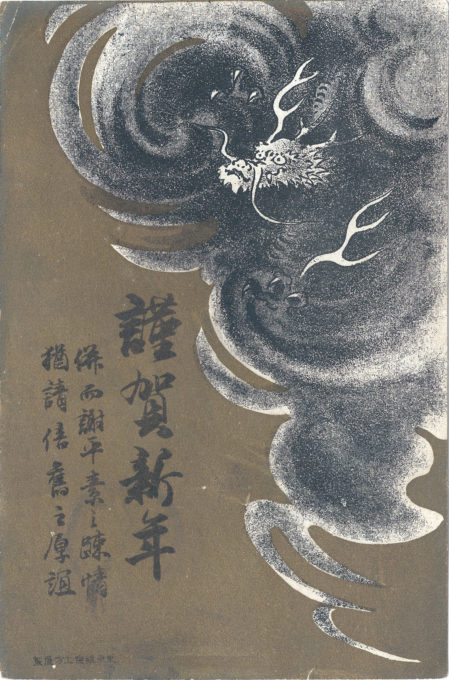

- “Year of the Dragon”, New Year’s postcard, 1916.

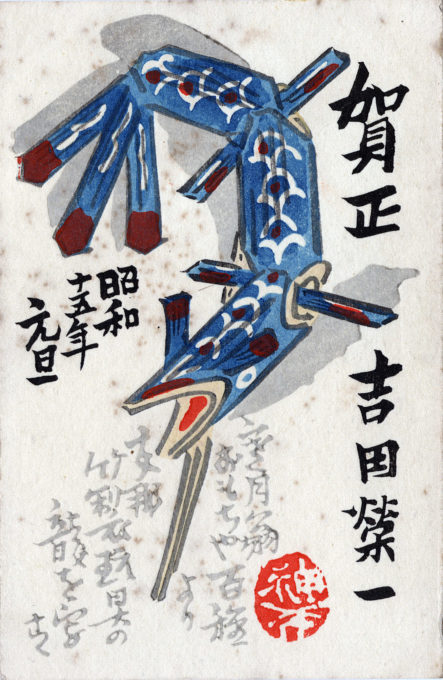

- “Year of the Dragon”, New Year’s postcard, 1940.

People born in the year of the Dragon are the most complicated of all the 12 signs of the Zodiac cycle. They are excitable, short-tempered and stubborn. However, they are also honest, sensitive, and brave and can inspire trust in most anyone.

Born 2024, 2012, 2000, 1988, 1976, 1964, 1952, 1940, 1928, 1916, 1904.

See also:

Akemashite Omedetou, Happy New Year, c. 1910

Dezome-shiki, New Year’s Day, c. 1960

Akasaka Mitsuke, New Year’s Greetings, 1909

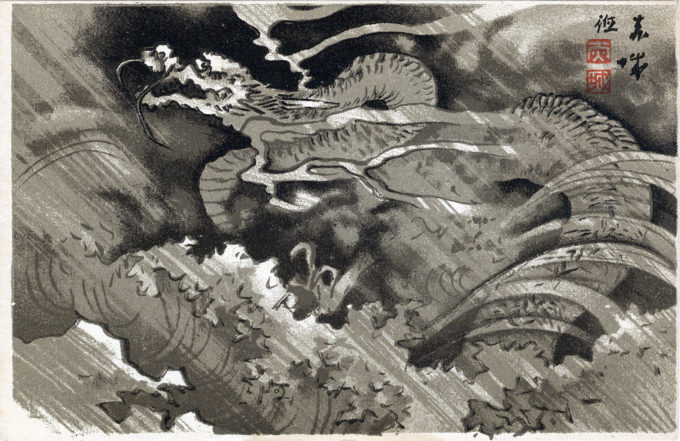

“Chief among ideal creatures in Japan is the dragon. The word dragon stands for a genus of which there are several species and varieties. To describe them in full, and to recount minutely the ideas held by the Japanese rustics concerning them, would be to compile an octavo work on dragonology.

“In the country itself, the monster is well nigh omnipresent. In the carvings on tombs, temples, dwellings, and shops – on the Government documents, printed on the old and the new paper money, and stamped on the new coins – in pictures and books, on musical instruments, in high-relief on bronzes, and cut in stone, metal, and wood – the dragon (tatsu) everywhere ‘swinge the scaly horror of his folded tail,’ whisks his long mustaches, or glares with his terrible eyes. The dragon is the only animal in modern Japan that wears hairy ornaments on the upper lip.

“… The fact that the first born among a litter of dragons is a happy creature, and delights in harmonious sounds, accounts for the fact that the tops of most temple bells are cast in the form of a curved dragon, thus serving tho double purpose of pleasing the dragon tribe and providing ears to hang the bell by. The 2nd of the litter of 9 which the dragoness produces at parturition delights in the sounds of musical instruments, hence the koto, or horizontal harp, and the tsuzumi, or girl’s drum, struck by the fingers, are ornamented with the figure of the dragon.

“[T]he 3rd is fond of drinking, and likes all stimulating liquors, therefore goblets and drinking-cups are adorned with representations of this creature; the 4th likes steep and dangerous places, hence gables, towers, and projecting beams of temples and pagodas have carved images of this dragon upon them; the 5th is a great destroyer of living things, fond of killing and bloodshed, therefore swords are decorated with his golden figure.

“[T]he 6th loves learning and delights in literature, hence the covers and title-pages of books and literary works show his picture; the 7th is renowned for its power of hearing; the 8th enjoys sitting, hence the easy chairs are carved in its images; the 9th loves to bear weight, therefore the feet of tables and of hibachi are shaped like his feet.”

– The Mikado’s Empire: A History of Japan from the Age of Gods to the Meiji Era, by William Eliot Griffis, 1876

“The Japanese Dragon (tyatsu) is a slight modification of the Chinese, looking to foreigners like the Old Scratch himself, or a winged crocodile with a tufted snout, and cruel and malicious eyes.

“The dragon forms a familiar object in Japanese decorative art, appearing in the paintings and carvings of temples, dwellings, and tombs; is stamped on the old silver coins; is cut in low and high relief on the native bronze and silver; painted on lacquer, and is woven in the silk brocades, etc.

“It is the emblem of vigilance and strength, and like many of the art motives, originated with the Chinese, to whom it furnishes a comparison of everything that is terrible, imposing, and powerful.

“… As the dragon is the most powerful animal in existence, so the garments of the Mikado are called ‘dragon robes,’ his face the ‘dragon countenance,’ his body the ‘dragon body,’ the ‘ruffling of the dragons scales’ his displeasure, and his anger the ‘dragon’s wrath.’

“The dragon is to the Chinese and Japanese what the griffin was to the early Greeks, and it seems not unreasonable to suppose that the adoption of the one was suggested by the sight of the other.”

– Terry’s Japanese Empire, T. Phillip Terry, 1928

Pingback: “Japan Post” New Year’s promotional postcard (“Nengajou”), c. 1930. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo