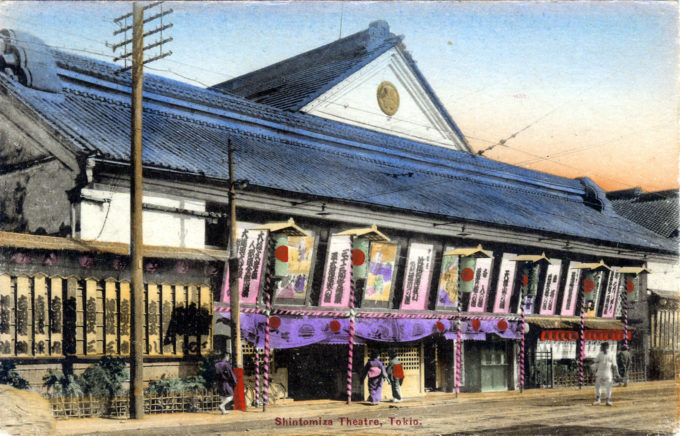

Shintomi-za Theatre (the former Morita-za), Tokyo, c. 1920, constructed in 1878, replaced an earlier kabuki venue that burned down in 1876. Shintomi-za preceded the arrival of its more famous counterpart, Kabuki-za, by over a decade.

See also:

Kabuki Theatre, Tokyo, 1911-1950

“The great theatre of Tokio is the Shintomiza, a long, gabled building, ornamented above the row of entrance doors by pictures of scenes from the play. The street is lined with tea-houses, or restaurants, for a play is not a hap-hazard two-hour after-dinner incident. A man goes for the day, carefully making up his theatre party beforehand, the plays generally beginning at eleven o’clock in the morning, and ending at eight or nine in the evening.

“… Theatre buildings are light and flimsy wooden structures, with straw-mats and matting everywhere. They are all alike — a square auditorium with a sloping floor, a single low gallery, and a stage the full width of the house. The floor space is divided into so-called boxes by low railings, that serve as bridges for the occupants to pass in and out. Visitors always sit on the floor, each box being six feet square and designed for four people … Within the building are booths for the sale of fruits, tea, sweets, tobacco, toys, hair-pins, photographs of the stars, and other notions, so that a box-party need not leave the house in pursuit of any creature comforts. The ventilation is too good, and the light and open construction invites wintry draughts.

“There is always a drop-curtain, generally ornamented with a gigantic character or solitary symbol, and often nowadays covered with picturesque advertisements. Formerly, so much of the play was given by day that no foot lights and few lamps were used … With the adoption of kerosene the stage was sufficiently lighted, and the Shintomiza has a full row of footlights, while the use of electricity will soon be general.

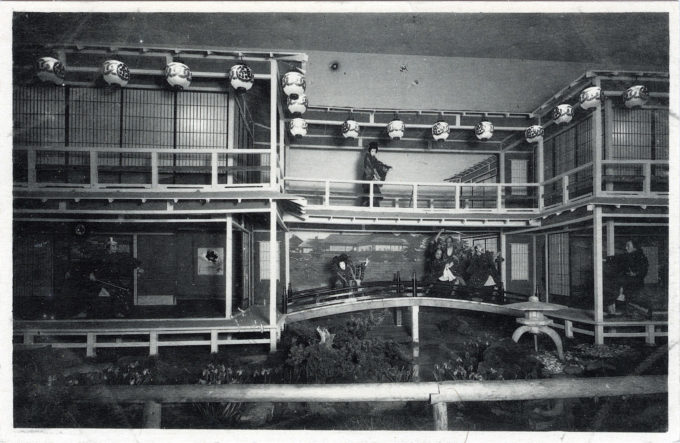

“The miniature scale of things Japanese makes it possible to fill a real scene with life-like details. The stage is always large enough for three or four actual houses to be set as a front. The hana michi is sufficiently broad for jinrikishas, Kagos, and pack-horses, and with the illumination of daylight the unreality of the picture vanishes, and the spectator seems to be looking from some tea-house balcony on an every-day street scene.

“Garden, forest, and landscape effects are made by using potted trees, and shrubs uprooted for transplanting. The ever ready bamboo is at hand and the tall dragon-grass, and the scene-painters produce extraordinary illusions in the backgrounds and wings. Some of the finest stage pictures I have seen were in Japan, and its stage ghosts, demons, and goblins would be impossible elsewhere.”

– Jinrikisha Days in Japan, by Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, 1891

“From the year 1842 through the early Meiji Period Saruwaka-cho in Asakusa was the center of Edo drama, but the ‘Three Theatres of Edo’ – the Morita-za, Nakamura-za and Ichimura-za – featured surprisingly primitive architecture. Even such new theatres of the Meiji Era as the Saruawak-za and the Shintomi-za showed only preliminary breaks with the earlier architecture. It was not, indeed, until Western drama became popular in Japan that the styles of theatrical architecture were to change radically.

“The Morita-za had moved from Asakusa to central Tokyo in 1872, and in 1875 changed its name to the Shintomi-za. The theatre burned down, however, in the following year and the new building, completed in 1878, proved an excellent example of the new trends in Kabuki architecture. As is true with much of the Westernization of Japan, it was the conveniences of Western architecture that were first adopted, and the use of gas lamps in illumination, for example, was to have its effect upon methods of staging.

“The new theatre opened with the Kabuki actors appearing in trousers and swallow-tailed coats, the Army and Navy bands performing, and eminent persons from all quarters present at the premiere. Other Tokyo theatres soon followed the lead of the Shintomi-za in renovating their appearances, but the changes were largely superficial, and it was not until the theatre reform movement arose that authentic Western-style architecture was to appear in the theatrical world.”

– “Early Meiji Architecture, 1868-1885”, Japanese Arts and Crafts in the Meiji Era, edited by Naoteru Uyeno (trans. by Richard Lane), 1958