See also:

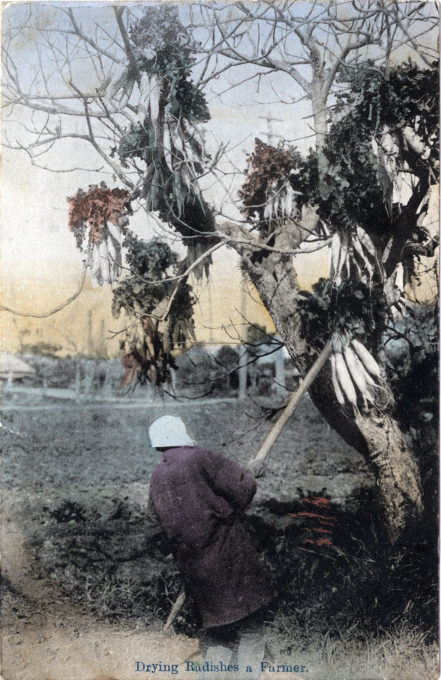

A farm field in the shadow of Mt. Fuji, c. 1920.

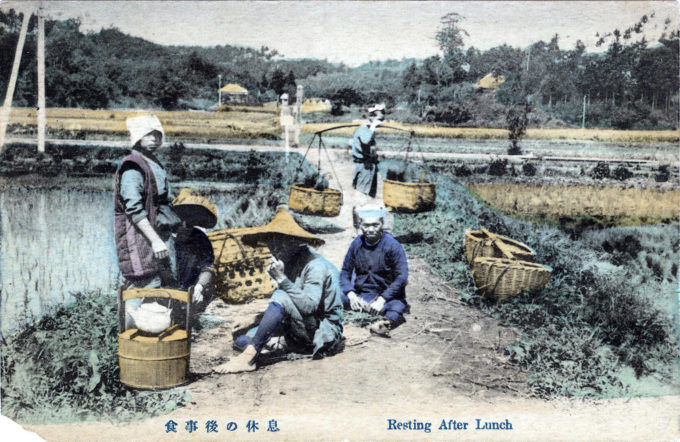

Rice farming, c. 1920.

“Village life – competitive charm”, Nohonshugi (“Agrarian fundamentalism”) propaganda postcard, c. 1940.

“Every few hundred feet , we passed a farm-house screened by clipped hedgerows and bosomed in trees; and at longer intervals we rolled through some village, the country pike becoming for the time the village street. The land was an archipelago of homesteads in a sea of rice.”

– Percival Lowell, “The Soul of the Far East”, 1888

“Works referring to Japan’s rural sector draw a sharp contrast between the Meiji era, 1868-1912 – a time of growth and development – and the 1920s and 1930s, portrayed as decades of stagnation, crises, and impoverishment.

“The latter period is characterized as one of over-population, growing pressure on land, insufficient urban employment for the countryside’s surplus youth, agricultural stagnation, the elimination of rural by-employment, exploitation of peasants by suppliers of agricultural inputs, the collapse of sericulture, and mounting debt, tax, and rent burdens. Did Japanese farmers pass suddenly from a golden to a bleak age?

“… There is a belief encouraged by such expressions as ‘confiscation’ of the ‘produce of the fields’ that imposts on farmers were as a heavy as the 34 percent of the rice crop levied in the early Meiji decades. They were, in fact, far lighter … Although by 1912 all taxes and levies took no more than 12.5 percent of farm income, there was a further reduction so that by 1933 the figure was 6 percent and just prior to World War II, 5 percent.

“From outright exploitation, the government turned, in the 1920s, to assisting farmers. The post-1921 rice-control policy may have encouraged colonial production and failed to stop the price fall before 1932 but it did lift farmer’s returns in 1934-1935 and ensure that during the period from 1931-1938 rice prices were steadier than those of [crops] entirely subject to market forces.

“… Far from being downtrodden, tenants in the 1920s were militant to a degree quite unknown before. Although unions for their protection had started in the 1870s and some 60 existed by 1914, it was from the end of World War I that the number of such groups burgeoned – in 1927 there were 4,582. To secure their goals, they withheld rents, instituted legal proceedings and even resorted to violence against landlords … The movement was never nationwide nor did it repudiate the principle of payment for use of leased land. At its height it embraced fewer than 10 percent of leaseholders.

“Most disturbed by the changes affecting the rural community between 1920 and 1940 were the landlords … Landlords had to fight unions; their control over village government, previously unquestioned, was challenged. Urban capitalists, often with fortunes of recent origin, climbed above them in the national social hierarchy. Nonetheless, because of their nationwide organization, influence in political parties and the Diet, support from ultranationalist groups and military officers of rural origin, landlords were far from being helpless and friendless.

“It was obviously in their interest, however, when lobbying for government aid and subventions to seek to create the impression that conditions had suddenly and radically changed for the worse not only for them but for all farm households … It was the landlords, seeking government aid to shore up their material and social position, and their ultranationalist sometime-allies, intent on securing support for their reactionary aims, who together promoted the notion that from 1920 a permanent crisis and state of impoverishment descended upon the entire farming community.”

– Japan’s Farm Sector, 1920-1940: A Need for Reassessment, by P.K. Hall, Agricultural History, Vol. 58, No. 4, October 1984