“The festival of O-Bon has come, and along the city streets are kindled fires to light the returning spirits to their homes; on every porch and balcony are hung lanterns, glowing balls of light, some with long streamers that wave and flutter in the breeze, or bits of glass that tinkle as if ghostly hands were making music.

“And in every home, before the ancestral tablets are set special offerings of fruits and fresh vegetables; while in the graveyards, tombs are cleared from moss, newly served with food and drink, and decorated with lanterns.”

– In the Land of the Gods: Some Stories of Japan, by Alice Mabel, 1905

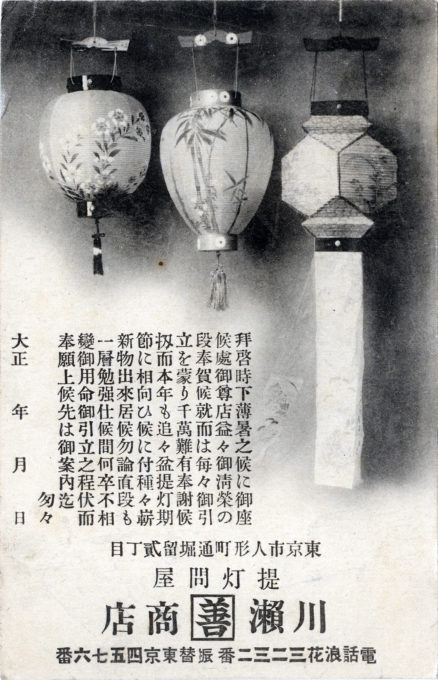

“We are proud to be the Best of the Best”, Kawase Zen Shouten [Kawase ‘goodness shop’] O-bon chochin paper lantern advertising postcard, Ningyocho, Tokyo, c. 1925. The annual Feast of the Dead, or O-bon matsuri, is celebrated at the August full moon. For three days the spirits of the dead are believed to revisit their old homes, and special rituals are performed for their benefit and entertainment.

See also:

Japanese Lanterns (Chochin).

“As the legends vividly illustrate, and as Yanagita Kunio pointed out in his influential book, About Our Ancestors, the traditional Japanese world of the dead lies not far from the world of the living, and the souls of departed relatives remain among the survivors, or at least close enough to visit the family during Obon season, for example. Also their world, the world of the dead, remains ‘alive,’ even after death in this world has occurred.

“This attitude toward death, and human relationships with those who have passed on to the other world, is originally based on neither Neo-Confucianism nor Buddhism, but rather on the much earlier ‘ancestor cult’ (or ‘ancestor complex,’ as Professor Yamashita Shinji has more recently called it). This Shinto-based ancestor complex, which had already been in place for a thousand years by the time of the Tokugawa era, characterizes the whole Japanese social structure, even if it is not consciously recognized or intellectually articulated.

“… In addition to the specific funerals and memorials celebrated by a family for particular individuals on this increasingly complex calendar, there is the annual observance of Obon, when all the deceased members of a family or community are entertained with feasting and dancing. Observed nowadays in August, the Obon, or Urabon Festival, was originally celebrated on the fifteenth of July on the older lunar calendar. On the first day of the festival, according to Japanese belief, the souls of the dead come back to visit their homes and families for two or three days.

“Although practically everyone celebrates Obon to some extent, those families who have lost someone during the current year are especially involved in the preparations and festivities. On the first evening of the festival, a small fire is lit in the yard to light the way for the souls on their way home. People without a yard will light a candle, or perhaps some wood chips by the front door of the house; in some places, fires are ignited on nearby mountains.

“In older times, people lit torches or lanterns all the way from the cemetery or the nearby mountains (where spirits are also thought to dwell) to their homes. An altar in the home is decorated with various offerings of food and flowers, as well as straw figures of horses and cattle, to honor not only the family’s dead souls, but those of others who no longer have relatives in the vicinity. Offerings are placed before the tablets with ancestors’ names which stand on the family altar.

“Sutras may be read and other prayers offered. In many communities, a particular dance is performed, usually with everyone joining in. The bon-odori, performed during evening hours, is a dance which has developed from (or in conjunction with) the medieval nenbutsu-odori (literally, Buddha-invocation dance), and each locale has developed its own particular set of tunes and distinctive dance steps.

“On the third day of Obon, the families send their spirit relations back to the “other side” with farewell fires, often in the form of small lanterns which are allowed to float down a river or away on an outgoing tide. The fires are believed to accompany the souls back to the world of the dead and oblige them to go.”

– Ghosts and the Japanese: Cultural Experience in Japanese Death Legends, by Michiko Iwasaka & Berre Toelken, 1994