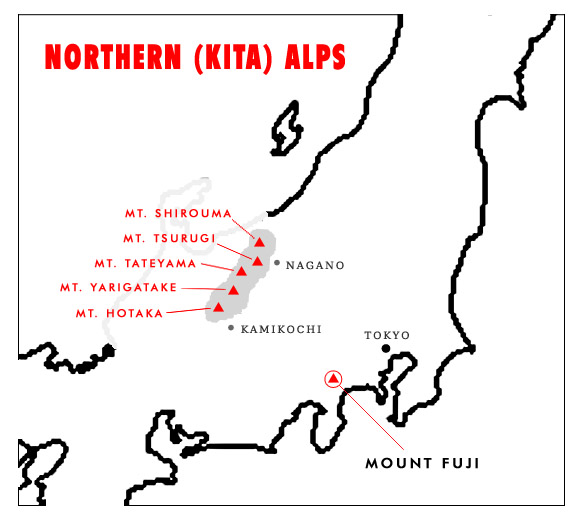

“At Hakuba, the major peaks of Mt. Shirouma, Mt. Shirouma-Yari and Mt. Shakushi rise straight from the narrow valley where the Hakuba Village is located; the linear distance from the [train] station to the trailhead is less than 10 km. Nevertheless, the mountains were not easily approached before the Meiji era modernization of Japan, as snowfields and widespread alpine moors guarded major trailheads.

“However, the situation rapidly changed during the Meiji Peiod, and Hakuba became a favoroured destination for early Japanese alpinists. Some local villagers, such as the young Matsuzawa Teiitsu, saw a business opportunity in the rise of popularity of the mountains among alpinists, reflected in his bold decision to set up a mountain hut in an abandoned army checkpost near the summit in 1906.

“… Walter Weston’s trip to Mt. Shirouma in 1893 became the catalyst for tourism development in the valley and in 1903, the Chuo Line from Tokyo was extended to Matsumoto, easing access.”

– Tourism Development in Japan: Themes, Issues and Challenges, edited by Richard Sharpley & Kumi Kato, 2021

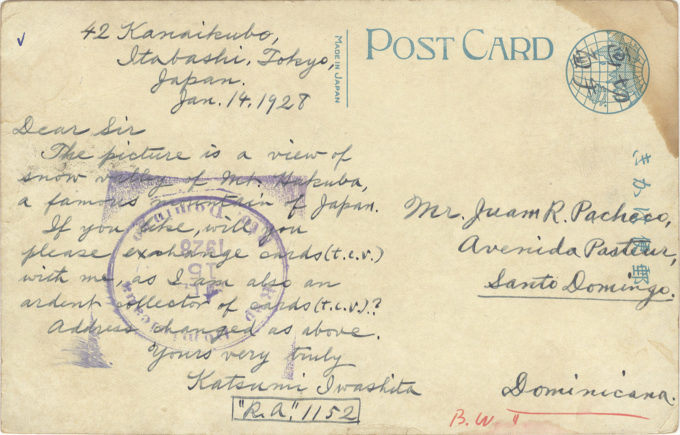

Alpine mountaineering on Mt. Hakuba, Japan Alps, 1928. Foreigners began exploring Japan’s mountains from the 1860s. One, a mountaineering missionary by the name of Walter Weston, suggested the idea of a Japanese alpine club along the lines of the British original, of which he was a proud member. Until then, mountains in Japan were seen as sacred places where divine spirits dwelled, its reaches out of bounds for the commoner except as a sojourn undertaken as a pilgrimage. Sangaku-kai (“Mountain Club”), Asia’s first climbing club, was founded in October 1905 by financier and writer Kojima Usui and six of his friends.

See also:

Tengu-iwa Rock, Rokko-san (Mt. Rokko), Kobe, c. 1930

“Nichiren pointed, ‘Do you see that great peak to the north? It is called Shiro-uma-yama. White Horse Peak.

“In winter it takes on an equine shape, but that is not how it got its name. Early in May, the snows along its slope retreat, leaving what the farmers seem below see as a horse-shaped patch of rock. Each year, when they see this natural seasonal clock, they know, it is time to plant their rice.

“‘Long ago, they gave it the name Mountain of the Paddy Horse. You may not know that shiro has associated with it two kamji. One is ‘paddy field,’ the other ‘white.’

“‘Some clerk somewhere long ago made a mistake, and so we call it by a name it was never meant to have.'”

– Jian, by Eric Van Lustbader, 2017

“A view of snow valley of Mt. Hakuba, a famous mountain of Japan,” postcard reverse, 1928. Credit is often given to William Gowland (1842-1922) for the creation of the term “Japan Alps”. A Meiji-era mining engineer, who came to Osaka from England to work at the Imperial Mint, Gowland roamed through the Japanese back-country in the late 1870s mainly to survey the country’s mineral resources. In one account, published in 1881, he described the pinnacled ridges of central Honshu as something “that might perhaps be termed the Japanese Alps.”

“[F]or the man who really loves mountains, there is something of a similar sensation remnant in his recollections of the hills he has climbed.

“Sometimes the mountain is not much more than that – a happy hill smiling in the sun – mere child’s play so far as height and hardship are concerned. And sometimes it is a majestic mass austerely refusing the ambitious climber the satisfaction of an ascent. Or again, it is a mountain which offers nothing but uneventful peace – an even monotony unbroken by the excitement of wind or storm.

“… There is literally a mountain of benefits to be gained from mountains – however simple the statement may seem on the surface. Mountains are books, music, art to the mind that knows them.”

– “Musings of a Mountaineer”, by Kihachi Ozaki, Travel in Japan, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1941