Friend Hitler and Other Plays of Yukio Mishima, Yukio Mishima, 1956

Daijo (opening act) of the famous Kabuki play “Kanadehon hushingura” [“The Treasury of Loyal Retainers”], c. 1910, one of the most important plays in the Kabuki repertoire, a retelling of the story of the Forty-seven Ronin (masterless samurai) first performed in 1748. The opening part of the first act of a jidaimono [historical dram] is called daijo. Solemn and ceremonial daijo scenes such as the above are used for the beginning of long, large-scale plays.

“It was a woman, O-Kuni, who founded the popular stage in Japan, some time in the year 1596. She was a sacred dancer before the great Shinto shrine of Izumo.

“Being drawn to Kyoto, the capital and the most populous city of the land at that time, she seized the opportunity to set up a platform on the dry bed of the River Kamo, where she performed her half Buddhist, half Shinto dance. A handsome Samurai, Nagoya Sansaburo, having stood among the crowd to watch what must have been an unusual proceeding for a female at the time, made her acquaintance and they fell in love. Sansaburo soon changed her simple semi-religious entertainment into something more popular. She appeared in male apparel, two swords thrust through her belt, and all Kyoto flocked to see the novel entertainment.

“Later companies of women were formed, but gradually men joined the ranks, and when the players became mixed their morals were anything but satisfactory, and the government stepped in and prohibited women from appearing upon the stage … Deprived of women the male performers were forced to develop the specialty of onnagata, or women’s roles. These impersonators of women became so fascinating that again the authorities became active and put a ban on the onnagata.”

– “The Stage of Today in Japan”, by Zoe Kincaid, Japan Magazine of Overseas Travel, January 1927

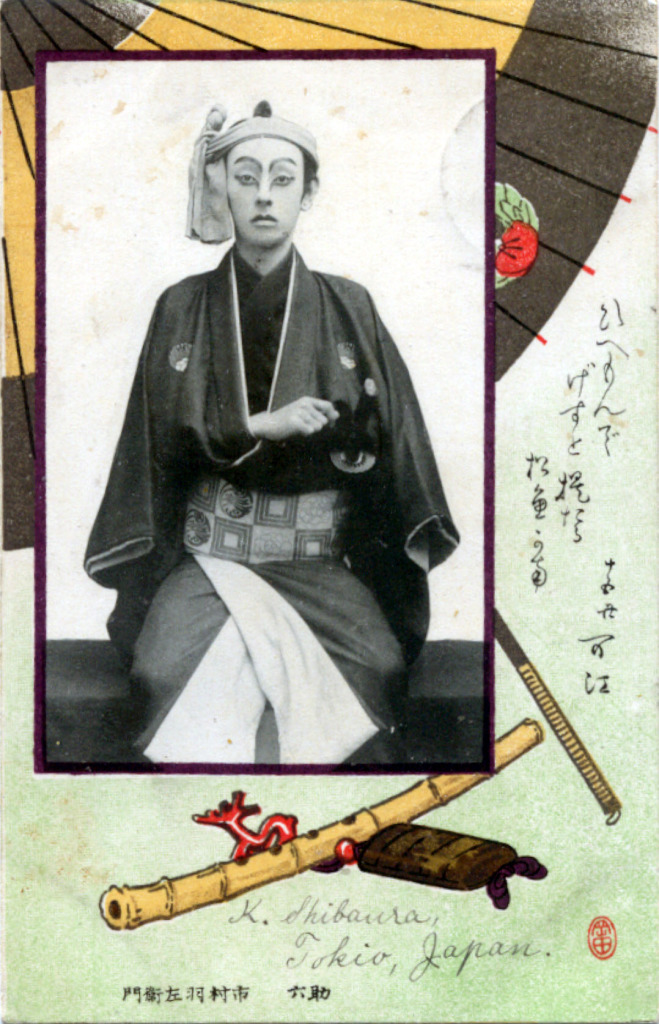

- Kabuki actor Ichimura Uzaemon XIV (aka Bandō Kakitsu I), c. 1910.

- Kabuki onnagata actor, Nakamura Shikan V (aka Nakamura Fukusuke IV), c. 1910.

From the wiki: “Important elements of kabuki include the ‘mie‘, in which the actor holds a picturesque pose to establish his character. At this point his house name [yago] is sometimes heard in loud shout [kakegoe] from an expert audience member, serving both to express and enhance the audience’s appreciation of the actor’s achievement. An even greater compliment can be paid by shouting the name of the actor’s father.

“Kabuki’s highly lyrical plays are regarded, with notable exceptions, less as literature than as vehicles for actors to demonstrate their enormous range of skills in visual and vocal performance. These actors have carried the traditions of Kabuki from one generation to the next with only slight alterations. Many of them trace their ancestry and performing styles to the earliest Kabuki actors and add a ‘generation number’ after their names to indicate their place in the long line of actors.

“Traditionally, a constant interplay between the actors and the spectators took place in the Kabuki theater. The actors frequently interrupted the play to address the crowd, and the latter responded with appropriate praise or clapped their hands according to a prescribed formula. They also could call out the names of their favorite actors in the course of the performance.

“Because Kabuki programs ran from morning to evening and many spectators often attended for only a single play or scene, there was a constant coming and going in the theater. At mealtimes food was served to the viewers. The programs incorporated themes and customs that reflected the four seasons or inserted material derived from contemporary events.

“During its first two decades, dating from 1603, females — not males — performed all roles. Priggish Tokugawa authorities banned female performers from Kabuki roles in 1629, then displaced Kabuki troupes entirely out of the Edo administrative districts into more distant, less accessible locales including Asakusa. The ban was lifted in 1879 by Meiji reformers but, by then, onnagata had become so thoroughly identified with, and ingrained into, Kabuki tradition that female impersonation remained de rigeur even after the ban was lifted.”

Pingback: Kabuki Theatre, Tokyo. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: View of the stage and interior, Kabukiza, Tokyo, c. 1960. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: How Faubion Bowers Saved Kabuki. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: The 47 Ronin (Genroku Ako Vendetta). | Old TokyoOld Tokyo