“[T]here were winds of change blowing with regard to the operational concepts within Imperial Army Aviation in 1934. Concepts were introduced to attach more importance to offensive counterair than to a strictly ground support-centered mission.

“For the first time, the Imperial Army adopted the idea of ‘aerial exterminating action’ in the ‘Airman Drill Book’ compiled as an ‘airbattle standard for air units.’

“The manual still placed reconnaissance and close air support as the main missions of air units, but [now] prescribed that ‘aerial exterminating action’ must be the means to assist ground forces to reach a successful position.'”

– British and Japanese Military Leadership in the Far Eastern War, 1941-45, edited by Brian Bond and Kyoichi Tachikawa, 2004

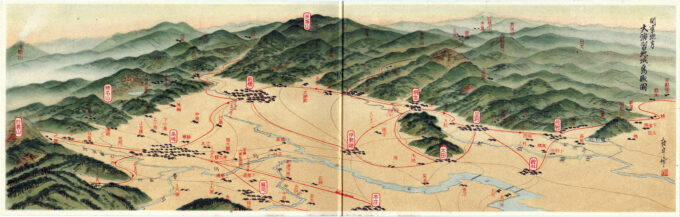

Special Military Exercises propaganda postcard, Kanto Plain, Tokyo, 1934. A panoramic view of the large-scale Imperial army military exercise held in the autumn of 1934 northwest of Tokyo between Kumagaya and Takasaki/Maebashi (Tokyo City would be located just off the image lower-right) and observed by the Emperor. The exercises, held from November 10-18, 1934, involved for the first time a significant deployment of troops and equipment (seven armies and a major portion of the empire’s naval and army air forces), simulating real-world logistics and battlefield conditions, and testing coordination between different branches of the Japanese military.

See also:

“Life in the Army” series, IJAAS parade field fly-over, c. 1914.

Grand Fleet Review, Osaka-Kobe, 1930.

Imperial Japanese Army conscripts began basic training every year in January, progressed through squad and platoon drills across spring and summer and by October–November were participating in large-scale regimental or divisional exercises — commonly referred to as ‘Autumn Maneuvers’.

In November 1934, the Imperial Japanese Army staged a high-profile, Emperor-observed ‘Special Grand Maneuver’ (Tokubetsu Dai-Enshū). This “grand maneuver” consolidated the usual annual exercise into a larger and more formalized demonstration with the additional attendance of the Emperor.

The late autumn maneuvers involved tens of thousands of infantry and horses across the Gunma/Tochigi/Ibaraki/Saitama prefectures under the Emperor’s eye. The mass rehearsal validated General Staff Headquarters planning for calling up reservists, timetabling trains, and running road/rail traffic control over a densely settled region — procedures the Army then reused when staging divisions for China after 1937 for actual combat, principally:

- Rail-based mass mobilization, followed by light, horse-dependent logistics, and fast infantry movements.

- Tactical emphasis on encirclement, night operations, and maintaining a warrior spirit consistent with seishin kyoiku (the spiritual conditioning of troops).

Those strengths enabled quick early campaigns. After 1937, the Army advanced along Chinese railways, building forward depots near rail-heads and pushing supplies ahead by divisional transport regiments and requisitioned local lift—textbook IJA practice.

In the Malaya Campaign (1941–42), Japanese forces again relied on light loads and expedients (notably bicycles) to outrun opponents on the road — another expression of the same ‘move fast with modest logistics’ mindset honed in peacetime maneuvers.

But, the same choices later became liabilities when distance, terrain, and enemy interdiction outgrew what rail-heads, horses, and light scales could support. When thrust into real-world large-scale combat engagements — as at Lake Khasan (1938) and Nomonhan/Khalkhin Gol (1939) against the U.S.S.R. army — the I.J.A. was taught harsh lessons.

The General Staff realized too late that their foot soldier, light-logistics doctrine, stressed in these exercises, was vulnerable against Soviet heavy mechanization and superior artillery, and the Russian attack vs. support (Japanese) armor doctrine.

- Special Military Exercises commemorative postcard, Kanto Plain, Tokyo, 1934. In the foreground is a Type 89 Chi-Ro medium tank, newly deployed by the I.J.A. in support of infantry.

- Special Military Exercises commemorative postcard, Kanto Plain, Tokyo, 1934. General Staff viewing the exercise from the field headquarters.

- Army Special Grand Maneuver for the Emperor, 1934. The imperial standard (Tennō-ki), a gold 16-petal chrysanthemum centered on a red background, is displayed ahead of Emperor Hirohito’s procession past a bevy of local officials.

- Army Special Grand Maneuver for the Emperor, 1934. Emperor Hirohito, left facing table, reviews the Grand Maneuver campaign map at the Hitotsuyama field headquarters.