War prize German submarines, Yokosuka, c. 1920. Pictured are three of the seven German Unterseeboot brought to Japan as World War I war prize reparations. including two ocean-going, two coastal and three mine-laying U-boats. Also obtained by rights of reparation were plans of the U-Kreuzer, Germany’s large and formidable oceanic cruiser submarines upon which Japan would largely base its own design types built from the mid-1920s onward. The Type J1 I-1 through I-4 submarines, built between 1926 and 1929, were virtual copies of UB-139 and U-142.

See also:

I.J.N. O-5 (former SM UC-99) war prize submarine, c. 1920.

Imperial Japanese Navy Ro-29 class commerce raider submarine, c. 1930.

“The submarine’s onslaught in angry seas.” I.J.N. Submarine Ro-33, c. 1935.

“As part of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s quest to become a modern fighting force, naval leaders decided in May 1904, three months after the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, to experiment with [a] new undersea craft … Japan purchased five Holland-type submarines from the Electric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut. The specially constructed, disassembled sections of these boats and additional materials were shipped by rail to Seattle, Washington, where they were loaded aboard the Kanagawa Maru, which sailed for Japan on 4 November 1904. The submarines were then secretly assembled at Yokosuka Navy Yard.

“… After purchasing the original American Holland-type submarines, the Japanese purchased four additional types from Great Britain, France, and Italy … The Vickers ‘L’ type was the last of Japanese purchases of foreign submarines, but naval analysts gained much insight in modern submarine technology after studying the designs of all these foreign boats. More significant, however, were the German U-boats that Japan, an Allied power in World War I, acquired after the war.

“Japan received seven U-boats as German reparations in 1919; they were studied and tested in preparation for the construction of larger Japanese-built submarines of the ‘I’ class. ‘I’ is a romanization of the first letter in the traditional Japanese syllabary (written as the Greek lambda), ‘RO’ is the second, and ‘HA’ the third. Therefore, under three separate classes established in 1924, an I-boat was a first-line class A submarine, the RO-type submarine was a somewhat small class B boat, and the HA-type Japanese submarine was a small coastal class C boat with a appreciably more limited range and displacement.

“… The technology of German U-boats was clearly superior [to that of other foreign countries … and] the arrival of seven German U-boats offered a special opportunity. Some Japanese believed that they could help redress the naval balance (vis-a-vis the United State and Great Britain] by changing the character of their submarine force for potential use as a powerful arm of the battle fleet.

“… The seven ex-German U-boats were given new names in Japanese navy: the U-125 became O-1, U-46 became O-2, U-55 became O-3, UC-90 became O-4, UC-99 became O-5, UB-125 became O-6, and UB-143 became O-7.

“… The first German submarine specialists had already arrived in Japan [during the summer]. One engineer, who had helped build U-boats at the Germaniawerft in Kiel during the war, was taken to Kure to train [Japanese] officers and men, and to explain the ex-German submarines to the Japanese navy.

“The number of German submarine specialists working for the Japanese reached a high point soon after the war and then tapered off dramatically. Probably several hundred German submarine designers, technicians, and former U-boat officers were brought to Japan under usually five-year contracts — one [U.S.] Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) report originating in Germany claimed that by 1920, ‘over 900 submarine building specialists, etc. have gone to Japan.’

“… Shifting Japanese submarine tactical and strategic thinking helped to create different classifications of boats … Various new tactical and operational concepts about how submarines ought to be used also started to take shape in the navy. However, the dominant view remained unshakable — the chief purpose of the submarine was to intercept the enemy battle fleet and systematically weaken it through repeated attacks.”

– The Japanese Submarine in World War II, by Carl Boyd and Akihiko Yoshida, 1995

- Type U-43 SM U-46

- Type UE II SM U-125

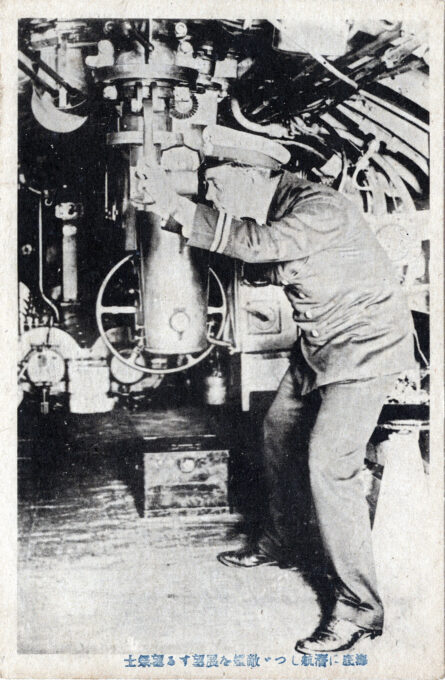

- German Unterseeboot engine room, c. 1920.

- German Unterseeboot torpedo room, c. 1920.

Pingback: Exhibition of war trophy munitions and weapons, Marunouchi, Tokyo, c. 1906. | Old Tokyo