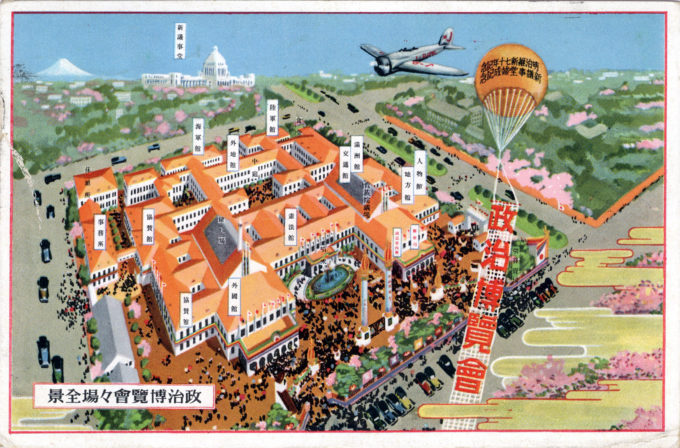

Exposition advertising postcard commemorating the 70th anniversary of the “Meiji Assembly”, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1938. The exposition celebrated not only the Meiji Restoration and the Charter Oath of 1868 (which outlined the main aims and the course of action to be followed toward national modernization) but also the recent completion of the nation’s new parliamentary assembly building, the Imperial Diet. Among the exposition’s sponsors was the Mainichi Shimbun, the country’s largest newspaper, whose courier airplane (J-BANC, a Breda Ba.33) is seen overflying the fairgrounds at Ueno Park with the new Diet Building and Mount Fuji visible in the distance.

See also:

Imperial Diet Building, Kasumigaseki, c. 1890-1940.

“Emperor of Japan”, c. 1905.

“The coup d’etat of January 3, 1868, which abolished the Tokugawa Shogunate and established a new provisional central government in the name of the Emperor Meiji, opened a new era in the political and constitutional history of Japan. The restoration of imperial rule [marked] the beginning of a succession of political, economic, and social reforms that ultimately transformed a decentralized nation of feudal han (kingdoms) into a highly centralized modern capitalist state.

“… By mid-nineteenth century … the Bakufu (Tokugawa military government) feudal political system had deteriorated as economic power had shifted into the hands of the great merchants of Edo and Osaka and the rising merchant-landlord-industrialists (capitalists) of the towns [while] village feudal ruling class of Japan was deeply in debt and faced impoverishment, but even harder hit were the lower-samurai (retainers) – who were forced to accept drastic reductions in their annual stipends – and the peasantry, which were not only burdened by increased taxes but also, in many cases, were at the mercy of the usury of the local capitalists .

“Almost every class or group in society was discontented and was taking measures to protect or improve its position. The Bakufu and many daimyo (feudal lords) strove to control the new capitalist forms of production and wealth; many lower-samurai and ronin (masterless samurai) became convinced that the destruction of the Tokugawa Shogunate was necessary to bring about fundamental changes in society; the peasantry resorted to open rebellion to enforce their demands for improved conditions; and finally, the rising merchant-landlord-industrialist classes bitterly resented the political and economic restrictions imposed upon their operations.

“… The movement to overthrow the Tokugawa Shogunate began in the 1850’s as a series of secret and unconnected plots by samurai who were organized locally around some strong personalitiea such as Yoshida Shoin and Fujita Toko. However, not until the 1860’s was there a gradual integration of these groups into a national revolutionary movement. This was chiefly the accomplishment of discontented samurai and ronin who made their headquarters at Kyoto, where they won the support of many court nobles who had much to gain by the destruction of the Tokugawa Shogunate. While these groups plotted in Kyoto against the Bakufu, their confederates in the han worked to place the military and economic power of their han solidly behind the movement.

“Utilizing the Bakufu’s dilemma in foreign relations and playing upon the jealousy between Satsuma and Choshu, the samurai leaders of the modernization party, who gradually gained ascendancy in their han, blocked the realization of the union plan and established the imperial court as a center of political power; moreover, the foreign bombardments of Kagoshima (by the British Royal Navy) and of Shimonoseki (by a coalition of western powers, including Great Britain and the United States) in 1863-1864 displayed dramatically and convincingly to Satsuma and Choshu that resistance to modernization was suicidal. Finally, after the military impotence of the Bakufu was disclosed in the [failure of the] Second Choshu Expedition of 1866, Satsuma and Choshu openly entered into an anti-Bakufu alliance, which was soon joined by the Tosa, Echizen, and Uwajima clans. This coalition of han, under the leadership of Saigo Takamori, Okubo Toshimichi, and Kido Koin, staged the coup d’etat of January 3, 1868.

“That the new central government was not a new Shogunate can be attributed to the balance of power within the coalition and to the fact that the victory of these samurai in the struggles for power within their han eliminated the possibility of some ambitious, single daimyo trying to seize power.

“… The formal organization of the provisional government established on January 3, 1868, was headed by the Sosai (Supreme Administrator) and included two councils and seven administrative departments. Prince Arisugawa was appointed Sosai, and his deputies (fukusosai) were Iwakura Tomomi and Sanjo Sanetomi, court nobles friendly to the Satsuma and Choshu clans … The whole organization was in reality a great council, the members of which not only formulated policy but administered it through their control of the various departments.”

– The Making of the Meiji Constitution: The Oligarchs and the Constitutional Development of Japan, 1868-1891, by George Beckmann, 1957

Pingback: Transfer of the national capital to Tokyo, 50th Anniversary, 1919. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: Japan-Manchuria Great Industrial Exposition, Toyama Prefecture, 1936. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: 2600th Anniversary Founding of Japan commemorative postcard, Bureau of Crime Prevention, 1940. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo