See also:

Tea picking at Uji, c. 1920.

Tea time, c. 1910.

Green tea culture, c. 1950.

“The English word ‘tea’ is derived from the common sound of the character for the plant at Amoy, where it is tay; at Canton and Peking it is cha; at Shanghai, dzo; and at Fuchau, ta. The Japanese, Russians, and Portuguese have retained the word cha (pron. chah); the Spanish is té; and the Italians have both té and cha.”

– Terry’s Japan Empire, by T. Phillip Terry, 1914

“Tea is one of the most important staple products of Japan, and its place in the Empire’s overseas commerce is both old and important. The farmers of Japan find in the cultivation and manufacture of tea a highly remunerative subsidiary occupation, but to the masses of the people it stands for much more than its purely material value. They find therein romance and philosophy, and the aroma of green tea is inseparably interwoven with the daily life of the nation.

“… Its value to them lies largely in the fact that [tea farmers] not only grow the plants but can also complete the manufacture of the product. The report of an expert of the Japanese Tea Manufacturers’ Association stated some time ago that farmers can net from tea ¥50 per tan (0.245 acre) if all conditions are favorable and they manage things properly. This rate of net profit probably is greater than that of any other subsidiary occupation with the single exception of the sericultural industry.

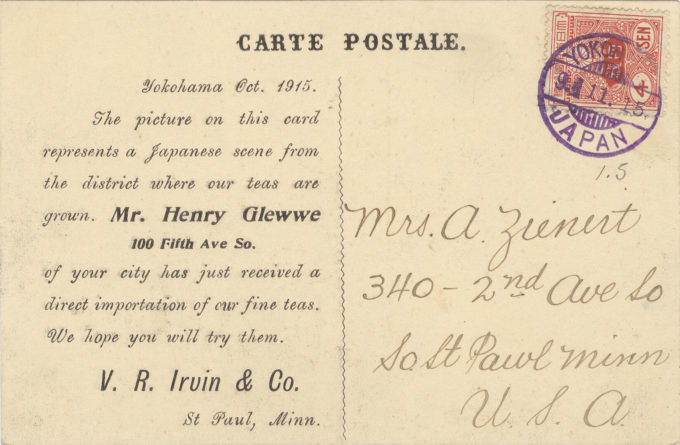

- “Girls getting their tea leaves weight”, c. 1920. (Gift of J. Harper Brady Sr.)

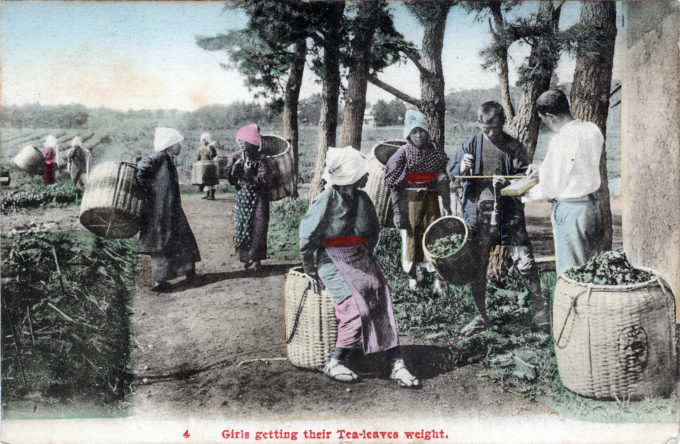

- “Drying tea leaves”, c. 1920. (Gift of J. Harper Brady Sr.)

“… The first picking is made toward the close of April or in the early part of May, when the buds have matured and a few tender leaves are out. Usually young women are employed to pick the leaves by hand. Devices have been invented to save labor in picking, but they have not been widely adopted.

“At Uji no second picking is made, as it is desired to preserve the high quality of the tea. In some provinces around Tokyo two pickings are obtained, and in Shizuoka there are usually three. The second picking is in full swing toward the close of June, and the third takes place early in August. In some districts a fourth crop is harvested, but this practice is not approved by veteran manufacturers.

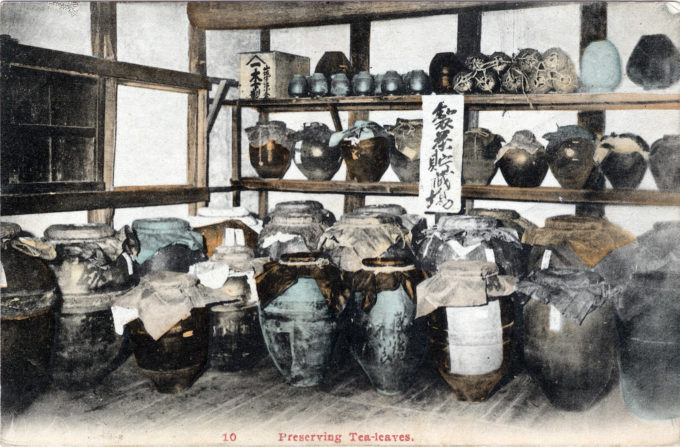

“… Steaming is the first process. This is necessary for preservation of the green color, enhancement of the flavor and softening of the leaves. The second process is firing, which renders the leaves sufficiently dry. In the third and most important process the leaves are rolled into shape and receive the color peculiar to green tea, after which the rolled tea is again fired and placed in tin cans or cases. There are various processes of manufacture, each having its peculiar features and strong points.

