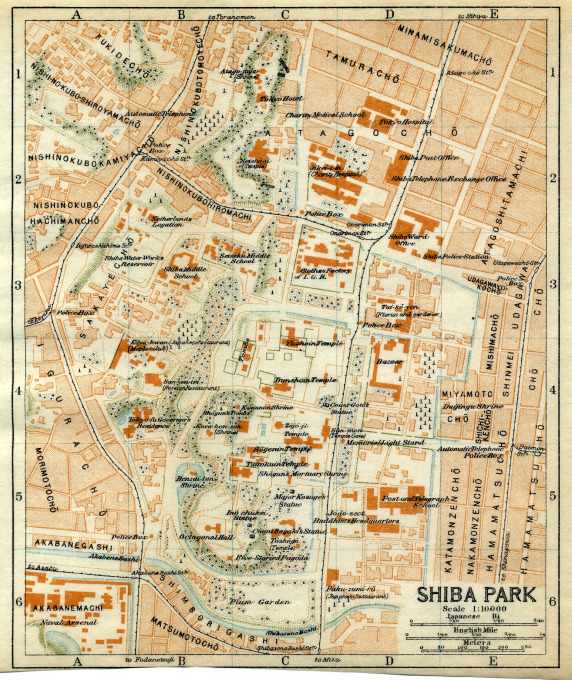

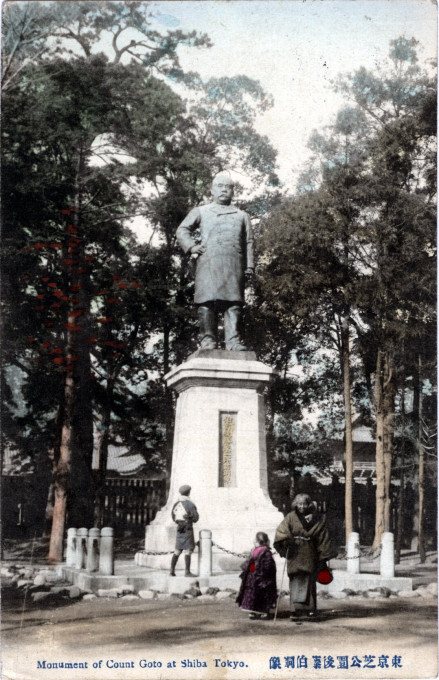

Mounment of Count Goto at Shiba Park, Tokyo, c. 1910. Goto was one of modern Japan’s early political figures. He became a very influential pro-Imperial proponent, exerting great influence on Tosa daimyō Yamauchi Toyoshige to call on shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu to return power peacefully to the Emperor. After the Meiji Restoration, Gotō was appointed to a number of posts, including that of Governor of Osaka. In 1874, he along with three others formed one of Japan’s first political parties (Aikoku Kōtō, ‘Public Party of Patriots’). In 1889, Goto served as Communications Minister; beginning in 1892, he served as the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce under Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi.

“There stands in Tokyo in one of the most beautiful spots of the city a statue of Count Goto. It is of heroic size. The dress chosen is the frock-coat. The pity of it! For the greater part of his life, Count Goto wore the robes of a Samurai. These at any rate would have lent themselves to artistic treatment and I would, if I had the opportunity, very humbly suggest the question whether in the future it would not be well for the Japanese sculptor to discard a costume which in European art is deplored as an unhappy necessity but which here might be so easily avoided.

“In any case and in any dress, we Englishmen are glad that there should be a memorial of this trusty friend. I have already related how when we were attacked at Kyoto on our way to Court in 1868, Goto Shojiro, as he then was, sprang from his horse and killed one of the ruffians who were rushing at Sir Harry Parkes.

“There are few men of that day who would have hailed with greater joy the alliance of his country with England for he was one of the first of the leaders of the new political school to hold out his hand to the strangers from the West, and he remained their consistent friend to the end. Now, alas, he sleeps in the great cemetery of the Aoyama.”

– The Garter Mission to Japan, by Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford & Baron Redesdale, 1906

See also:

The Statue of Saigo at Ueno Park, c. 1910.

Statue of Omura Masujiro at Yasukuni Shrine, Tokyo, c. 1920.

“Count Gotō Shōjirō (1838–1897) was a Japanese samurai and politician during the Bakumatsu (end years of the Tokugamwa bakufu) and early Meiji period of Japanese history. He became a leader of Freedom and People’s Rights Movement which would evolve into a political party. Together with fellow Tosa samurai Sakamoto Ryōma, Gotō was attracted by the radical pro-Imperial Sonnō jōi movement. After being promoted, he essentially seized power within the Tosa Domain’s politics and exerted influence on Tosa daimyō Yamauchi Toyoshige to call on Shōgun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, to return power peacefully to the Emperor.

“After the Meiji Restoration, Gotō was appointed to a number of posts, including that of Governor of Osaka, and sangi (councillor), but later from the Meiji government in 1873 over disagreement with the government’s policy of restraint toward Korea (i.e. the Seikanron debate) and, more generally, in opposition to the Chōshū-Satsuma domination of the new government. Jointly with Itagaki Taisuke, he submitted a memorandum calling for the establishment of a popularly-elected parliament.

“In 1874, together with Itagaki Taisuke, and Etō Shimpei and Soejima Taneomi of Hizen Province, he formed the Aikoku Kōtō (Public Party of Patriots), declaring, ‘We, the thirty millions of people in Japan are all equally endowed with certain definite rights, among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring and possessing property, and obtaining a livelihood and pursuing happiness. These rights are by Nature bestowed upon all men, and, therefore, cannot be taken away by the power of any man.’ This anti-government stance appealed to the discontented remnants of the samurai class and the rural aristocracy (who resented centralized taxation) and peasants (who were discontented with high prices and low wages).

“After the Osaka Conference of 1875, he returned briefly to the government, participating in the Genrō-in. In 1889, Gotō joined the Kuroda administration as Communications Minister, remaining in that post under the first Yamagata cabinet and first Matsukata cabinet. Under the new kazoku peerage system, he was elevated to hakushaku (count).In the second Itō cabinet he became Agriculture and Commerce minister. He was implicated in a scandal involving futures trading, and was forced to retire. After a heart attack, he retired to his summer home in Hakone, Kanagawa, where he died in 1896. His grave is at the Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo.”

– Wikipedia