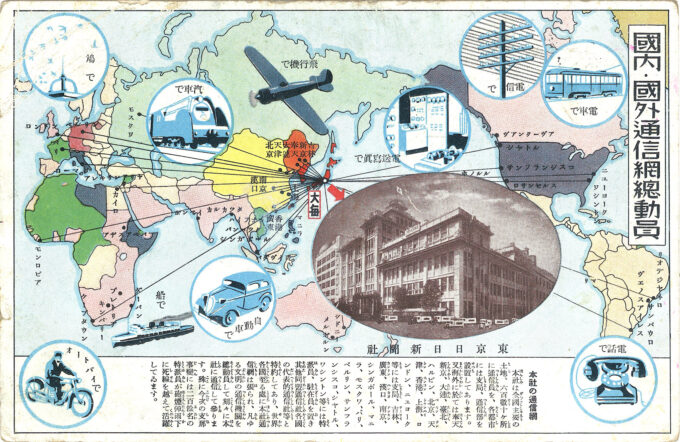

“Domestic and International Communications Network of Correspondents” advertising postcard, Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, Tokyo, c. 1940. “Our company’s communication network extends widely across the world, stationing correspondents in major cities, and we take pride in being the fastest and most accurate news organization.” The map illustrates how the newspaper gathered and transmitted information worldwide through a modern communications network: telegraph, telephone, airplane, ship, railway, wireless photo transmission, and correspondents. Cities across the globe (Moscow, Paris, London, New York, San Francisco, etc.) are marked to show the reach of their reporting.

See also:

Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun (Newspaper), Yurakucho, c. 1930.

“How Newspapers Come to Be”, Tokyo Asashi Shimbun operations postcard series, c. 1935.

The Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, founded in 1872, was part of the Mainichi Newspapers Company, effectively serving as the Tokyo edition of the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun. Together, they operated as a major national daily, rivaling the Asahi Shimbun and the Yomiuri Shimbun.

As with all major Japanese papers during the war years, Nichi Nichi operated under wartime press controls; independent reporting, especially on military defeats or dissent, was eliminated. Instead, as with all other media in Japan, the newspaper emphasized sacrifice, loyalty, and national unity in line with the state ideology (Kokutai). Like the Asahi and Yomiuri, Nichi Nichi leaned on romanticized front-line accounts and government-supplied photographs for content.

In addition, Nichi Nichi Shimbun published sensationalized war reportage, sometimes mixing human-interest drama with patriotic fervor. Among its more notable wartime writers was Yoshimoto Seiji who became known for dramatizing Japanese soldiers, in an easy-to-follow novelistic style, as fearless and selfless. Other “news”, sometimes fictitious, became notorious as wartime propaganda or exaggeration.

Reporters Kazuo Asaumi and Jiro Suzuki wrote “Hundred-Man Killing Contest”, a sensationalized story published in December 1937 during the opening months of Japan’s invasion of China, which detailed a purported competition between two Japanese officers, Second Lieutenants Mukai and Noda, to see who could kill 100 Chinese people with their swords first.

Other notable wartime content was literary and cultural, and was meant for “escape”. For example, a serialized modern Japanese translation of The Tale of Genji was published in 1939, presenting the classical work in contemporary language (as if one were to recite Beowulf using modern English), enhancing its broad, mainstream appeal.

Following the Pacific War, after Japan’s defeat, the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun fully merged with the Osaka Mainichi into the single Mainichi Shimbun, which remains one of Japan’s “big three” national newspapers today.