- “Selecting & separating tea leaves”, c. 1920. (Gift of J. Harper Brady Sr.)

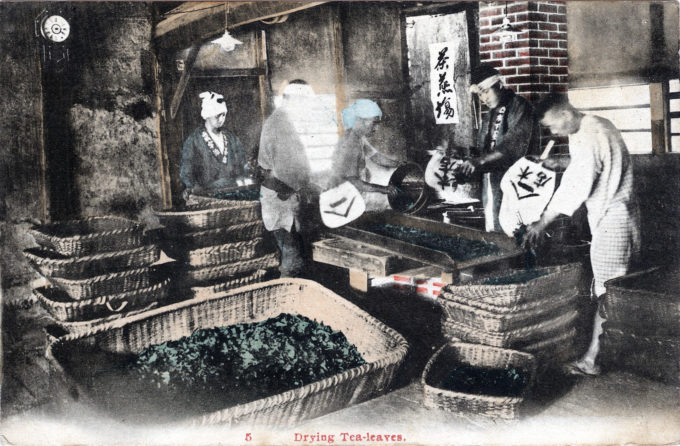

- “Tea tasting”, c. 1920. (Gift of J. Harper Brady Sr.)

“… Though tea culture and manufacture are essentially subsidiary and household industries, in the early days of the Meiji era manufacturers became aware of the advantage of combination and co-operation, and in about 1876 a joint stock company was organized at Shizuoka.

“Since then a number of companies have been established at this place and elsewhere, but in the majority of cases they have confined their operations to the finishing of the leaves for export.”

– Japan’s Tea Industry and Trade, by I. Takano, The Trans-Pacific, January 1920

“Tea, or cha (usually called O-cha, ‘honorable tea’), the national beverage of the Japanese, is believed by them to be necessary to health.

“The tea plant (Camellia theifera, or Thea Sinensis), a shrub 3–6 ft. high, with thin leaves 4–8 in, long, 1 to 2 in. broad and tapering toward both ends; and with small, white, single, slightly fragrant flowers about 14 in. broad, is believed to have existed in Japan from time immemorial, but the peculiar properties of its leaves were not well known until about the 12th cent., when the abbot Myöe, of the Tógano Monastery (Zen sect of Buddhists), near Kyôto, learned (in China, where the tea shrub was cultivated for its refreshing infusion as far back as A.D. 350) of the 9 virtues possessed by the leaf.

“Securing a book of directions for the culture of the plant, and a bag of choice seed, Myöe planted these near Kyôto, whence some were later transplanted at Uji – which ever since has been the chief center of tea-growing in Japan, and where, because of intimate knowledge regarding its cultivation, and the extreme care bestowed upon the preparation of the leaf, some of the finest Japanese teas are produced.

“It was not until a hundred years after Myöe planted his first seed that the tipple came into favor among the upper classes; the fine leaf was then so rare and so highly prized that ‘a small quantity of it, enclosed in a little jar of pottery, used to be given to warriors as a reward for deeds of special prowess, and the fortunate recipients assembled their relatives and friends to partake of the precious gift.’

“Tea did not come into general use among the lower classes until early in the 17th cent., or about the time (1610) when it became generally known in Europe (whither it was brought by the Dutch East India Co., and not by the Jesuits, as is commonly believed).”

– Terry’s Japanese Empire, by T. Phillip Terry, 1914

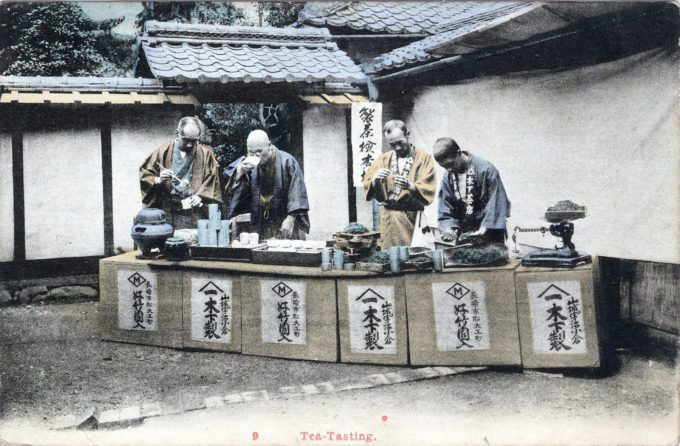

Reverse side of a US Midwestern tea importer’s advertising postcard, 1915. The front image was of tea pickers in Uji, Japan’s top tea-production district responsible (at the time) for 1/3rd of the country’s tea production.

Pingback: “Packing Granger & Co.’s ‘Lion Brand’ packages teas in Japan”, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo