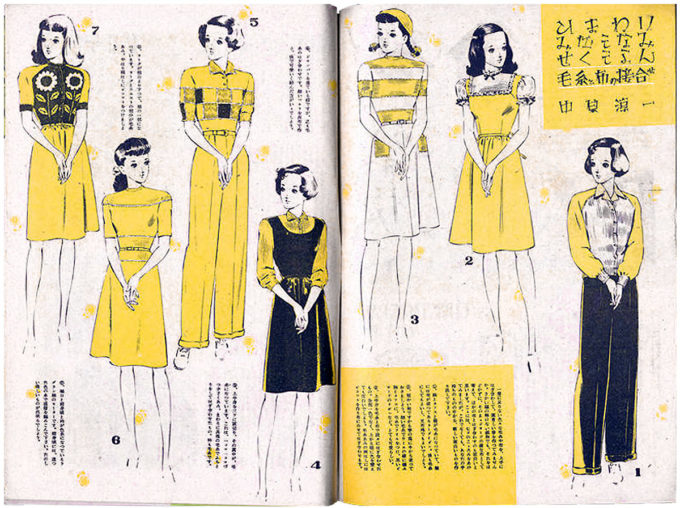

- Nakahara Jun’ichi fashion illustration postcard, c. 1945. The caption reads: “It is a kimono made of various homemade fabrics. Please mix and match plain and patterned fabrics with beautiful colors.”

- Nakahara Jun’ichi fashion illustration postcard, c. 1945. The caption reads: “This jacket can be used as both an air defense suit and an activity suit. When one fabric is in short supply, it is interesting to use a different fabric for the front only, as shown here.”

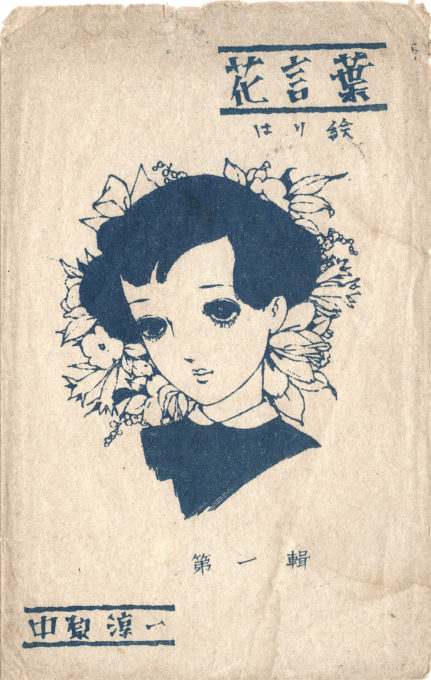

“Nakahara Jun’ichi was a Japanese graphic artist and fashion designer born in Higashikagawa, Kagawa Prefecture, in 1913. He became famous as an illustrator in the 1920s when his work appeared in the magazine Shojo No Tomo [‘Friend of Young Girls’], an early publication (1908) that featured manga-style imagery.

“Despite not being a manga artist himself, Nakahara’s aesthetic style had a huge impact on shojo manga (manga marketed to girls and young women readers). According to the scholar Nozomi Masuda, Nakahara is credited with being one of the key influencers of the characteristic shojo [young woman] style. Nakahara’s hobby of French doll-making, which brought him to Tokyo in 1932 for a solo exhibition at the Ginza Matsuya department store, is said to have strongly influenced his use of oversized eyes in his illustrations, a key element of shojo.

“Popular shojo manga artists from the 1960s and 1970s such as Takahashi Makoto, Hanamura Eiko, and Ikeda Riyoko all credit Nakahara as being the major influence in developing their own artistic styles.

“Nakahara’s influence on the evolution of the Japanese kawaii [cute] aesthetics during the first half of the 20th century cannot be understated. His illustrations not only inspired future manga artists, but his designs and fashions were loved and cherished by many girls and women throughout Japan and helped to elevate the artistic style of girls’ culture and design.

“In addition to his illustration work, Nakahara was also a leading figure in fashion and interior design. Through his magazine publications, dress patterns, and various other goods from stationery to wallpaper featuring his designs, Nakahara was a leading figure in shaping popular ‘girl culture’ in Japan from the 1930s through 1960s.

“In the runup to world war in the late 1930s, interest in Nakahara’s cute, lyrical designs, and fashion goods started to wane and his illustrations, with their western-style large-eyed women, began to catch the attention of government censors. By 1940, his illustrations were no longer allowed to be published. Despite this turn of events, Nakahara continued to actively pursue his passions and that same year, he opened Himawari-ya [‘sunflower store’] in Tokyo selling a variety of goods featuring his designs.

- “Cobbling together” (tsugihagi), Nakahara Jun’ichi illustration postcard, c. 1945. The caption reads: “If you can’t make it up with what you have, buy some new fabric. Make something comfortable by sewing together several pieces of different fabrics in beautiful colors.”

- “Active clothing”, Nakahara Jun’ichi illustration postcard, c. 1945. The caption reads “This [style] is a crisp, active garment. It can be worn all year round by adjusting the blouse. It can be made from an old dress.”

“In August of 1946, less than a year after the war ended, Nakahara published the first issue of his women’s magazine, Soreiyu (trans. Soleil [‘sun’]), followed by Himawari [‘sunflower’], a version for younger women, and, even later, Junior Soreiyu in 1954, a even more junior version of Soleil for young girls.

“Nakahara’s fashion illustrations, in the years immediately the Pacific War when times were hard, resources scarce and dreams were few, encouraged women to aim for ‘beauty in life, in fashion, and in their hearts’ with whatever material was available.

“Nakahara’s style continues to in vogue today and has even gained in popularity in recent years. In 2012, Sou Sou, a popular women’s boutique in Japan released clothing lines featuring Nakahara’s designs such as a stylish yukata (summer kimono) based on his earlier post-war illustrations.

“In the 1950s, Nakahara married Ashihara Kuniko, a Takarazuka Revue star specializing in male roles who would go on to be very active in films and television in the postwar era. In 1989, Ashihara would receive the Order of the Sacred Treasure from Emperor Showa in recognition of her own artistic contributions to Japanese culture.”

Pingback: “Journey”, artwork by Kato Masao, c. 1930. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo