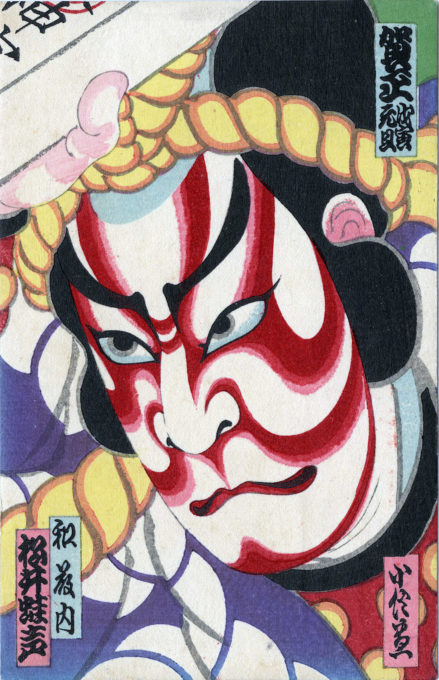

Kabuki stage makeup (kumadori), c. 1930. A postcard reproduction of a kabuki performance poster. Sujiguma is one variety of almost a dozen kabuki makeup techniques (suji, face; guma/kuma, shading), this one used for roles featuring heroes of super-human strength, filled with intense anger. Red kuma are drawn sweeping upwards over the lines of the face. A triangle in red is added on the chin; black ink is drawn on the corners of the mouth.

“Kumadori stylistically beautifies and emphasizes the stereotypical personality of a specific role. At the same time, unlike the Noh masks or the Chinese stage makeup used in Peking Opera, the kumadori allows for greater power of expression since it closely follows the actual facial features and expressions of the actor.”

– Toshiro Morita, Kumadori, 1985

“The use of transformational makeup in Japan can be traced back to ancient religious rituals and, over time, as such ceremonies evolved into theatre, makeup was retained as a vehicle for transforming the actor in performances maintaining elements of the ritual origins without the specific religious context.

“We can glimpse a direct link between the famous makeup for the samurai hero of the Aragato style of Kabuki and the ancient use of makeup in rituals pertaining to spirit worship and shamanic possession, for the samurai’s ability to do the impossible is understood to be because they have allowed themselves to be possessed by a powerful kami (‘supernatural deity’) and thus have become hitokami (‘man-gods’) and a functionality of any extravagant transformational makeup like this is to generate the suspension of disbelief in the audience so that they can accept the convention that they are in the presence of supernatural beings during the performance

“In the Edo region of Japan in 1673, a fourteen-year-old actor named Ichikawa-Danjuro I invented a kabuki performance style called the aragato, or the ‘wild show’ … and for his first performance he painted his face in a bold red and black makeup design—a modern example of which is at the top of the post, this suji-kuma or ‘sinew pattern’ worn by the samurai hero of one of the aragato dramas as it is seen today. (And, to be clear, real samurai did not paint their faces — this is an actor’s invention to project the inherent power of the character he portrayed) The complex stylized makeup in aragato kabuki is called ‘Kumadori’.

– Kumadori – The Painted Faces of Japanese Kabuki Theatre, by Christopher Agostino, January 2020

Pingback: “Year of the Tiger”, New Year’s postcard, 1938. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo